Emily Carr: New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon, at the Art Gallery of Ontario (until 20 May 2007), the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (21 June-23 September 2007), the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta (25 October 2007-26 January 2008)

“More than most dead artists, Carr has acted as a mirror for the projection of others”—John O’Brian

The current touring exhibition of the work of Emily Carr (1871-1945) is the fourth retrospective since her death and offers the opportunity for a new generation to consider the work and legacy of an artist who has likely inspired more literature and scholarly attention than any other in this country.

Known for her paintings of British Columbia’s rainforest and its Indian villages, and in particular for her extraordinary images of totem poles, she later garnered acclaim for her autobiographical and fictional writing. According to one account, Carr “has been the subject of countless scholarly articles, several biographies, at least five art historical books, four documentary films, a handful of plays, a musical, a ballet, an opera, poetry, songs, and even a puppet show.”

In view of the particular place accorded Carr by Canadian cultural nationalists for their own narrow reasons, it is necessary to distinguish her objective historical role as an artist from her utility as a national emblem. The promotion of artists and their work to advance and define a ‘national’ culture has a long and tortured history. In the case of Carr it is particularly problematic and raises questions as to whose interests are being served by this effort. What use others have made of her—either as a symbol of national or some other identity—is a matter that should not be allowed to cloud an appreciation of her artistic contribution.

There is no doubt that Carr was an important figure, although it would be difficult to make the case that her style of painting was particularly innovative. She nevertheless represented something vital and inspired at an important historical moment.

And while it may be true that formally she broke little new ground, the combination of subject, time and place, as well as her extraordinary personality, makes her story and her work worthy of serious study.

In an age of pioneers

In 1863, having made a small fortune during the California gold rush, Richard Carr brought his wife, née Emily Saunders, and his family to follow the prospectors north and started a business as a provisioner in Victoria, British Columbia—what had been until then only a small British outpost. It was here, after decades of travel, that he settled and where young Emily was born in 1871, the second youngest of nine children.

Emily grew up as the family favorite and was especially close to her father—up to a certain age—when that changed dramatically. At some point during puberty—and few facts are clearly known—it seems there was an incident in which Emily was sexually traumatized by her father, an experience which deeply affected her and her relationships with men. At an early age she showed a rebellious spirit against her father’s autocratic ways, and an irreverence that often irritated her more conventional sisters. But in her early adult years she was subject to wide emotional swings that more than once saw her under medical care and in extended stays at a sanatorium.

Both of her parents died before she was seventeen and although business was not always good, Richard Carr was able to leave his children a sizable sum which sustained them, albeit modestly, for several decades until war and Depression took their toll.

At the age of 25, Emily undertook serious art study beginning at the California School of Design in San Francisco for three years, and another five years in England at the Westminster School of Art in London, among other institutions. In 1910 she concluded her European studies with a year at the Académie Colarossi in Paris, an experience that exposed her to the modern currents then shaking the art world and which had a lasting influence on her approach to painting.

In her training Carr was hampered by an apparent aversion to drawing from the nude, which she eventually overcame—but this too may have contributed to her preference for landscape painting over figurative work. And while she did paint some remarkable portraiture such as “The Women of Brittany” (1911), which also shows her strength as an impressionist, these were exceptions. Aside from her many paintings of Native village life, most of her figures were done as early caricatures in her amusingly illustrated travelogues.

In the early twentieth century, modernism was only beginning to have an impact in North America and it met with a less than warm reception in culturally conservative Victoria. Upon her return from Europe, enthused as she was by what she had learned from teachers like artist Harry Gibb in Paris, who had participated in exhibitions with Manet, Bonnard and Matisse, Carr continued to work in the style of bright colors and loose lines that she had embraced. Although disapproval was by no means universal, “violently modern” and “bizarre” were some of the terms Victoria’s critics used to discredit her work.

While she continued to gain public attention through the period of the First World War, it was not enough to sustain her either creatively or financially. Around that time she began to take in boarders to support herself and to produce Native-inspired crafts for tourists—some of which are included in this exhibition—and for the next decade or more, she did very little painting.

A late renewal

It wasn’t until 1927 that she gained any measure of real recognition and that was due to her fortuitous inclusion in an exhibition, which is partially restored in this show. Her works appeared beside those of some of her better known contemporaries such as Group of Seven luminary Lawren Harris, with whom she developed a close relationship.

Carr’s work is often associated with that of the Group of Seven, who were themselves claimed as a principal asset of “Canadian” heritage, and who painted similar natural themes on the other side of the continent. Although later works of this period are clearly inspired by Harris, his influence only accentuated an approach that was by now very much her own.

Relinquishing her earlier project of faithfully documenting the totems and villages of the West Coast Indians she had come to know and love, she began to grapple with what she conceived of as the more ‘spiritual forces of nature’ that Harris and others were promoting. He was influenced by Theosophy, the mystical current that promoted direct intuition, claiming to follow Hindu and Buddhist teachings, as a means of knowing divinity. But it was not an outlook she was ever entirely comfortable with and she eventually broke with Harris to return to a life of relative isolation.

Unlike some of the leading artists of her day such as Picasso or Braque, whose art was also influenced by non-European cultures—those of Oceania and Africa—and who were inspired to abstract the figure in ‘cubist’ forms, Carr’s exposure to Indian West Coast art was never really incorporated stylistically in her painting. For the most part, Native culture remained the subject rather than the object of her work, with the exception of some of her ceramic and rug-making craft, examples of which are included in this exhibition.

Yet her love for these people was clearly genuine and she developed important relationships within their communities, writing a great deal about her experiences among them in works such as the autobiographical “Klee Wyck,” written in 1941. The title derived from her Indian name, meaning ‘laughing one.’ The work drew enormous attention, and won her the Governor General’s Award, Canada’s highest literary honor, for nonfiction.

While much of her autobiographical writing was factually fairly unreliable, it was lively and showed a genuine kindness towards the Aboriginal peoples and a deep compassion for their plight.

Despite her literary inclinations, Carr was not theoretically inclined and did not much follow or take direct part in the philosophical debates that were stirring the art world in her day. She nevertheless at times displayed keen insight into some important questions. Upon her first exposure to figurative abstraction she questioned the artistic sincerity of some of the work she saw, saying, “distortion was often used for design or in an effort to shock rather than convince,” revealing a real concern for artistic truth. Reflecting on that critical juncture, she voiced her resistance to the influence of modernism: “I was not ready for abstraction. I clung to earth and her dear shapes, her density, her herbage, her juice. I wanted her volume, and I wanted to hear her throb.”

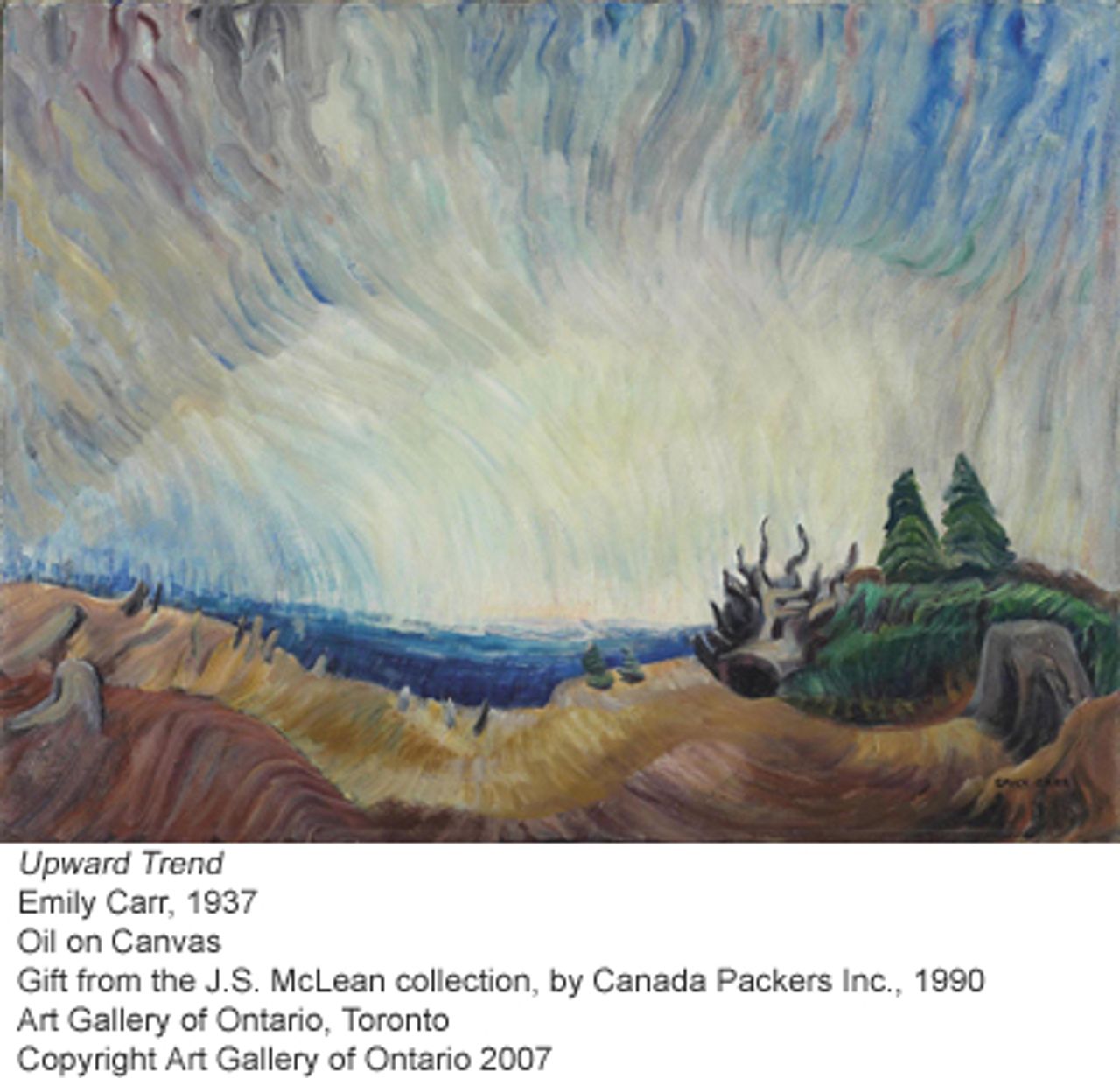

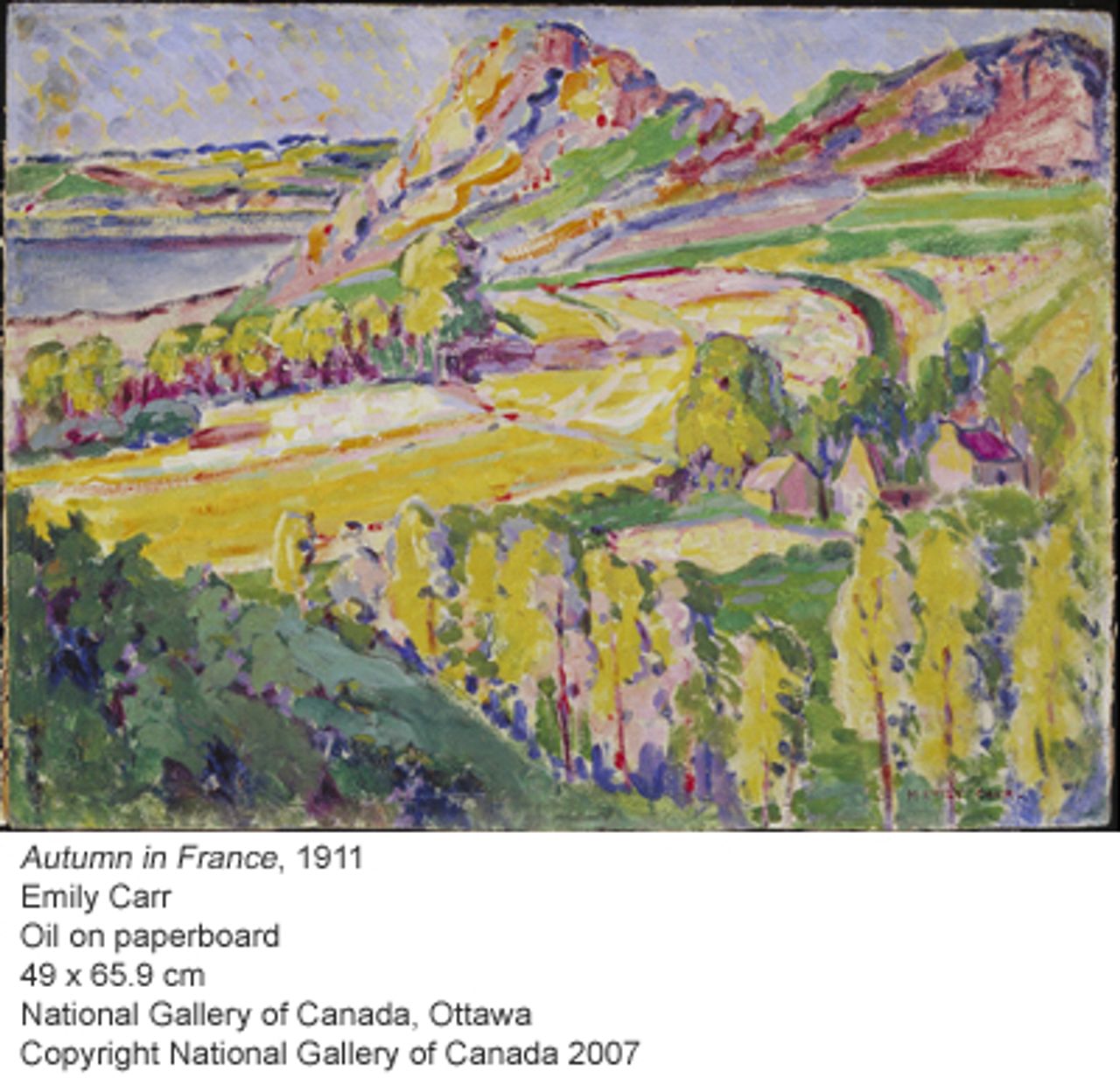

In her own terms, she painted in the “modern French style”—what we would call post-impressionism, although her work grew looser and more vibrant in later years. While it is unclear to what extent she was interested in contemporary currents, the explosion of modern art clearly had a profound impact on Carr’s painting, and in particular she was deeply influenced by both Fauvism and Cubism, leading movements of the time.

The Fauves (or “wild beasts”) was a loose grouping of painters early in the last century, including masters such as Matisse, who emphasized vivid, arbitrary color and simple form over the more representational schools of impressionism.

While paintings such as “Autumn in France” (1911) convey Carr’s embrace of the general approach of the impressionists, a piece such as “Trees in France,” done the same year, with its simpler shapes and brilliant yellows, shows the dramatic impact of Fauvism on her work.

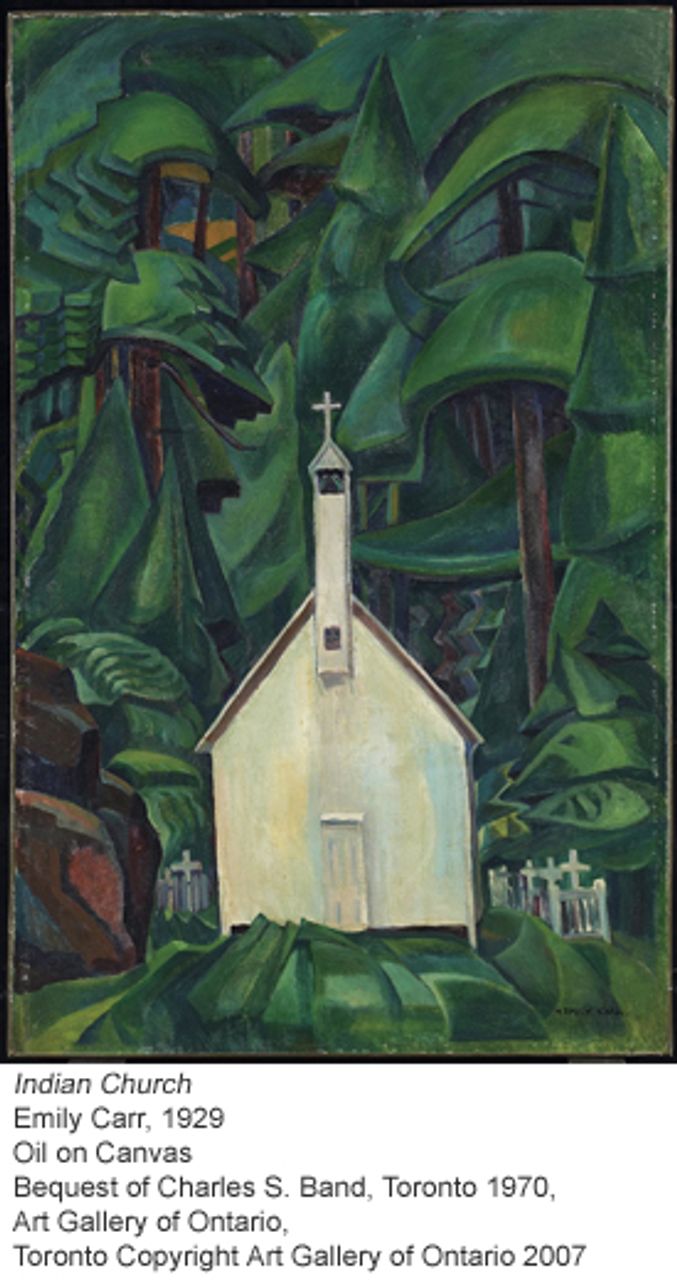

“Guyasdoms D’Sonoqua” is a painting that combines a kind of primitivism with a distinctly cubist simplification of form, as does the more well-known “Indian Church.” In the latter work, surrounded by ominous green shapes, a starkly pale Christian church is placed, more in two dimensions than three, as an intruder in a feral forest—emphasizing starkly the conflicting worlds brought together here. She was not fond of organized religion in general, while still being drawn to a personal faith, but this painting leaves her feelings about this juxtaposition open to interpretation.

Problems of identity

In considering the unique place that Carr has been given by the promoters of a Canadian art pantheon, some effort should be made to set the record straight. Carr herself was often angered by how she was largely ignored by the art establishment in her early years because she challenged both artistic tradition and the traditional role of women. In her day, however, Canadian national identity was not the political issue that it was to become.

The Canadian bourgeoisie was still consolidating itself and remained very much under the domination of the British Empire. Today this same ruling elite, beset by a series of increasingly acute global and national demands, along with the middle class layers that obey its dictates, places a different premium on national identity. Pursuing ambitions and policies that are increasingly at odds with popular opinion, the Canadian establishment has a keen interest in promoting or creating a common cultural heritage as a means of building a consensus for its “national interests.”

This helps explain why official Canada increasingly treats its leading cultural heroes with a measure of veneration that no mere mortals can merit. That unfortunately has been the case with Emily Carr.

As a pioneering ‘Canadian’ artist and a pioneering woman at that, she was all too well-positioned to meet the emerging need for a distinctly Canadian heritage. Moreover, the initial difficulties she had to surmount only added to her unprecedented stature. And while she may have even allowed herself to play the part of a living legend—how many artists would refuse such an opportunity?—what was in her time only a rather unseemly role has since been exaggerated in the intervening decades into something grotesque.

Canadian art historian John O’Brian comments in the exhibition’s catalogue: “The myth of Canadian identity for which her work was made to stand ... turned out to be problematic and far from innocent.” Like all legends, of course, it has come Carr’s turn to be “debunked.” O’Brian, for example, refers to claims in recent years that Carr has been overly praised, not made, as one might hope, by those opposing national parochialism, but by elements claiming to speak for Natives and for women artists.

According to O’Brian, some feminists have denounced the disproportionate promotion of Carr because it detracts from living female artists. And some First Nations leaders have attacked Carr for her appropriation of Aboriginal cultural forms in supposed colonialist fashion. Basing themselves on real historic injustices, these sorts of detractors speak only for a narrow layer and obscure her proper place in cultural history and the real problems of her legacy.

Carr readily acknowledged her debt to others in her success and particularly to Native influence: “Indian Art broadened my seeing, loosened the formal tightness I had learned in England’s schools. Its bigness and stark reality baffled my white man’s understanding.... I had been schooled to see outsides only, not struggle to pierce.”

Deeply distressed by the destruction of both Native culture and the old growth forests, much of her work can be seen as a protest to the plundering of both. Throughout her life, Carr displayed a greater comfort with the company of animals than people, often keeping dozens of pets, from goats to monkeys, in her care. By all accounts she was a difficult person, insecure and subject to bouts of deep depression and loneliness. But she found companionship in remarkable places, as with the sometime prostitute Sophie Frank, an Indian and one of her most enduring friends.

By the end of her life, Carr was suffering from numerous ailments and died ultimately of a blood clot in her heart. Whatever her personal shortcomings, she maintained an insatiable curiosity and a dedication to her work that drove her to paint through her declining years, even while fighting confining illness.

Mythology aside, learning about what this woman did and when she did it is itself ample cause for admiration. To see the Pacific Coast of Canada and its awesome beauty, and then to travel back to the time when Carr painted these scenes, knowing that no one had done this before, is to understand the deep feelings and impulses that must have driven her. The difficult terrain, the hostile cultural environment that she battled to do her painting, the fact that she was a woman starting out in the Victorian age (in Victoria no less!) and handicapped by all that meant; considering all these obstacles, one begins to get the measure of her strength and commitment.

Her own words remain as antidotes to the corruption of her legacy, and her art, taken on its own, will continue to project an extraordinary time and place.