During World War One, 97 years ago, on December 24 and 25, 1914, along the western front, an unofficial ceasefire involving some 100,000 British and German troops took place. Just four months after the conflict started, the German and Allied armies had reached a stalemate bogged down in a vast network of flooded, freezing trenches undermining the pre-war patriotic fervour and claims it would all be over in a year.

The high commands soon set about stamping on this fraternisation between “enemy” lines with court martials, artillery barrages and orders to raid and harass enemy lines. The press eventually joined in, minimising the extent and content of the truces and decrying it as a treasonable offence. The following year, the number of ceasefires had reduced considerably, and by the third Christmas, they had become virtually non-existent.

Carol Ann Duffy’s latest book-length children’s poem reflects in sentimental tones the moments leading up to this extraordinary event. The opening verse sets the scene in Duffy’s clear, precise style:

Christmas Eve in the trenches of France

the guns were quiet.

The dead lay still in No Man’s land –

Freddie, Franz, Friedrich, Frank...

The moon, like a medal, hung in the clear, cold sky.

Duffy’s poetry penetrates the detail of life in the trenches in order to fuse the reader’s feelings with the intensity of the suspended moments of the truce. She describes the men huddling together, lighting their pipes or waiting for sleep. A young soldier stares at the same star that his mother may be gazing at simultaneously. The poem beautifully depicts a robin’s song:

In a copse of trees behind the lines,

a lone bird sang.

A soldier-poet noted it down – a robin

holding his winter ground –

And the very next line, the moment when

silence spread and touched each man, like a hand

The poem goes on to describe the horror of war through its evocative imagery of the damage it inflicted on the soldiers:

Men who would drown in mud, be gassed, or shot,

or vaporised

by falling shells, or live to tell,

Duffy’s trademark use of repetition is deployed concisely here and in service to, and acknowledgement of, the dual or international nature of the truces as the Germans began to sing and British troops

heard for the first time then –

Stille Nacht. Heilige Nacht. Alles schläft, einsam wacht . . .

The poem describes the singing as a “sudden bridge from man to man” that elicited cheering. The fraternisation from this point onwards gathers pace like a snowball with French, German and English songs being sung through the night, followed by gifts and exchanges of food, alcohol and cigarettes at daylight. There is more translation from Duffy as she charts the fast-growing warmth and communication between the soldiers:

I showed him a picture of my wife

iche zeigte ihm

ein Foto meiner frau.

Sie sei schon, sagte er.

He thought her beautiful, he said.

The soldiers also buried their dead in a part of the war-torn landscape described by

Richard Schirrmann (founder of the German Youth Hostel Association) as, “Strewn with shattered trees, the ground ploughed up by shellfire, a wilderness of earth, tree-roots and tattered uniforms.” This was the area known as “No Man’s Land” which became temporarily transformed by soldiers who allowed themselves to “Make of a battleground, a football pitch.”

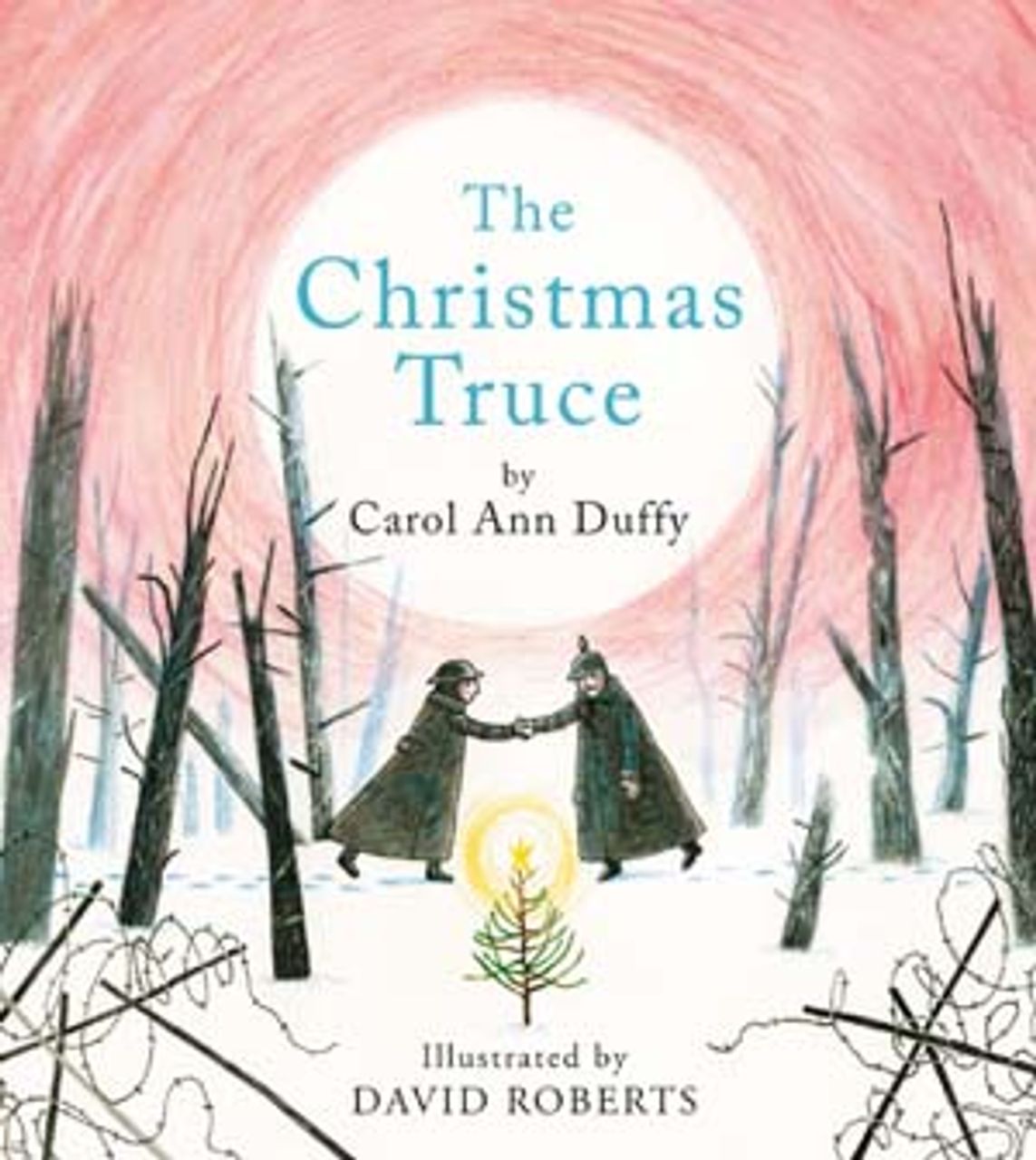

Duffy’s book is illustrated by David Roberts, and despite criticism regarding the type of helmets depicted in the drawings (they were not in use until 1916), the pictures serve to characterise the poignancy, dispossession and hardship of the trenches. The drawings are muted, frequently washed with shades of flint grey and smudged green. Much of the strong colouring is reserved for the soldiers’ cheeks, which are often flushed with the extreme emotions experienced in war—fear, paralysis, despair. The sole page that departs from the mute tones is the one containing the Christmas morning stanza; bathed in a gentle misted pink, with soldiers waving from the snow hills of barbed wire, it begins:

So Christmas dawned, wrapped in mist

to open itself

and offer the day like a gift

for Harry, Hugo, Hermann, Henry, Heinz . . .

with whistles, waves, cheers, shouts, laughs.

Duffy’s skilful use of alliteration and listing is shown to full effect in the poem, which powerfully conjures the moods of alienation or sudden interaction.

Press censorship and military oppression ensured that little information regarding the truces emerged, so that much of the information came directly from soldiers at the front or those wounded in hospitals. One of those who took part in the Christmas truce, Alfred Anderson, who died in 2005, recalled, “I remember the silence, the eerie sound of silence. Only the guards were on duty. We all went outside the farm buildings and just stood listening. And, of course, thinking of people back home. All I’d heard for two months in the trenches was the hissing, cracking and whining of bullets in flight, machinegun fire and distant German voices. But there was a dead silence that morning, right across the land as far as you could see. We shouted ‘Merry Christmas’, even though nobody felt merry.”

The Christmas Truce poem illuminates this silence but introduces into it:

Then flickering flames from the other side

danced in his eyes

as Christmas trees in their dozens shone,

candlelit on the parapets,

and they started to sing, all down the German lines.

Much has been written about World War One, and much of it by soldier poets—above all, the great Wilfred Owen. Carol Ann Duffy’s approach, in keeping with the Christmas theme, its appeal to children and her role as Poet Laureate, is fairly nostalgic, with an almost moonstruck aura, but very lyrical. Duffy has said of her own work, “I like to use simple words, but in a complicated way.” Owen, in contrast, who is not distanced by time or place, said of his own war poetry, “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.”

Duffy, born to a working class family in Glasgow, is the first-ever female Poet Laureate—a job traditionally appointed by the queen and which contains royal obligations. In 1999, she says she considered turning the role down, even if she had not lost out to the successful candidate Andrew Motion. Duffy, then in a relationship with fellow poet Jackie Kay, declared that “no self-respecting poet” should have to write verse about Prince Edward’s marriage, which took place that year.

However, in 2009, she justified her acceptance of the role on feminist grounds, telling listeners to BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour, “I think my decision was purely because there has not been a woman. I see this as recognition of the great women poets we now have...and I decided to accept it for that reason.”

In the same year, she commissioned a powerful new book, in which a variety of poets attempt to stamp their mark in their portrayals of the ongoing invasions and conflicts in the Middle East. Duffy’s own entry in this compilation, entitled “The Big Ask”, centres on a series of questions posed about Guantanamo Bay, the alleged weapons of mass destruction, Saddam Hussein and the roles of presidents Bush and Obama. Duffy creates penetrating images of a war crimes court with a tightly rhymed series of verses converging on the sound of “Barack”,

When did the President give you the date?

Nothing to do with Barack!

Were 1200 targets marked on a chart?

Nothing was circled in black.

On what was the prisoner stripped and stretched?

Nothing resembling a rack.

Guantanamo Bay - how many detained?

How many grains in a sack?

Extraordinary Rendition - give me some names.

How many cards in a pack?

Sexing the Dossier - name of the game?

Poker. Gin Rummy. Blackjack.

What’s your understanding of ‘shock’ and ‘awe’?

I didn’t plan the attack.

Once inside the Mosque, describe what you saw.

I couldn’t see through the smoke.

Your estimate of the cost of the War?

I had no brief to keep track.

Where was Saddam when they found him at last?

Maybe holed under a shack.

What happened to him once they’d kicked his ass?

Maybe he swung from the neck.

The WMD...you found the stash?

Well, maybe not in Iraq.

Duffy’s new poem The Christmas Truce continues in this anti-war vein, making sense of war and condemning its atrocities. Her attempts to bring the ceasefires and fraternisations to life for children are welcome.

The full poem can be found here http://www.my-best-books.co.uk/the-christmas-truce-2/