The United Auto Workers union lost another 76,000 members last year, bringing its total membership to 355,000. This is the lowest level since the late 1930s, just after the fledgling organization had won recognition at General Motors.

UAW membership fell by 18 percent in 2009, according to the union’s annual report filed Monday with the US Department of Labor. The losses were chiefly the result of the tens of thousands of job cuts the UAW accepted under the terms of the Obama administration’s forced bankruptcies of GM and Chrysler.

UAW membership fell by 18 percent in 2009, according to the union’s annual report filed Monday with the US Department of Labor. The losses were chiefly the result of the tens of thousands of job cuts the UAW accepted under the terms of the Obama administration’s forced bankruptcies of GM and Chrysler.

The UAW will lose another 4,600 members next week when the former GM-Toyota plant in Fremont, California, closes its doors, eliminating the last auto assembly factory on the US West Coast.

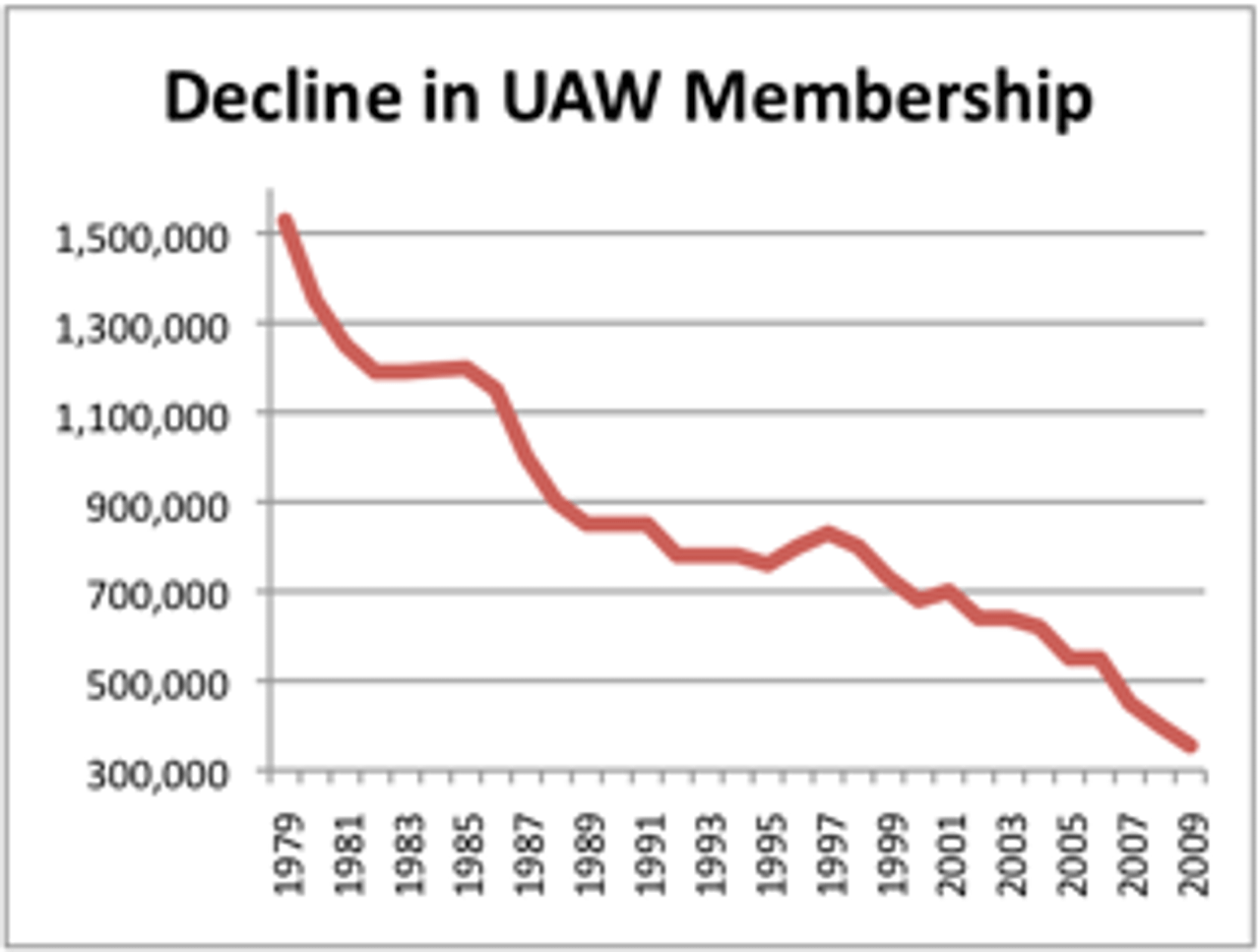

UAW membership has fallen by nearly half since 2001, when it had 701,818 members. Since reaching its peak of 1.53 million members in 1979, the union has lost 1.14 million members, or 77 percent of its membership.

The UAW largest local is no longer Local 600 at Ford’s River Rouge complex in Dearborn, Michigan, but a unit representing state public employees—which is also losing members due to state budget cuts.

According to the Detroit News, the UAW shut down 50 locals last year, reducing the total from 800 to 750, as plants closed and the organization’s Detroit headquarters consolidated locals to cut costs.

Michigan, long the center of the UAW, saw thousands of job losses in 2009 and continues to have the highest jobless rate in the nation. The restructuring of the auto industry—which has led to more than a 70 percent decline in Michigan’s auto-related employment since 1989—and the economic downturn over the last two years have led to sharp falloff in the membership of the UAW and other unions. The number of union members in Michigan fell by 60,000 last year.

Earlier in the year, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that the number of unionized hourly and salaried workers in the US declined by 771,000 to 15.3 million in 2009. Only 12.3 percent of all US workers were unionized—including just 7.2 percent in the private sector, compared to 35.7 percent of private sector workers in 1953 and 22 percent as late as 1979.

The disintegration of the UAW—a process that has been duplicated by trade unions throughout the US and in country after country—is the result of the reactionary policies and nationalist outlook that has long guided this organization.

The UAW emerged in the mass social upheavals of the 1930s, including the sit-down strikes in Flint and Detroit. By the 1940s, however, the socialist and other left-wing militants who pioneered the building of the UAW were purged from its leadership by the Reuther bureaucracy, which consolidated the UAW on the basis of an explicit defense of the capitalist system and an alliance with the Democratic Party.

Having tied the fate of the working class to what the UAW leadership perceived as the permanent dominance of American capitalism in the world economy, the UAW reacted to the rising challenge by Asian and European automakers in the 1980s and the globalization of auto production by abandoning any resistance to the attack on jobs and living standards and imposing the dictates of corporate management. In the name of increasing the “competitiveness” of the Detroit automakers the UAW suppressed every struggle against plant closings, mass layoffs and the unending demands for concessions.

The culmination of its corporatist program of “labor-management partnership” and “Buy American” nationalism was its collaboration with the Obama administration in the restructuring and drastic cost-cutting at GM and Chrysler. Over the past four years the UAW forced tens of thousands of older, higher-paid workers to leave the industry through so-called buyouts and agreed to contracts with GM, Chrysler and Ford that would put labor costs in line with Asian producers operating nonunion plants in the US South by reducing the wages of younger new hires by half. In addition, the UAW relieved the auto companies of billions in health care obligations owed to more than 1 million retirees and their dependents.

As the dues-based income of the UAW apparatus declined, it increasingly sought alternative means to secure the financial position and privileges of the army of union executives that run the organization. In exchange for its collaboration with the auto companies and the White House, the UAW was granted a substantial ownership stake of the US automakers, including 55 percent of Chrysler and 17.5 percent of GM, and essentially transformed itself into a business enterprise.

Despite the continuing hemorrhaging of its membership rolls last year, the UAW suffered only a small decline in net worth, the Labor Department reported. UAW assets were worth $1.13 billion in 2009, down slightly from $1.2 billion the year before.

On Tuesday, the UAW carried out a sale—conducted by Deutsche Bank Securities—of 362 million warrants in Ford Motor stock, representing an 11 percent ownership stake in the company. Ford issued the warrants—certificates entitling the bearer to buy securities at a given price—to the UAW in December, after the organization relieved Ford of $13.6 billion in medical cost obligations to 200,000 retirees and their spouses.

The sale was expected to raise $1.3 billion for the UAW-controlled retiree health care trust fund, known as the Voluntary Employees’ Beneficiary Association or VEBA. Commenting on the sale, the Financial Times of London wrote, “The union’s move to cash in the warrants comes after Ford’s share price has surged over the past year amid growing optimism about the company’s chances of emerging successfully from the crisis in its industry.”

The UAW has a direct financial stake in driving up the value of Ford shares through increasing the exploitation of auto workers and imposing further cost-cutting measures on its so-called members.

This only underscores the fact that auto workers can only defend themselves by breaking with this rotten organization and building a powerful political movement in opposition to the profit system and its defenders in the union apparatus.