We are posting here an article on the 1934 Minneapolis general truck drivers’ strike, originally published in four parts. It is also available in PDF.

1934: Police use tear gas against unemployed march on City Hall, Minneapolis Minnesota.

1934: Police use tear gas against unemployed march on City Hall, Minneapolis Minnesota.On the morning of February 7, 1934, workers who delivered coal to businesses and residences throughout Minneapolis, Minnesota, fanned out across the city, armed with mimeographed strike instructions and maps, to shut down the 67 companies that supplied the city’s source of heat.

Late in January, the upper-Midwestern city, noted for its fiercely cold winters, had been hit with unseasonably warm weather, and the need for coal had slackened. But on February 1, temperatures suddenly dropped below zero, and the following day the tight-knit group of workers leading the effort to secure improved working conditions, higher wages and union recognition called a meeting. The unorganized coal delivery workers, poverty-stricken and having borne the worst of the Great Depression, voted to strike.

Preparations for this moment had quietly begun three years earlier. Now, within three hours, some 600 workers, comprising truck drivers, their helpers and the workers who labored inside the coal yards, had 65 of the companies shut down. Where individual trucks, aided by police, managed to break through picket lines, strikers used a mobile technique dubbed “cruising pickets” to stop them.

Strikers’ trucks in hot pursuit would have one picket jump on the running board of the offending vehicle and reach inside the cab to pull the emergency brake. A second picket would flip the dump lever on the truck and the load of coal would be deposited in the street.

The strike caught the ruling elite of Minneapolis by surprise. One of their representatives communicated to the Regional Labor Board (RLB), “An emergency exists in this city, whereby the life and safety of the public is menaced and endangered.”

Coal stocks ebbed away, and the city’s police were unable to defeat the strikers. A mere two months earlier, the organization of the Minneapolis capitalists—the Citizens Alliance—had easily disposed of an organizing attempt by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and then smashed a strike at seven furniture manufacturing companies. [1]

The Citizens Alliance had conceded a wage increase, hoping to prevent the coal strike. With the strike on, the RLB stepped in to propose an end on the basis that all strikers be rehired and elections be held to determine representation.

The union accepted the RLB’s proposal and agreed to return to work after three days on the picket lines. It dropped all of its demands save one: that Teamsters Local 574 be the agent representing its members in negotiations with the employers. Implicit in the demand was the acknowledgment that workers who were not members of the union would be free to negotiate for themselves.

For 30 years, the Citizens Alliance had been among the most determined sections of the American ruling class to do battle against the closed or union shop. They upheld the notion of an “open” shop, and peddled the fiction that within this structure individual workers were free to negotiate for themselves with their employers.

And so, the coal dealers signed the RLB proposal and the Citizens Alliance notified its membership that under no conditions would this compel them to sign a contract directly with the union. No challenge to the reign of the open shop in Minneapolis would be brooked.

When the RLB elections were held on February 14, no workers came forward to negotiate independently with the coal dealers. Instead, Local 574 won a smashing victory, with 700 workers voting to have the union represent them.

The decision by the coal dealers and the Citizens Alliance to sign the RLB proposal was seen as a temporary expedient. Coal delivery, being a seasonal operation, would terminate by March or early April. The new pay scale would be a burden to the companies only for a short period. The Citizens Alliance would have plenty of time to determine who had been the leaders of the strike. When deliveries resumed in the fall, these miscreants would be blacklisted, wages rolled back and the open shop secured again.

But the leaders of the coal strike would not wait for the fall. Instead, they rapidly expanded the organizing drive in the trucking industry, leading to an even greater eruption of the class struggle. The titanic events to come in Minneapolis in the summer of 1934 would outstrip, in terms of the independent initiative and mobilization of the working class, any previous struggle of the American proletariat.

The objective foundation of the events of 1934 was the worldwide crisis of the capitalist system, known as the Great Depression. In Minnesota, for the year 1932, operating losses plagued 86 percent of the state’s manufacturers. Between 1929, the year of the Wall Street stock market crash, and 1933, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a bank holiday, 25 percent of the factories in Minneapolis went out of business and the retail value of goods sold dropped 45 percent. In 1932, Minnesota unemployment hit 23.4 percent, a fraction under the national average. The wages of Minneapolis workers fell by 27 percent, and 45 percent of the workforce saw their workweek fall below 40 hours. [2]

1934: Effects of the Great Depression in Minneapolis Minnesota. Unemployed marching on City Hall to demand reinstatement of Civil Works Administration jobs.

1934: Effects of the Great Depression in Minneapolis Minnesota. Unemployed marching on City Hall to demand reinstatement of Civil Works Administration jobs.For workers, the coping mechanism of the era was installment debt, where next year’s wages paid for this year’s necessities. Installment plans would be proffered throughout the 1920s, and when the Depression made it impossible for workers to pay on this debt, the edifice of credit came crashing down. It is estimated that in 1929, 69 percent of the gross national product of the United States was in non-corporate private debt. [3]

The slight upturn in the economy starting in 1933-1934, combined with some New Deal spending, was an impetus for workers to begin to struggle.

But the politically advanced character of the 1934 strike was not merely the outcome of economic processes. The years 1933-1934 saw a marked increase in strikes, but the overwhelming majority ended in defeat.

The high level of class struggle achieved in Minneapolis in 1934 had to do with the historical development of revolutionary Marxist leadership. And this was not purely an American question. Rather, it was bound up with international processes, which at their center involved the principled struggle waged by Leon Trotsky and the Left Opposition against the betrayal of the 1917 Russian Revolution by Stalinism.

Many middle-class “left” commentators and academics are at pains to deny this, and seek to attribute the success of the 1934 Minneapolis truck drivers strike to previous syndicalist traditions in the United States. These elements view the strike leaders as simply good trade unionists, organizers and propagators of trade union militancy.

Even a biographer of Franklin D. Roosevelt insists that their role in the strike had little to do with Marxism. Instead, the leadership “was radical (Trotskyite), tough, fearless, thoroughly honest, and remarkably able, being far more concerned to gain concrete benefits for the workers it represented and far less concerned with ideological purity....” [4]

Why then, on the eve of the Second World War, did the hero of his biography feel compelled to put on trial and imprison these same leaders? He does not give this any consideration.

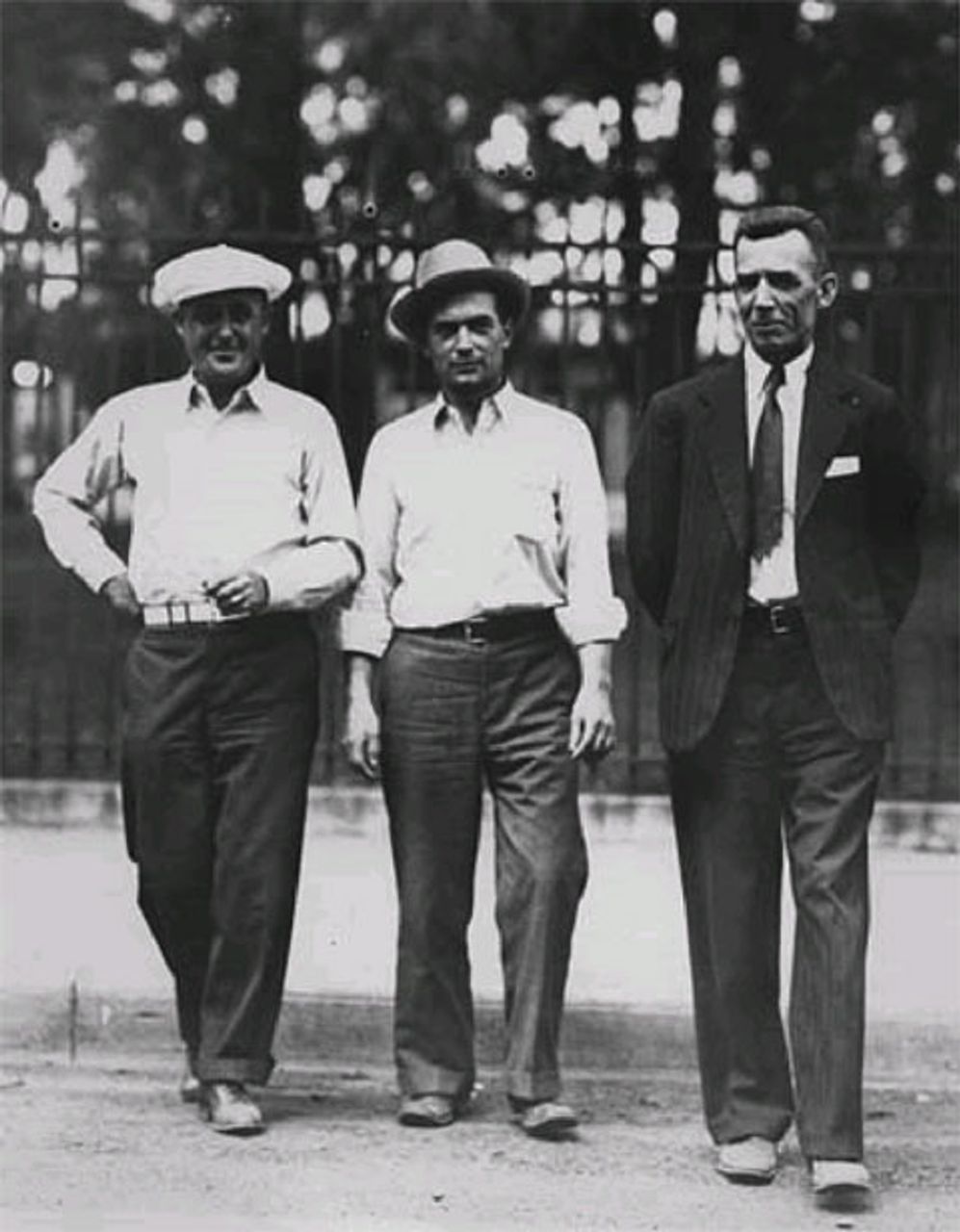

The leaders of Local 574, left to right: Grant Dunne, Bill Brown, Miles Dunne, and Vincent Dunne upon their release from the military stockade in 1934. Far right is Communist League of America lawyer Albert Goldman.

The leaders of Local 574, left to right: Grant Dunne, Bill Brown, Miles Dunne, and Vincent Dunne upon their release from the military stockade in 1934. Far right is Communist League of America lawyer Albert Goldman.It is absolutely true that the coal yard workers at the heart of the struggle—Carl Skoglund and the three Dunne brothers (Vincent, Miles and Grant)—had a wealth of trade union experience in the upper Midwest, including involvement in organizations such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). But this was not sufficient for the events of 1934.

They had an advanced level of political class consciousness and, on this basis, a firm belief in the strength and revolutionary potential of the American working class, because they were members of the American Trotskyist movement, then known as the Communist League of America.

Beyond the difficulties of the organization and day-to-day tasks of the 1934 strikes, and they were enormous, the great challenges that faced these workers centered on confronting the Citizens Alliance and the capitalist state in all its forms: government officials, police, armed deputies, National Guard, labor mediators and the press. A further challenge was countering the strikebreaking of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters bureaucracy and the provocations of the Stalinist Communist Party.

Finally, there was the problem of maintaining the independence of the workers from the Minnesota Farmer Labor Party (FLP) and its governor, Floyd B. Olson. Many “lefts” have portrayed the reformist FLP as an enabling force that facilitated the victory of the truckers’ strike. The reality was quite different. The Trotskyist leaders would again and again warn the workers of Minneapolis they could not rely upon Olson, but instead had to rely upon their independent class strength.

The Citizens Alliance

Minneapolis, situated near the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers, derived its earliest profits starting in the nineteenth century from the state’s timber industry. Saw mills, utilizing river power generated by St. Anthony Falls on the Minneapolis banks of the Mississippi River, later gave way to giant grain elevators, creating the financial fortunes associated with names like Pillsbury. With the addition of railroad baron James J. Hill’s tracks from Minneapolis-St. Paul to the Pacific, the city rose and prospered further by funneling commerce from the northwestern United States through the city’s warehouses, factories and mills.

The city’s millers maintained a monopoly by controlling hundreds of grain elevators throughout the region. Through a local grain exchange, they fleeced farmers from Minnesota and the Dakotas by setting prices and outright cheating in settling accounts. Contracts to supply the cities of the industrial revolution in Britain and Europe made the city the flour-milling capital of the world.

But the growth of capital led to the growth of labor. Between 1901 and 1902, the number of strikes launched by the American Federation of Labor (AFL) doubled. In 1903, a month-long strike rocked the city’s flour mills. The program of the Minnesota State Federation of Labor at that time advocated an eight-hour day, nationalization of utilities, railroads and mines, and “the collective ownership by the people of all means of production and distribution....” [5]

David Parry, president of the National Association of Manufacturers, delivered a speech to a gathering of Minneapolis’s elite in 1903. He declared that the closed shop “is a theory of government to which those who understand and appreciate American liberty and American civilization will never give their willing consent.... I believe that we should endeavor to strike at the root of the matter, and that is to be found in the widespread socialistic sentiment among certain classes of people.” [6]

But Minneapolis’s capitalist class had already started to act. That same year, it formed an umbrella organization called the Citizens Alliance for the express purpose of defeating the closed shop. The Citizens Alliance was the central power. Countless subordinate organizations designated by various acronyms were fostered over the next 30 years to carry out specific aspects of its work.

The Alliance used detective agencies to infiltrate and spy on workers. A centralized employment bureau also kept extensive data on the movement of workers from job to job, and was in a position to help maintain an effective blacklist. In some cases, workers could obtain a job only by agreeing to be an informer. When struggles broke out, private thugs, police, court injunctions and the city and county jail were at their disposal. Extensive funds were made available to companies to weather strikes.

The Alliance also used its economic power to destroy any business that signed a labor agreement. Newspapers that evinced the slightest liberal bias in affairs related to the labor movement found themselves boycotted by advertisers.

Trade schools were set up with the aim not merely of providing craft skills to youths, but as a way of providing an every-ready pool of strikebreakers. Students were inculcated with anti-unionism and respect for management. One of the trade school publications propagandized young trainees, “Your employer is your superior, and more entitled to your respect than you are to his.” [7]

The strikes of 1916

By 1914, there were only four more union shops in Minneapolis than had existed in 1905. Between 1914 and 1916, World War I in Europe enriched Minneapolis businesses, while the city had to deal with a mere three strikes.

But 1916 saw a change. In the northern part of the state, the Industrial Workers of the World led strikes by some 15,000 miners, and thousands of lumberjacks rebelled. The IWW, through its Agricultural Workers Organization affiliate, organized some 20,000 Minnesota farm laborers, who were responsible for bringing in more than 50 percent of the year’s harvest.

In Minneapolis, the machinists’ union came to realize the futility of facing the power of the Citizens Alliance alone when trying to organize one of the city’s largest agricultural implement and munitions manufacturers. Instead, it expanded its strike by temporarily breaking with the craft tradition and organizing every category of worker.

On the heels of the machinists’ strike came a Teamsters organizing drive involving 1,200 transport workers at 150 firms. The Alliance responded with a lockout, while private detectives beat and threatened workers with guns. The Teamsters Joint Council countered with a mass rally and a general strike of all transport workers. The city’s mayor, under orders from the Citizens Alliance, threw the police into the battle to fight and arrest workers.

The use of the police outraged wide layers of the citizenry, and Thomas Van Lear, the Socialist Party candidate for mayor and leader of the machinists’ union, rode this wave to victory. But all of the strikes were ultimately smashed. The Alliance easily sidestepped Van Lear’s “socialist” police chief by using Hennepin County sheriff’s deputies, and the Socialist Party’s reformist program was blocked by the Alliance-dominated city council.

The year 1917

The year 1917 brought two events that profoundly affected Minnesota, as they did the whole country: The Russian Revolution and United States entry into World War I. The coming to power of the Russian workers under the leadership of V. I. Lenin and Leon Trotsky polarized the Socialist Party between its reformist wing and those with a revolutionary outlook, who would ultimately establish the Communist Party.

In Minneapolis, Van Lear was expelled from the Socialist Party, and in his failed 1918 reelection bid, he ran as the candidate of a new party set up by reformist leaders in the Minneapolis Trades and Labor Assembly. Called the Municipal Nonpartisan League, the new party declared itself “for a hundred percent ‘Americanism’ “ and endorsed President Woodrow Wilson’s policies.

The Citizens Alliance took advantage of the wartime political climate to escalate its assault on labor and other opponents by setting up the Minnesota Commission of Public Safety (MCPS). Its orientation was indicated by a business publication, which declared, “When stress of war comes, such government mechanism must of necessity become more or less autocratic.”

A Citizens Alliance member who was an architect of the MCPS stated, “Treason will not be talked on the streets of this city, and the street corner orators, who denounce the government, advocate revolution, denounce the army and advise against enlistments, will be looking through the barred fences of an internment camp out on the prairie somewhere.” [8]

Civil liberties were suspended. The MCPS, in acts of intimidation, jailed or removed from office those who opposed the war. Rallies were banned. The headquarters and newspapers of union and farm groups were raided or shut down. Hundreds of agents carried out tens of thousands of investigations, night raids and arrests.

1917: Civilian Auxiliary, led by “men of means”.

1917: Civilian Auxiliary, led by “men of means”.The state established the Minnesota Home Guard—11 battalions led by “men of means” and under control of the governor—to be used against workers and demonstrations. The Citizens Alliance took the opportunity to organize the Minneapolis Civilian Auxiliary, a paramilitary militia. When a streetcar strike hit both Minneapolis and St. Paul in 1917, the Home Guard and Civilian Auxiliary were mobilized to defeat the strikers.

Postwar period and emergence of the Farmer-Labor Party

In the postwar period, the Citizens Alliance sought more energetically to project itself across the entire state of Minnesota and foster groups similar to itself in other cities. This bolstered its efforts to get legislation passed by the state legislature.

In the postwar strike wave, the Alliance was not only determined to hold the line against the closed shop, but to go onto the offensive and roll back the past gains of the AFL by destroying craft jurisdictions, including those of the building trades. Soon, two thirds of the construction projects in St. Paul were non-union. The Alliance pushed for injunctions that didn’t merely limit picketing during strikes, but entirely banned it.

Many of Minnesota’s workers and farmers, looking back on the period of wartime terror and other experiences, were well aware that the Commission of Public Safety was a bipartisan affair, staffed equally by both Democrats and Republicans.

Oppositional politics in Minnesota featured a new movement called the Nonpartisan League (NPL). The NPL originated in North Dakota, where the Socialist Party found a response to its agitation among a significant section of farmers, who believed they were being cheated by the railroads, grain exchanges, milling companies and banks.

The party set up a “non-party” or nonpartisan status for these farmers. In a state where rural constituents constituted three quarters of the population, this faction of the party grew rapidly and rivaled the “orthodox” faction.

The SP, fearing this growth, dropped the non-party dues payers. But the organization refused to die and continued on under the name Nonpartisan League, with a reformist program that aimed to set up state-owned elevators and establish a rural credit system to help farmers. Its tactic was to enter candidates into the Republican Party’s primary. The result was a 1916 landslide victory in the state House, and in 1918 the Nonpartisan League took over the Senate.

The NPL movement spread to Minnesota, where it found a ready reception among many farmers. But Minnesota was more diverse. While farmers constituted an important section of the population, the NPL could not be successful ignoring the urban working class of Minneapolis, St. Paul and Duluth, as well as Iron Range miners and workers spread out across the state in industries such as timber. This led the AFL to set up its own nonpartisan organization and collaborate with the NPL.

The Republicans, however, were not about to allow the NPL to take over its party, as the NPL had in North Dakota. Ultimately, the NPL and AFL were compelled to run their candidates in the 1920 elections under the Farmer-Labor label, where they made a good showing. In 1922 and 1923, respectively, they captured both of the state’s seats in the US Senate. But the Citizens Alliance and the Republicans continued to dominate state politics. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party’s share of the vote in the 1922 election shrank to 10 percent, having been displaced by the Farmer-Labor Party (FLP).

The FLP, while commanding a loyal following among the two constituencies in its name, was in essence a reformist party shot through with middle-class elements, who became its directors and office holders (Floyd B. Olson, FLP governor in 1930, was formerly a Hennepin County prosecutor, who first attempted to enter politics as a Democrat; Elmer Benson, who became the second FLP governor, following Olson, was a rural banker).

Starting around 1923, some trade union leaders such as reformist Socialist Party member William Mahoney thought that participation by members of the Communist Party could strengthen their hand in the Farmer-Labor Party. Others, such as Robley Cramer, editor of the Minneapolis AFL’s Labor Review, maintained the following attitude toward the CP: “They are not very numerous, they are good workers, and a splendid dynamic force.... They can help a great deal if they are with you, and they can make a lot of trouble if you keep them out.” [9]

But the Communist Party pursued disastrously opportunist policies in relation to the Farmer-Labor Party. It did not understand the necessity of the working class playing the dominant role, as fought for by the Bolshevik Party in the October 1917 Revolution, where the peasantry was mobilized behind the working class in the establishment of a workers’ state. It would not be until 1928 before the issue was clarified for some in the CP. The alliance between AFL and SP elements with the CP would be short-lived, as the reformists came under sharper and more severe attacks from the conservative wing in the FLP, with the final rupture leading to the expulsion of the CP.

The leaders of Minneapolis Teamsters Local 574

Vincent R. Dunne (left) and Carl Skoglund

Vincent R. Dunne (left) and Carl SkoglundIn 1915, Vincent Dunne met Carl Skoglund in Minneapolis. Skoglund, a Swedish immigrant, had joined the Socialist Party in 1914. Dunne had been a member of the IWW, and Skoglund introduced him to Marxism. They would both rally to the Russian Revolution and later join the Communist Party. They had both passed through many of the great struggles of their time in Minnesota.

In 1924, they met James P. Cannon, a leading member of the Communist Party, who was passing through Minnesota on one of his tours for the International Labor Defense. Impressed with Cannon, they approached him four years later, in 1928. Both were deeply troubled by the expulsion of Leon Trotsky and Gregory Zinoviev from the Russian Communist Party. Cannon, also troubled, could only reply, “Who am I to condemn the leaders of the Russian revolution.” [10]

1922: Max Eastman, James P. Cannon and William Haywood in Moscow

1922: Max Eastman, James P. Cannon and William Haywood in MoscowLater that year, Cannon traveled to the Soviet Union for the Sixth World Congress of the Communist International. It was there he obtained Leon Trotsky’s document “The Draft Program of the Communist International: A Criticism of Fundamentals.”

The document laid bare the anti-Marxist orientation of the Stalin-Bukharin faction, which failed to proceed from the international contradictions of capitalism and falsely believed that socialism could be constructed within the boundaries of the Soviet Union. Trotsky maintained that only on the basis of an international perspective and world revolution could the Soviet Union be defended and advance towards socialism.

The document in a number of places revealed how the Stalin faction had subordinated the working class in China, Britain and other countries to non-proletarian forces. In an extended section, the document derided the opportunist policies pushed by the Stalin faction in relation to farmer-labor parties in the United States, where farmers were advanced as an independent revolutionary force. Trotsky insisted that oppressed sections of the middle class could not play an independent revolutionary role and had to be led by the working class armed with a Marxist program.

Cannon returned to New York and immediately set about to organize an opposition within the Communist Party of the United States based on Trotsky’s perspective. Within a short period of time, he and his adherents were expelled by his opponents in the American CP for their support of Trotskyism. The CP then issued directives that other branches and districts of the Communist Party blindly endorse the expulsion of Cannon.

In Minneapolis, both Carl Skoglund and Vincent Dunne were expelled from the CP when they balked on voting for the expulsion, and instead asked for more information. Both had personal experience with expulsions, having been turned out of the AFL in 1926 during the bureaucracy’s “Red Purge.” Dunne, who had been a candidate for the Farmer-Labor Party, was also expelled from that organization earlier in 1928. In the end, more than two dozen Minneapolis CP members were expelled and a majority joined the opposition after becoming familiar with Trotsky’s program.

The Cannon group ultimately established the Left Opposition in the United States under the name Communist League of America (CLA). During this period, the followers of Trotsky were seeking to win the Communist parties back to a Marxist and internationalist perspective in a struggle against the Stalinist leadership. This period was rich in theoretical development for the CLA.

“They spent a good deal of time studying the Marxist classics and discussing how to shape their revolutionary course,” related Farrell Dobbs, who would join the CLA in the lead-up to the 1934 strike. [11]

Craft unionism versus industrial unionism

A major impediment to the movement of the working class was the AFL bureaucracy. The growth and changes in the structure of capitalism, principally the qualitative development in the division of labor brought on by the assembly line, made the AFL policy of dividing workers in plants into separate crafts reactionary.

Teamsters International President Daniel Tobin personified the right-wing conservative craft bureaucrat. In 1934, his hatred for the Trotskyist leaders of Local 574 boiled over when they brought truckers’ helpers and warehouse, or “inside,” workers into the local union fold. Tobin considered unskilled or non-driver workers “rubbish.” As the upsurge of the workers in 1933 began, Tobin stated, “The scramble for admittance to the union is on...we do not want the men today if they are going on strike tomorrow.” [12]

In 1934, the Trotskyists did not hold any official positions within Local 574. Bill Brown, the president of the local, was an exception to the typical bureaucrat. He welcomed the collaboration of the Trotskyists.

But the majority of the officials in the union followed Tobin. The union membership in the coal yards on the eve of the strike was a mere 75 workers, and these members were the result of a backroom deal with a small group of coal dealers, who agreed to the closed shop in return for the union drumming up business for them among residential customers. The union officials were satisfied with this state of affairs and not inclined to organize other workers.

Prelude to 1934

In 1930, Floyd B. Olson was elected as the first Farmer-Labor governor of Minnesota. During his campaign, he had set up “All-Party Committees for Olson” in an effort to obtain support from sections of the Democrats and Republicans. Upon taking office, patronage was handed out to those who had supported him.

1931: Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party Governor Floyd B. Olson

1931: Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party Governor Floyd B. OlsonOne of the first struggles that rocked the Midwest was the 1932-1933 strike by the National Farm Holiday Association. Between 1920 and 1930, farm prices had fallen. Gross annual farm income dropped from $15.4 billion to $9.3 billion, and some 450,000 full owners lost their farms. The value of farm property dropped $20 billion and tenancy increased by 200,000. [13]

1932: National Farm Holiday Strike; Farmers picket roads into the Twin Cities to bar the transfer of farm products.

1932: National Farm Holiday Strike; Farmers picket roads into the Twin Cities to bar the transfer of farm products.The farm strike involved tens of thousands of farmers. Highways and railroad tracks into cities with major farm markets in Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota and Minnesota were blockaded to bar the movement of farm produce in the hopes of creating scarcity and raising prices. Strikers halted farm foreclosures. Pitched battles with sheriff’s deputies took place, and some farmers were shot.

It is quite possible that truck drivers hauling farm produce into Minneapolis in 1932 had their loads dumped by angry farmers and remembered these tactics when they took to the streets in 1934. In the event, the National Farm Holiday Association became one of the big financial backers of the strike by Local 574, providing both money and food donations.

In Austin, Minnesota, some 90 miles south of Minneapolis, a young packinghouse worker named John Winkels joined the picket lines of farmers and helped stifle any movement of farm produce into the local market. Later, in 1933, Winkels led an occupation of the George A. Hormel & Company hog slaughtering facility.

Olson mobilized the National Guard and dispatched them toward Austin. Winkels and his fellow workers responded by sandbagging the entrance to the plant. “We went and got shotguns, rifles, pistols, sling shots, bullets, whatever we could get a hold of,” said Winkels. “We even got an old machine gun. We told the people we were ready for them—let them come.” [14]

1933: Strike at Hormel Packing Plant, Austin.

1933: Strike at Hormel Packing Plant, Austin.Olson was able to defuse the struggle in Austin and get a settlement and union recognition. It was, however, one thing for the Farmer-Labor governor to cajole an isolated capitalist in rural Minnesota into compromise. It was quite another to reconcile the Citizens Alliance with mobilized strikers in Minneapolis.

The proliferation of farm and labor struggles caused Olson to move away from the conservatism of the early days of his administration. In 1933, he attempted to push through the legislature an unemployment insurance program.

The Citizens Alliance lashed out against the legislation as the “ultimate socialistic control of life and industry.” Olson attempted to reason with the opposition. He warned, “Industry, as such, being concerned largely with the sole motive of profit, has concerned itself little with the welfare of its workers.... It now remains for the state to do what industries failed to do.... This proposal is an attempt, whether wisely or not, to patch up the so called capitalist system—to prevent the substitution of socialization of industry.... If employers are not willing to take such steps, then inevitably some other system will have to be substituted.” [15]

May 1934

After the success of the February coal strike, the Trotskyists did not sit on their victory. They made a decision to expand beyond the coal yards and organize all workers across the transport industry, from drivers and their helpers, to dock or platform workers, to laborers inside the warehouses. They issued a leaflet that put forward two points to workers:

“DO YOU KNOW? That under Section 7-A of the N.I.R.A. workers are not only granted the right to organize, but are guaranteed the right to exercise this privilege without discrimination?

“DO YOU KNOW? That the coal drivers of Minneapolis took advantage of this privilege to organize and through our organization gained a 25 percent wage increase?”

This sparked widespread interest among workers, who came knocking on Local 574’s door. The union moved quickly to flood the local with new members before Tobin, situated in Indianapolis, Indiana, could sabotage the operation.

Workers who had been laid off from the coal yards were also mobilized as organizers and given training as speakers to accelerate the campaign. The discussions with workers led to special meetings, the formalization of contract demands and a better understanding of the industry as a whole.

On April 15, the union went public with the results of its campaign by organizing a mass rally at a downtown theatre. More than 3,000 workers attended and signed up to join the union. A decision was made to take advantage of Governor Olson’s popularity, and more importantly to put him on record as supporting the strike, by inviting him to address the rally. Olson did not attend, but sent a subordinate to read a letter on his behalf. In part, it stated, “It is my counsel, if you wish to accept it, that you should follow the sensible course and band together for your own protection and welfare.” [16]

The union rented a giant garage that would serve as a central headquarters for the strike. A kitchen was set up to feed the strikers. A hospital staffed with volunteer nurses and a doctor was installed, making clear to everyone that the leadership had no illusions that the struggle could be won without a fight. Mechanics were recruited to maintain the fleet of 450 vehicles that would be used to dispatch pickets during the strike.

All members of the Communist League branch in Minneapolis were drawn into the preparations for the coming strike. They spearheaded the organization of the city’s 30,000 unemployed so as to neutralize the possibility of their being used as strikebreakers, and drew the best elements of them into the ranks of the strikers.

Women’s Auxiliary serving pickets at strike headquarters commissary

Women’s Auxiliary serving pickets at strike headquarters commissaryThey also organized a woman’s auxiliary, drawing in the wives of strikers and supporters to provide clerical support and staff the hospital and kitchen. At the height of the strike, some 10,000 workers and their families ate in the commissary in a single day. The auxiliary played a critical role as the strike dragged on, leading demonstrations of up to 700 women on city hall, pressuring landlords to back off from evicting strikers who fell behind on rent, and picketing offices of the capitalist press to protest lies and falsifications that aided the employers.

The strike force was divided into units, and the most able workers were designated as picket captains. Special squads composed of the best fighting elements of the union were held in reserve, so as to be ready for dispatch at critical moments. Motorcycle couriers provided contact across the far-flung field of struggle, and car patrols swept through neighborhoods looking for scab trucks and notifying strike headquarters.

The strike begins

Union contract demands were rejected by the trucking companies, and on March 15, Local 574 voted unanimously to strike the following day.

In the opening days, cruising pickets shut down trucking, while more and more transport and inside workers joined the union, swelling its ranks to 6,000. Police were active, arresting some 169 workers in the first four days. Fines were as high as $50 per worker, and some were sentenced to the workhouse for 10-45 days.

The Minneapolis Tribune warned on the fifth day of the strike: “The city’s food supply began to feel the pinch of the strike...a general shutdown of bakeries is estimated to be only a day away. In groceries, similar conditions existed....” [17]

Police moving trucks against unarmed pickets

Police moving trucks against unarmed picketsOn May 19, large numbers of police were organized to protect the movement of trucks. Strikers, using only their bare hands, engaged in some of the first serious fighting. Later that evening, a company spy who had worked his way into the union strike headquarters was able to dispatch three truckloads of pickets to a pre-arranged location where police and Citizen Alliance deputies were waiting. He managed to convince a group of women to accompany the strikers.

When the pickets arrived the trap was sprung and all were beaten mercilessly. Carl Skoglund described the scene: “I remember the night. They brought the women in, and the other pickets from the Tribune Alley, and laid them down in rows in strike headquarters. All the women were mutilated and covered with blood, two or three with broken legs; several stayed unconscious for hours. Saps and night clubs had been used on both the men and women.” [18]

In past struggles, such use of violence by police and thugs had cowed workers. This time, the incident ignited the ranks of strikers, who quickly armed themselves with every sort of club they could muster. The stage was set for the colossal battles of May 21 and 22 that would go down in history under the name “Deputies Run.”

On the one side, hundreds of police and Citizens Alliance deputies, primarily businessmen, congregated in the market. The cost of deputies for the Citizens Alliance in the May strike would run from $75,000 to $100,000.

The union deployed some 500 pickets and kept 900 workers at strike headquarters in reserve. Throughout the night, another 600 strikers had secretly infiltrated by groups of three into the AFL headquarters next to the warehouse district. With the first movement of trucks, the secreted union forces burst out and the melee begin. As the battle raged, deputies took flight, leaving the police to absorb the full onslaught, and some 30 had to be hospitalized.

The following day, Minneapolis Police Chief Michael Johannes called on the American Legion to provide 1,500 recruits and scoured the jails for potential thugs who could be enlisted. Additional deputies were provided by the Citizens Alliance.

On the other side, members of the building trades and electrical workers came out in sympathy strike and joined the army of Local 574. Some 20,000 to 30,000 people, including spectators, packed the downtown market district waiting for the fight to begin. A local radio station set up portable equipment to provide a blow-by-blow account of the fight. Again, the first movement of produce detonated the battle.

Historian William Millikan has pieced together an account of the day culled from reports submitted by deputies of the Citizen Alliance:

“Following their battle plan, several thousand angry pickets retreated south on First Avenue to Seventh Street, where they wheeled and marched west toward the railroad tracks. Reinforced by three truckloads of armed strikers, the force met a small police line stretched across the corner at Seventh Street and Third Avenue between the Weisound Malt & Beer Company and the Minneapolis Anoka & Cuyuna Range Railroad passenger depot.

“While the 23 police officers briefly stalled the march, the special deputies posted on the northeast corner of the intersection were advised to flee into the market. Leaderless and outnumbered fifty-to-one, the businessmen quickly retreated from the battleground. One deputy overheard a well-dressed striker comment, ‘We are getting the rats down in the hole where we want them.’

May 21: Strikers go into action against Citizens Alliance deputies

May 21: Strikers go into action against Citizens Alliance deputies“Three squads watched nervously from the alley in front of the Gamble-Robinson Company as the mob ‘broke loose and came down Third Avenue like a bunch of hyenas.’ As the pickets rushed down Third Avenue at a run, the special deputies retreated into their alley. Within minutes, shouts of ‘here they come’ were heard from in front of Ryan Potato Company on Third and Sixth Street. CA [Citizens Alliance] Director Arthur Lyman yelled to several squads and led them forward to defend the corner. As the crowd swept down Third Avenue, ‘they appeared to be beyond any sense of reason and were certainly one hundred percent in a wild rage.’ The real battle for control of the Minneapolis market district was about to begin.

“A mass of several thousand angry strikers poured into Sixth Street in the next ten minutes, filling the street and even covering the awning roof on the market side of the street. The CA’s army retreated under an aerial bombardment of bricks, bottles, fruit boxes, sticks, two-by-fours, and steel rods. Deputies, cut or bleeding or unconscious, were dragged off the street as the strikers overtook the retreating army.

Street fighting in warehouse district

Street fighting in warehouse district“In vicious hand-to-hand fighting, more deputies were clubbed to the ground by hoses, lead pipes, baseball bats, and iron hooks. When an injured deputy still displayed his badge, he was clubbed unconscious. Bloodied deputies crawled or were dragged into the buildings lining Sixth Street or rolled under vehicles in a desperate attempt to escape the ferocity of the strikers. One deputy realized that the truck drivers ‘took a terrible grievance towards us and were angered beyond mad men.’

“As the strikers bore down on them, one of the deputies shouted above the din at nearby police officers: ‘For God’s sake get your gun out. They are going to kill us!’...

May 21: Worker takes down a Citizens Alliance deputy

May 21: Worker takes down a Citizens Alliance deputy“As the CA’s army retreated down Sixth Street, Arthur Lyman, vice president of the American Ball Company and a CA director, rallied twenty deputies to help the men in the front lines escape. ‘Give the poor chaps a chance,’ he called. Within minutes, Lyman was trapped in the frenzy of swinging clubs. A small, sickly-looking man in dirty coveralls struck him on the head. Dazed, Lyman was thrown over an automobile and worked over with clubs and fists. His unconscious body dropped to the street by the alley, lying there until an improvised ambulance could pick him up...

“Isolated, without any leadership, vastly outnumbered, and viciously outfought by the strikers, the demoralized deputies broke ranks and ran to protect themselves.” [19]

Both police and deputies disappeared from the district and pickets took up positions directing traffic. It was a complete rout. The event electrified workers across the country.

“Newsreels, which were then a feature of motion picture entertainment, showed combat scenes filmed during the Tuesday battle. Workers everywhere reacted enthusiastically to the news. Audiences in movie houses broke out in cheers at the sight of pickets clubbing cops for a change, since in most strikes it was entirely the other way around.” [20]

The significance of the battles of May 21-22, considered alongside other major strikes by autoworkers in Toledo, Ohio, and longshoremen in San Francisco, was summed up by James P. Cannon:

20,000 to 30,000 people pack the warehouse district

20,000 to 30,000 people pack the warehouse district“The messianic faith in the Roosevelt administration which characterized the strike movement of a year ago and which, to a certain extent, provided the initial impulse for the movement, has largely disappeared and given place to skeptical distrust.... [T]he striking workers now depend primarily on their own organization and fighting capacity and expect little or nothing from the source to which, a short year ago, they looked for everything.... What has actually taken place has been a heavy shift in emphasis from faith in the NRA [Roosevelt’s National Recovery Act] to reliance on their own strength.” [21]

AFL officials in Minneapolis were especially nervous about these developments. They did not want the strike to be resolved by the independent movement of the workers, but rather to fall under the control of Governor Olson. They met with city officials in an effort to end the street fighting and bring in the Farmer-Labor governor. Republican Mayor A.G. Bainbridge requested that Olson mobilize the National Guard, which he did, although the units were kept just outside the city at this point. Local 574 immediately denounced the calling up of the guard and organized a mass rally of the city’s workers.

A tempestuous series of negotiations was begun that ultimately compelled 166 companies to recognize the union and accept the return to work of all workers, including those the employers wanted to victimize for “crimes” during the strike. Seniority was also recognized, and some ambiguous language was inserted concerning the recognition of inside workers. Future wages, however, were left to arbitration.

Nevertheless, the strike leaders believed that the agreement constituted a basis from which future gains could be registered and recommended the membership accept. On May 31, the agreement was signed and workers soon returned to their jobs.

Up until this point, Cannon and the leadership of the Communist League in New York had provided backing to the strike by phone contact. But Cannon recognized in the situation the necessity of throwing the whole party behind the struggle in Minneapolis. He came out to Minneapolis, followed soon after by other key members of the party, to expand the political and practical organization of the struggle. Among those who went to Minneapolis were Max Shachtman and party lawyer Albert Goldman.

Within two weeks of the settlement, the Citizens Alliance recovered its balance and began to work toward undoing the victory of the workers in the May strike. Arbitration on future wage increases broke down and negations over the inclusion of inside workers in the union were frustrated.

Governor Olson, having earlier committed himself to support the inclusion of inside workers, backtracked and said it would have to be arbitrated. The Regional Labor Board backed the Citizens Alliance and denied the union representation of the inside workers.

Employers shorted workers on wage increases won back in the February settlement, and individual workers were fired. Seniority was violated. Some workers were given wage increases in the hopes of further dividing the ranks. In all, Local 574 recorded 700 grievances over the course of a relatively short period. Preparations began for a new strike.

The strike of July-August

On July 5, a massive parade and rally was staged by the union to prepare workers for the coming struggle. AFL leaders and FLP office holders were also invited and put on record as supporting the next strike.

The May events had swung wide sections of the population behind Local 574. One aspect of this would lead to a considerable inflow of intelligence bearing on the activities of the Citizens Alliance and the employers. Secretaries listened in on their bosses’ phone calls and created carbon copies of critical letters or communications. Janitors retrieved letters from wastebaskets. All of this was forwarded to strike headquarters for analysis.

Local 574 cruising pickets stop a driver to check for permits.

Local 574 cruising pickets stop a driver to check for permits.During the May strike, some problems had flared up between pickets and individual farmers who attempted to bring their produce into the city. The union rectified this by getting farm groups such as the National Farm Holiday Association to organize and staff pickets on the main roads entering the city. Only farmers who were members of farm organizations would be allowed to enter the city, and a special farmers’ market was set up outside the market district to allow them to sell their produce. The membership rolls of the farm organizations began to swell and dues were paid up.

The most important addition to the union cause was the daily strike paper, The Organizer, which combated the lies of the Citizens Alliance and capitalist press and the treachery of the mediators, the labor bureaucracy and the Farmer-Labor government, and focused the workers’ movement on its most critical tasks. Cannon considered it the “crowning achievement” of the strike. “Without The Organizer the strike would not have been won,” he wrote. [22]

The Citizens Alliance also prepared. Charles Rumford Walker wrote: “Chief of Police Johannes asked for a nearly 100 percent increase in his police budget. The budget included the cost of 400 additional men and the maintenance of a police school.... He asked for $7,500 for the school and $33,200 for other equipment. ‘The police,’ he said, ‘must be trained just like an army to handle riots.’ Included in the budget were $1,000 worth of machine guns, 800 rifles with bayonets, 800 steel helmets, 800 riot clubs, and 26 additional motorcycles.” [23]

In May, the Citizens Alliance had focused a good deal of its propaganda against the closed shop, while the union merely demanded what the federal government had already legislated as the workers’ right—to organize and select their own representation. The tactic made the employers appear obstinate in the eyes of wide layers of the public.

The Alliance now focused much more narrowly on the communist leadership of Local 574, hoping to confuse the uninformed worker and pressure the AFL bureaucracy to undermine the struggle. In the Minneapolis Star, the CA asked, “Are the Communists insidiously taking over the union labor organizations—most of which are reputable and patriotic—to achieve the Russianizing of Americans?” [24]

Teamster International president Tobin aided the Alliance by issuing a public attack on Local 574 in the union’s magazine. “We see from the newspapers that the infamous Dunn[e] Brothers...were very prominent in the strike of Local No. 574 of Minneapolis.... All we can say to our people is to beware of these wolves in sheep clothing...the International Union will help you in every way it can...to protect our people from these serpents in human form.” [25]

An article in The Organizer, approved by the rank and file, responded:

“We note with the greatest indignation that D. J. Tobin, president of our international organization, has associated himself with this diabolical game of the bosses by publishing a slanderous attack on our leadership in the official magazine. The fact that this attack has become part of the ‘ammunition’ of the bosses in their campaign to wreck our union is enough for any intelligent worker to estimate it for what it really is. We say plainly to D. J. Tobin: ‘If you can’t act like a union man and help us, instead of helping the bosses, then at least have the decency to stand aside and let us fight our battle alone.... Our leadership and guidance has come from our own local leaders, and them alone. We put our confidence in them and will not support any attack on them under any circumstances.’ ” [26]

The Trotskyist leaders of the strike continued to hold no positions within the union. However, to counteract the threat from the conservative local Teamster officials, workers elected a “Committee of 100” of the best elements in the union. The turbulence of the coming struggle meant that rapid decisions would have to be made without the possibility of convening the full membership. The conservative executive board of the union was then incorporated into the strike committee, where it could be controlled and outvoted.

The leaders of Local 574 also faced provocations from the Stalinized Communist Party. In 1934, the CP internationally was still carrying out its ultra-left policy, known as the “Third Period.” This policy had met with its most disastrous results in Germany, where the CP leadership, under directions from Stalin, denounced the Social Democrats as “social fascists,” rejecting Trotsky’s call for the party to adopt the tactic of the united front and appeal to the Social Democratic Party and unions to join with the CP in defending workers’ organizations against Hitler and his Nazi brownshirts. The Stalinist ultra-left policy, essentially the reverse side of the opportunist coin, repelled the Social Democratic workers, left the reformist labor bureaucracy off the hook, widened divisions within the working class, and paved the way for Hitler’s assumption of power in January 1933.

In the United States, the CP called for the construction of separate “red” trade unions and opposed a political struggle to expose and remove the right-wing leadership of the AFL. In Minneapolis, it tried to set up a rival unemployed workers’ union in opposition to the one already sponsored by Local 574 and the AFL.

Some of the CP’s more bizarre tactics included disrupting the activities of Local 574 picket captains, who were trying to stop scab trucks, and instead demand that they occupy city hall. The Stalinists also issued a proclamation demanding that CP members be put on Local 574’s negotiating committee. In relation to the farmers, it declared the National Farm Holiday Association a social fascist movement.

During the May strike, the CP revealed its inability to advance correct Marxist tactics in relation to the Farmer-Labor Party and Governor Olson. It demanded that Local 574 call a general strike directly against Olson. This was at a time when Olson was verbally—not to mention financially, having personally contributed $500 to Local 574—supporting the strike. The overwhelming majority of workers harbored illusions that he would aid the struggle of Local 574. The Trotskyist leaders judged correctly that his “support” would have to be tested and exposed in the course of the struggle before workers could shed their illusions in the FLP governor.

While the workers did indeed change their evaluation of Olson in the heat of the July-August struggles, the Stalinists soon dropped their social fascist rhetoric and moved in the opposite direction. When the Kremlin inaugurated the popular front line in 1935, which called for the subordination of the working class to the liberal bourgeoisie, the CP flip-flopped and supported the FLP in Minnesota as well as Roosevelt and the Democratic Party nationally.

Police use tear gas

Police use tear gasOn July 16, a new strike was launched and cruising pickets hit the streets of Minneapolis. Strikers began the strike without the clubs they had used to conclude the May strike. It was an effort to deny the police an excuse to initiate violence or provide Governor Olson with a pretext to bring in the National Guard. Mayor Bainbridge, nevertheless, called on Olson to mobilize the Guard, and the FLP governor initiated a recall of the units and set up a provisional battalion at the Minneapolis Armory.

Mediators dispatched by the Roosevelt administration met with both sides, but the Citizens Alliance refused to sign a direct contract with the union. On the evening of July 18, the Alliance met with Police Chief Johannes and pressured him to act. A plan was hatched to launch a direct and violent attack on the union, with the hope of shattering the strike. The Minneapolis Star quoted the chief giving orders on July 19 to his assembled officers:

“We’re going to start moving goods.... Don’t take a beating.... You have shotguns and you know how to use them. When we are finished with this convoy there will be other goods to move.... Now get going and do your duty.” [27]

The union avoided that day’s provocation. But the following day, July 20, a single truck carrying a few groceries pulled out from the loading docks in the market district. Some 100 police in squad cars armed with riot guns, accompanied by another 50 police on foot, escorted the vehicle. When a truck with nine pickets moved to cut it off, police leveled their riot guns and opened fire.

Bloody Friday, July 20. Police open fire on pickets; Local 574 striker Henry Ness and unemployed worker John Belor are killed.

Bloody Friday, July 20. Police open fire on pickets; Local 574 striker Henry Ness and unemployed worker John Belor are killed.“In a matter of seconds two of the pickets lay motionless on the floor of the bullet-riddled truck. Other wounded either fell to the street, or tried to crawl out of the death trap as the shooting continued. From all quarters strikers rushed toward the truck to help them, advancing into the gunfire with the courage of lions. Many were felled by police as they stopped to pick up their injured comrades. By this time the cops had gone berserk. They were shooting in all directions, hitting most of their victims in the back as they tried to escape, and often clubbing the wounded after they fell.” [28]

In all, 50 pickets and another 17 bystanders were wounded. One Local 574 striker, Henry Ness, and an unemployed worker, John Belor, died. The Organizer denounced Johannes and the Citizens Alliance, writing: “You thought you would shoot Local 574 into oblivion. But you only succeeded in making 574 a battle cry on the lips of every self-respecting working man and working woman in Minneapolis.” [29]

That night, 15,000 workers rallied at strike headquarters. On July 23, a citywide strike of all transport workers was launched. More than a dozen members of the Minneapolis Central Council of Workers, which represented unemployed workers assigned to Roosevelt New Deal work projects, had been shot in the ambush, and all 5,000 members of the council walked off the job.

100,000 attend funeral of Local 574 martyr Henry Ness

100,000 attend funeral of Local 574 martyr Henry NessOn July 24, some 100,000 people lined the streets and took part in a mass march that accompanied Henry Ness’s body through Minneapolis. Police disappeared from the streets and strikers assumed responsibility for directing traffic.

The anger of workers as well as sections of the middle class ran thick. Calls came for the firing of the police chief and the impeachment of the mayor. Many workers came to the union headquarters armed with guns. But the strike leaders understood that to allow the arming of the workers would play into the Citizens Alliance’s hands.

The Minneapolis strike, despite nationwide popular support, still remained a largely isolated movement. To unleash civil war would provide the pretext for both Olson and Roosevelt to militarily crush the strike. The goal of the struggle continued to be union recognition and a contract. The Trotskyist leadership, in what strike leader Farrell Dobbs confessed was “the hardest thing I ever did in my life,” disarmed the workers. [30]

As the strike resumed, Police Chief Johannes used 40 squad cars with riot police to accompany slow-moving convoys of trucks. At the same time, masses of unarmed cruising pickets shadowed these convoys. While some produce was delivered, Johannes did not have the forces to provide coverage to all 166 companies.

An extremely complex situation developed. FLP Governor Olson faced fall elections and realized that his inability to end the strike could undermine his future. As one historian put it, the “strike reinforced moderates’ understanding of third-party vulnerability and the continued advantages, indeed the necessity, of working with a national Democratic administration.” [31]

Roosevelt calculated that he could use the favor of federal collaboration in ending the strike to bring the Farmer-Labor Party more securely under the wing of the Democratic Party. James Cannon later explained the attitude of the Communist League of America to Olson:

“The strike presented Floyd Olson, Farmer-Labor governor, with a hard nut to crack. We understood the contradictions he was in. He was, on the one hand, supposedly a representative of the workers; on the other hand, he was governor of a bourgeois state, afraid of public opinion and afraid of the employers. He was caught in a squeeze between his obligations to do something, or appear to do something, for the workers and his fear of letting the strike get out of bounds. Our policy was to exploit these contradictions, to demand things of him because he was labor’s governor, to take everything we could get and holler every day for more. On the other hand, we criticized and attacked him for every false move and never made the slightest concession to the theory that strikers should rely on his advice.” [32]

Meeting with Roosevelt’s mediators, Olson fashioned an agreement that called for the reinstatement of all strikers, union elections, minimum wages and arbitration to determine future wages. On the question of inside workers, the agreement limited this expanded representation to only 22 companies. The proposal was publicly announced, and Olson threatened martial law if the two sides did not agree. By threatening martial law, the governor hoped to encourage individual firms to break ranks with the Citizens Alliance and sign. Only those firms that signed on would be given military permits to move products.

Despite their opposition to arbitration and the limited representation of inside workers under the proposal, Local 574’s leaders saw in the offer a basis for securing future gains. By winning elections in those firms where inside workers had been excluded under the mediator’s proposal, they would still be able to claim the right to negotiate on their behalf. A recommendation was made to the ranks to accept the proposal and it passed overwhelmingly. The Citizens Alliance replied, “Under the circumstances we cannot deal with this communistic leadership,” and rejected the proposal. [33]

On July 26, Olson declared martial law and 4,000 guardsmen invaded downtown Minneapolis. Picketing was banned as well as open-air rallies. CLA leaders Cannon and Max Shachtman were arrested within hours, held, and then ordered out of town. They agreed to exile, but then ensconced themselves in St. Paul, where they continued to provide guidance to the strike.

National Guardsmen deployed in Minneapolis

National Guardsmen deployed in MinneapolisInitially, only small firms signed on to the mediators’ proposal, while large firms remained committed to Citizens Alliance discipline. Under intense pressure, Olson began to cave in on his original plan, and within four days more than 7,500 trucks had been given permits, including those from firms that had rejected the mediator’s proposal. Olson, in an attempt to extract an agreement from the Alliance, further backtracked on the demand that employers recognize the union.

On July 31, Local 574 held a rally that was attended by 25,000 workers. Olson was roundly denounced, and the union declared that picketing would be resumed the following day in defiance of martial law.

Vincent R. Dunne arrested August 1 during National Guard raid on Local 574 strike headquarters

Vincent R. Dunne arrested August 1 during National Guard raid on Local 574 strike headquartersAt 4 a.m. on August 1, some 1,000 National Guardsmen surrounded the union headquarters and shut it down. Vincent and Miles Dunne, along with Bill Brown and the union’s doctor, were put in a military stockade. Wounded workers in the union’s hospital were hauled off to a military institution. Olson also had the guard raid the headquarters of the AFL.

Grant Dunne and Farrell Dobbs escaped the dragnet and met with members of the Committee of 100. A decision was made to decentralize the union’s operations across the city. The leadership of the strike now fell to the lower ranks, but little was lost. The back streets of Minneapolis were enveloped in a virtual guerrilla war out of the sight of the National Guard and police.

“A series of control points was set up around the town, mainly in friendly filling stations, which cruising squads could enter and leave without attracting attention. Pay phones in the stations and couriers scouting the neighborhoods were used to report scab trucks to picket dispatchers. Cruising squads were then sent to the reported locations to do the necessary and get away in a hurry. Trucks operating with military permits were soon being put out of commission throughout the city.

National Guard protecting strikebreaker

National Guard protecting strikebreaker“Within a few hours over 500 calls for help were reported to have come into the military headquarters. Troops in squad cars responded to the calls, usually to find scabs who had been worked over, but no pickets.” [34]

An attempt by Governor Olson to pressure picket captains to enter into negotiations to settle the strike failed miserably. The pickets responded by demanding the release of their leaders. Meanwhile, The Organizer came off the press with headlines:

“Answer Military Tyranny by a General Protest Strike!—Olson and State Troops Have Shown Their Colors!—Union Men Show Yours!—Our Headquarters Have Been Raided! Our Leaders Jailed! 574 Fights On!”

National Guard raids AFL Central Labor headquarters

National Guard raids AFL Central Labor headquartersIn the May strike, the Stalinists of the Communist Party had agitated for a general strike. But the Trotskyists had avoided the demand and instead limited wider strike calls only to transport workers under their control. They understood that a general strike was not a panacea for the workers’ movement. The calling of a general strike would have allowed the AFL bureaucrats to take seats on a general strike committee, from which they would become a majority that would give its support to any settlement manufactured by Olson at the expense of the workers.

In August, however, Olson was completely discredited as a strikebreaker, and the call for a general strike ignited a movement of workers across the city on behalf of Local 574 and prevented the AFL from undermining the struggle. In the new situation, Olson was compelled to back down, release those he had arrested and return strike headquarters to union control.

On August 5, Olson revoked all military trucking permits save those for a limited number of goods. The Citizens Alliance raged and demanded that military law be suspended. The following day Olson appeared opposite the Alliance’s attorney in front of the Hennepin County District Court to decide the issue. The court backed Olson’s control of the guard and permits, declaring, “Military rule is preferable under almost any circumstances to mob rule.” [35]

After martial law, a virtual guerrilla war enveloped the back streets of Minneapolis.

After martial law, a virtual guerrilla war enveloped the back streets of Minneapolis.It is believed that behind the Citizens Alliance request for a suspension of martial law was its desire to clear the way for an escalation of indiscriminate shooting of workers in the streets. Father Francis Haas, one of Roosevelt’s mediators in the thick of the Minneapolis events, wrote to a friend, “I dread to think of the violence and bloodshed to follow.” [36]

Local 574 was faced with grave difficulties throughout August. The cost to maintain the union’s operations was $1,000 a day. Its leading ranks were exhausted, and 130 members had been arrested by the National Guard and put in the stockade.

Local Teamsters bureaucrats attempted to undermine the strike by demanding that taxi drivers and filling station attendants be detached from Local 574 and put in separate crafts. Some workers, discouraged by the arduous struggle, drifted back to work. But the union continued to receive support from the working class and it shouldered on. It was also aware of problems in the opposing camp.

On August 8, Olson left Minneapolis for a private meeting with President Roosevelt, who was visiting the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Olson appealed to Roosevelt to use the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to put pressure on the Minneapolis companies, and primarily Northwest Bancorporation.

Northwest Bancorporation “had the greatest concentration of banking resources of any region of the country outside of California.” It was the central pillar of the Alliance, using its credit to support businesses that toed the open shop line and to punish those inclined to settle with unions. But the Depression had found sections of the mighty bank’s empire unable to meet the New Deal’s requirement that its capital fund exceed 10 percent of its deposits. In 1933, the bank had been forced to get the RFC to purchase $23 million in preferred stock and capital notes to keep the bank from going under. [37]

Roosevelt’s negotiators now threatened to recall the loan as a way of bringing the Citizens Alliance into line, while trying to defuse the explosive class tensions in Minneapolis.

The strike had also added to the fiscal woes of the ruling class. The July-August strike would ultimately last 36 days and, according to author Thomas Blantz, “cost the city an estimated $50,000,000. Bank clearings during the strike were down $3,000,000 a day, approximately $5,000,000 was lost in wages and the maintenance of the National Guard had cost the taxpayers over $300,000.” [38]

The intelligence networks of Local 574 gave them an insight into the disarray within the ranks of the employers, and The Organizer pounded away:

“Various sources, including direct statements of individual employers themselves, indicate a widespread revolt during recent days in the ranks of the firms affected by the strike. The staggering financial losses incurred as a result of the strike already far exceed what the cost of the modest wage increases demanded by the union would amount to over a long period of time....

“The financial Hitlers who want to smash every labor union in town...have confronted these firms with the alternative of a ruination of their business...

“The most fatal illusion that could seize us now would be the idea that the new military orders of Governor Olson, limiting truck permits, can win the strike for us and that we can passively rely on such aid. It was Olson and his military force that started the truck movement in the first place. There is no guarantee that he will not turn about and do the same tomorrow.... There is no power upon which we can rely except the independent power of the union. Trust in that, and that only.” [39]

Local 574 president William Brown, Miles Dunne and Vincent R. Dunne after their release from the military stockade at the fairgrounds

Local 574 president William Brown, Miles Dunne and Vincent R. Dunne after their release from the military stockade at the fairgroundsOlson did indeed begin to backtrack on granting permits, and soon thousands of trucks were rolling, of which only one third had agreed to the mediated proposal. But on August 18, the Citizens Alliance cracked and agreed to a proposal for new mediation.

The new proposal was similar to the previous one in terms of union elections, the representation of inside workers, and a ban on victimizations. Minimum wages were set at 50 cents an hour for drivers and 40 cents an hour for other workers.

The elections resulted in Local 574 winning representation rights for 61 percent of the workers in transportation. In arbitration, wage rates were increased by 2-1/2 cents an hour for all workers. In the second year of the contract, wages were raised again by another 2-1/2 cents.

In local union elections, the conservative elements of the union were voted out and Vincent and Grant Dunne, along with Farrell Dobbs, were installed.

Aftermath

The smoke had barely cleared from the victory in Minneapolis when Miles Dunne was dispatched to Fargo, North Dakota, where a struggle for unionization and better wages flared into a violent confrontation. Strikes also broke out in Minneapolis and spread to St. Paul when 2,000 auto mechanics in both cities launched a unified struggle. In every case, workers called upon the leaders of Local 574 for help and emulated their tactics.

In November 1934, Local 574 called a meeting of left-wing trade unionists that established the Northwest Labor Unity Conference. It incorporated into its program principles such as solidarity and reciprocal aid among locals, industrial unionism, organization of the unemployed under the trade unions, education, establishment of a labor defense organization and opposition to policies of class-collaboration. It also established a newspaper called the Northwest Organizer, which continued the role played earlier by The Organizer.

The American ruling class was not oblivious to the dangers to its class interests posed by these developments. The intervention of Roosevelt in the 1934 strike had nothing to do with aiding the workers. He intervened in an effort to keep the movement of the working class within the parameters of the capitalist system and block the development of socialist consciousness.

The AFL bureaucracy, which had either stood to the side or hindered the movement of 1934, roused itself to organize workers only from the same perspective as Roosevelt and at his behest. At the 1935 AFL convention, International Typographical Union President Charles P. Howard attempted to persuade his fellow bureaucrats that they had to attempt to organize unorganized workers precisely in order to defend the capitalist system:

“Now, let us say to you that the workers of this country are going to organize, and if they are not permitted to organize under the banner of the American Federation of Labor they are going organize under some other leadership.... I submit to you that it would be a far more serious problem for our government, for the people of the country and for the American Federation of Labor itself than if our organization policies should be so molded that we can organize them and bring them under the leadership of this organization.” [40]

At the convention, the AFL split over this question, and the emergence of the Committee for Industrial Organization initiated the campaign to bring the inevitable outbreak of industrial struggles under reformist, rather than revolutionary, control.

The struggle expands

1935: Pickets and striking workers at the Strutwear Knitting Company, Minneapolis.

1935: Pickets and striking workers at the Strutwear Knitting Company, Minneapolis. 1935: Police at Strutwear Knitting Company strike, Minneapolis.

1935: Police at Strutwear Knitting Company strike, Minneapolis.The outreach of Local 574 to unions and workers sympathetic to it proved critical in the coming two years, as the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) nationally, and the Minneapolis Central Labor Union and Teamsters Joint Council locally, launched a concerted effort to destroy the Trotskyist leadership of Teamsters Local 574. In April 1935, IBT President Daniel Tobin revoked the charter for Local 574 and dispatched thugs to bring the trucking membership under a new local and a leadership loyal to him.

That same year, Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party (FLP) candidate Thomas Latimer was elected mayor of Minneapolis. Latimer, however, proved to be a bitter enemy of the workers. Within one month of taking office, he joined police on the picket line to help escort scabs against a Machinists’ strike. Later, police under his command shot and killed two workers and wounded several more. In another strike, IBT Local 574 leader Vincent Dunne was seized by police, beaten, thrown into jail, and denied medical treatment for cracked ribs.

In 1936, the violence increased as Latimer, on behalf of the AFL bureaucracy and the Citizens Alliance, gave Tobin’s pistol- and blackjack-toting goons a green light to beat up Local 574 members and did nothing when they unleashed a particularly bloody attack on Vincent Dunne and Local 574 Vice President George Frosig.

But Local 574 persevered, as workers in Minneapolis and throughout the state rallied to its defense and continued organizing. Further, the local received support from a minority coalition of 15 AFL unions in the Minneapolis Central Labor Union.

Crowd outside of meeting at Teamsters Local 544 at the corner of Third Street North and Plymouth North, Minneapolis (circa 1936).

Crowd outside of meeting at Teamsters Local 544 at the corner of Third Street North and Plymouth North, Minneapolis (circa 1936).By the end of 1936, the entire transport industry in Minneapolis was 100 percent unionized. Four of Tobin’s agents who had been sent to spearhead the destruction of Local 574 ended their goon attacks and brokered a compromise, whereby they joined forces with the Trotskyists under a new union charter, designated as Local 544. Tobin was compelled to relent for the moment, and the Northwest Organizer became the official organ of the regional Teamsters Joint Council, under the editorship of the Trotskyists. Tobin’s policy of craft unionism was replaced by industrial organization.

The surrender and defection of old-style officials might seem unusual today. And it was certainly the exception. But it was the product of careful tactics employed by the Trotskyists. Every step by Tobin’s agents was exposed in the Northwest Organizer, and workers played the decisive role in defeating the campaign against the Trotskyist leadership.

Farrell Dobbs explained that Tobin’s point man in the assault “expected us to face him, staff against staff, sap against sap, gun against gun. He also assumed that the union ranks would be little more than spectators, waiting to see who would emerge the winner and proceed to lord it over them.... It didn’t take long for Murphy to become disabused of these notions.” [41]

Among the four Teamster officials who defected, L.A. Murphy, who was from the Chicago Teamsters, became a Trotskyist sympathizer. Patrick Corcoran, who led the local Teamsters Joint Council, became a critical ally of the Trotskyists in the campaign to unionize truckers throughout a six-state region of Minnesota, North and South Dakota, Iowa, Wisconsin and Upper Michigan. Corcoran’s about-face was obviously not appreciated in some circles. In 1937, gunmen murdered him late at night outside his house. The crime was never solved by the authorities.

What moved these officials was the role of the principled leadership of Trotskyism and a deep-going radicalization of the working class. Politically, on an international stage it was reflected in the development within many organizations of a left wing seeking a path to revolutionary socialism.

In 1936, the Trotskyist movement in the US entered the Socialist Party. When the conflict with the Socialist Party right wing reached its apogee in 1938, the Trotskyists emerged, having won over the left-wing elements, as the Socialist Workers Party (SWP). The same year saw the establishment of the Fourth International, to which the SWP was affiliated.