This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Reagan deploys troops against Sandinistas

US troops during Operation Golden Pheasant

US troops during Operation Golden PheasantOn March 17, 1988, the same day as four defendants in the Iran-Contra scandal were indicted by a US grand jury, the Reagan administration dispatched US airborne and infantry forces into Honduras, north of the Nicaraguan border. In what was termed an “emergency deployment,” the 82nd Airborne Division and the 7th Infantry were sent on a no-notice basis, joining some 3,000 troops already on the ground, moving into position to protect a Contra military leader. Immediately, US forces conducted live-fire exercises and marched to withi n three miles of the Nicaraguan border.

The operation, called “Operation Golden Pheasant,” represented a direct threat of war against the Sandinista government in Nicaragua which had, earlier in the month, sent troops into Honduras to overrun Contra munitions dumps in the San Andrés de Bocay region, where they were staged to supply Contra raids into Nicaragua from north.

Sandinista forces immediately retreated back to Nicaragua and President Daniel Ortega made a national radio broadcast calling on the Nicaraguan people to “be in a state of combat readiness and prepared to repel, resist and defeat any attempted aggression by the United States against Nicaragua.”

The same day in Washington, a US grand jury convened by Special Prosecutor Lawrence Walsh issued indictments against four key Iran-Contra figures: former National Security Adviser John Poindexter, former National Security Council aide Oliver North, retired Maj. Gen. Richard Secord and Iranian arms dealer Albert Hakim.

Twenty-three charges were made, ranging from conspiracy to embezzle millions of dollars to the theft of traveler’s checks. The network of conspirators sold arms to Iran to generate funds for the illegal war against the Sandinista regime in Nicaragua, which had, in 1979, led a revolt to overthrow the longstanding US-backed dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza.

Reagan publicly played down the charges and, 10 days later, pardoned all four defendants.

50 years ago: Baathists visit Cairo after Syria, Iraq coups

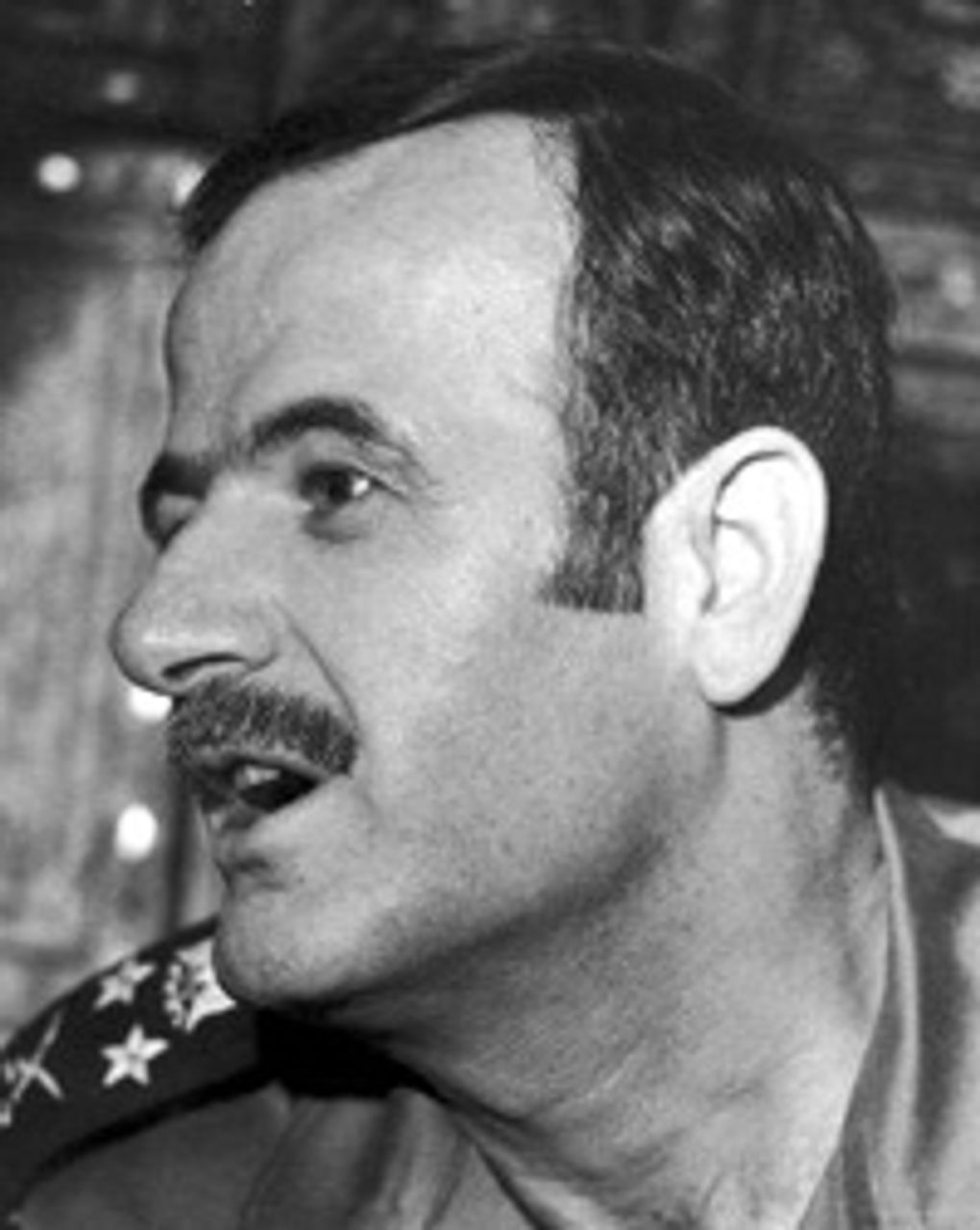

Hafez al Assad in 1970

Hafez al Assad in 1970Delegations of Baathists Party members from Syria and Iraq, fresh from successful military coups in the two Middle Eastern states, arrived in Cairo for “unity” discussions with the Pan-Arabist Egyptian regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser on March 15, 1963. However, no meaningful agreement was reached.

The Syrian coup had taken place on March 8, and the Iraqi coup exactly one month earlier on February 8. The latter, which resulted in the assassination of the nationalist and Soviet Union-backed Prime Minister Qasim, was a clear foreign policy victory for the US, whose Central Intelligence Agency had advance knowledge of the coup and allegedly supplied the Iraqi Baathists with names of Iraqi Communists who were then killed or imprisoned.

The Syrian coup was the third in the country in less than three years, a period of plots and intrigue that, as in Iraq, divided rival factions of the military and the elite—all purportedly nationalist and pan-Arabist—against each other. A leading role in the coup was played by the young Alawite officer Hafez al-Assad, who captured the nation’s most important air force base. As was the case in Iraq, Syrian communists were persecuted in the wake of the coup.

Whatever the stated intent, the Baathists’ pilgrimage to Cairo proved unsuccessful. The United Arab Republic (UAR) of Egypt and Syria had collapsed less than two years earlier with the withdrawal of Syria. In each of the three Arab states, bourgeois factions linked closely to rival economic interests and ethno-religious groupings sought to perpetuate their own interests through the vehicle of the existing state structures and within the borders arbitrarily drawn in the desert by British and French imperialism.

The Arab nationalists bitterly opposed socialism—though in each country they attempted to tap into the broad popularity of socialism by misappropriating the name—and in each case after taking power the Nasserites and Baathists, Pan-Arabists and nationalists repressed the organizations of the working class.

75 years ago: Old Bolsheviks executed at conclusion of third Moscow frame-up trial

Andrei Vyshinsky

Andrei VyshinskyAs the judicial monstrosity of the third Moscow frame-up trial reached its foregone conclusion, 18 of the 21 defendants were executed March 15, 1938, shot to death through the head and neck. Four of the most prominent surviving old Bolsheviks were put to death—Nikolai Bukharin and Alexei Rykov, the former leaders of the Right Opposition, and Nikolai Krestinsky and Arkady Rozengolts, once associated with the Left Opposition.

In the words of Soviet historian Vadim Rogovin, “The third Moscow Trial was a laboratory of the big lie which exceeded in its cynicism and shamelessness all the previous judicial stage adaptations.” The big lie served a political purpose, Rogovin explained: “Many aspects of the third trial can be correctly understood only if one considers that the trial itself was part of a ruthless political struggle in which Stalin was continuously receiving devastating ideological blows from Trotsky.”

Chief prosecutor and one-time right-wing Menshevik Andrei Vyshinsky delivered his closing speech for the prosecution four days before the executions. Spewing lies, calumnies and distortions in his mechanical monotone, his voice only occasionally rising in contrived indignation, Vyshinsky spoke for five hours. Two hours were devoted to consolidating the prosecution case against Bukharin.

Only three of the 21 were spared death: the Old Bolshevik and close comrade of Trotsky, Christian Rakovsky, then 65 years old, D.D. Pletnev and Sergei Bessonov. Bessonov received 25 years in jail, instead of death, because his wholly fabricated evidence implicated the chief but absent defendant, Trotsky. According to Bessonov the co-leader with Lenin of the Russian Revolution was at the center of a hydra-headed plot to kill Stalin, bring down the Soviet Union, and restore capitalism within its borders. All three initially spared were later shot in 1941.

Commenting on the sentences, the Times of London asked incredulously, “If most of the men in high office since Lenin died have been traitors, and the man at the head too simple to suspect it, who has been governing Russia all these years?” The same article mocked the prosecution’s portrait of Trotsky and his “established role as a prince of the outer darkness.”

Trotsky himself followed the proceedings closely and wrote some 20 articles and commentary for the world press on the “Trial of the Twenty-One.” The former leader of the Red Army was moved to ask at one point during proceedings: “A totalitarian regime is the dictatorship of the apparatus. If all the key points of the apparatus are occupied by Trotskyists, who are at my command, why in this case is Stalin in the Kremlin, and I am in exile?”

100 years ago: Mass demonstration against conscription in France

Mass demonstration against French conscription law

Mass demonstration against French conscription lawOn March 16, 1913, a crowd estimated at more than 100,000 people rallied in Pré-Saint-Gervais, just outside Paris, in opposition to militarism, and moves to expand compulsory active military service from two to three years. The demonstration was organized by the CGT, the major trade union organization, the socialist party, or SFIO, and anarcho-syndicalist organizations.

A statement by organizers denounced “the criminal eventuality of war [and] the new military burdens under which they want to crush the country.” It condemned the proposed “Three-years law,” rejected official claims that its purpose was to “consolidate the peace,” and warned that the legislation threatened “to make a military conflict between the German and French people inevitable.”

Fearing that the demonstration could spark a broader movement, the government blocked a trade union demonstration in honor of the Paris Commune from taking place a few days later.

In response to growing popular opposition to the proposed law, Premier Louis Barthou ordered street demonstrations against it to be banned. Conscript soldiers staged a small revolt in May, in opposition to the prospect of additional compulsory service.

A law passed in 1905, at the height of the movement against the military’s anti-Semitic frame-up prosecution of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, reduced compulsory active military service from three years to two. The decision to reinstitute three years of compulsory service, made by the conservative Poincaré after he was installed as president in January 1913, was widely viewed as a response to the expansion of Germany’s military and naval capacities over the preceding year.

The three-years law was passed in May. It continued to be a focal point of opposition to militarism, and was a major issue in the 1914 elections, on the eve of the First World War.