Today marks the thirty-fifth anniversary of the assassination of Tom Henehan, a member of the Political Committee of the Workers League—the predecessor of the Socialist Equality Party in the US.

Tom was born on March 16, 1951 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He joined the Workers League in March 1973, dedicating his life to the political education and liberation of the working class.

During his four years in the party, Tom played a central role in the development of the youth movement in the US and internationally and was particularly active in expanding the Workers League’s influence among coal miners in West Virginia and Kentucky. He left an immense and unforgettable impression on all those whom he knew and with whom he worked.

We republish below an article written by Patrick Martin in 2007, on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of Tom’s assassination. Published separately is a tribute delivered in 1997 by David North, national chairman of the SEP, “Tom Henehan: A Revolutionary Life.”

***

Tom Henehan leading the Gary Tyler march through Harlem, December 1976

Tom Henehan leading the Gary Tyler march through Harlem, December 1976The political campaign to bring Tom Henehan’s killers to justice

By Patrick Martin

On the evening of October 15 1977, Tom Henehan, a member of the political committee of the Workers League, the forerunner of the Socialist Equality Party, was supervising an activity sponsored by the Young Socialists, the party’s youth movement, held at the Ponce Social Club in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn, New York.

Toward 1 a.m., two men, later identified as Edwin Sequinot and Angel Rodriguez, started a disturbance near the entrance to the hall by attacking another Workers League member, Jacques Vielot. As Tom rushed to Vielot’s aid, he was shot five times by a third assailant lying in wait, a professional gunman named Angelo Torres.

When Vielot sought to help Tom, Torres turned to him, put the pistol to his head, and pulled the trigger. When the gun did not go off, he slugged Vielot with the gun butt. Sequinot also pulled out a gun and shot Vielot, severely wounding him.

The injured Vielot rushed Tom to Wyckoff Heights Hospital. Although he was bleeding profusely, Tom was still conscious. However, he was left in the emergency room and no attempt was made to operate to stop his internal bleeding, though this is standard medical practice. Tom went into shock and died at 2:45 a.m. on October 16, approximately 90 minutes after arriving at the hospital. He was 26 years old.

Tom Henehan was the victim of a political murder—an attack aimed at eliminating a young cadre of the Trotskyist movement and intimidating the party’s struggle for socialism in the American and international working class.

The New York City Police Department (NYPD) made it clear they had no interest in seriously investigating the crime or arresting those responsible. Asked what was being done to arrest the killers, who had been identified at the scene, homicide detective John Mohl told Workers League National Secretary David North, “Henehan was just a commie and his death would be of interest only to other commies.”

The New York City police carried out no investigation of the killing and refused to arrest either Torres or Sequinot, who were quickly identified by eyewitnesses. Despite the evidence, the police claimed that Henehan was the victim of a “senseless killing” by a lone assailant, Torres.

Soon after Tom’s death, the Workers League and the Young Socialists launched a campaign to demand the arrest and conviction of his killers. For nearly three years, every issue of the Workers League’s newspaper, the Bulletin, carried a front-page appeal to demand the arrest and prosecution the two gunmen, Torres and Sequinot, and a full investigation into all the circumstances surrounding Tom’s death.

At factory gates, at coal mines, at shopping centers and college campuses, members of the Workers League and Young Socialists explained that the murder of Tom Henehan was a political attack at the entire working class. It was aimed at intimidating the Workers League and blocking its efforts to build a socialist leadership in the American working class. Tom’s death came at a point when the party was gaining significant influence among city workers in New York, coal miners in West Virginia and Kentucky and other sections of militant workers.

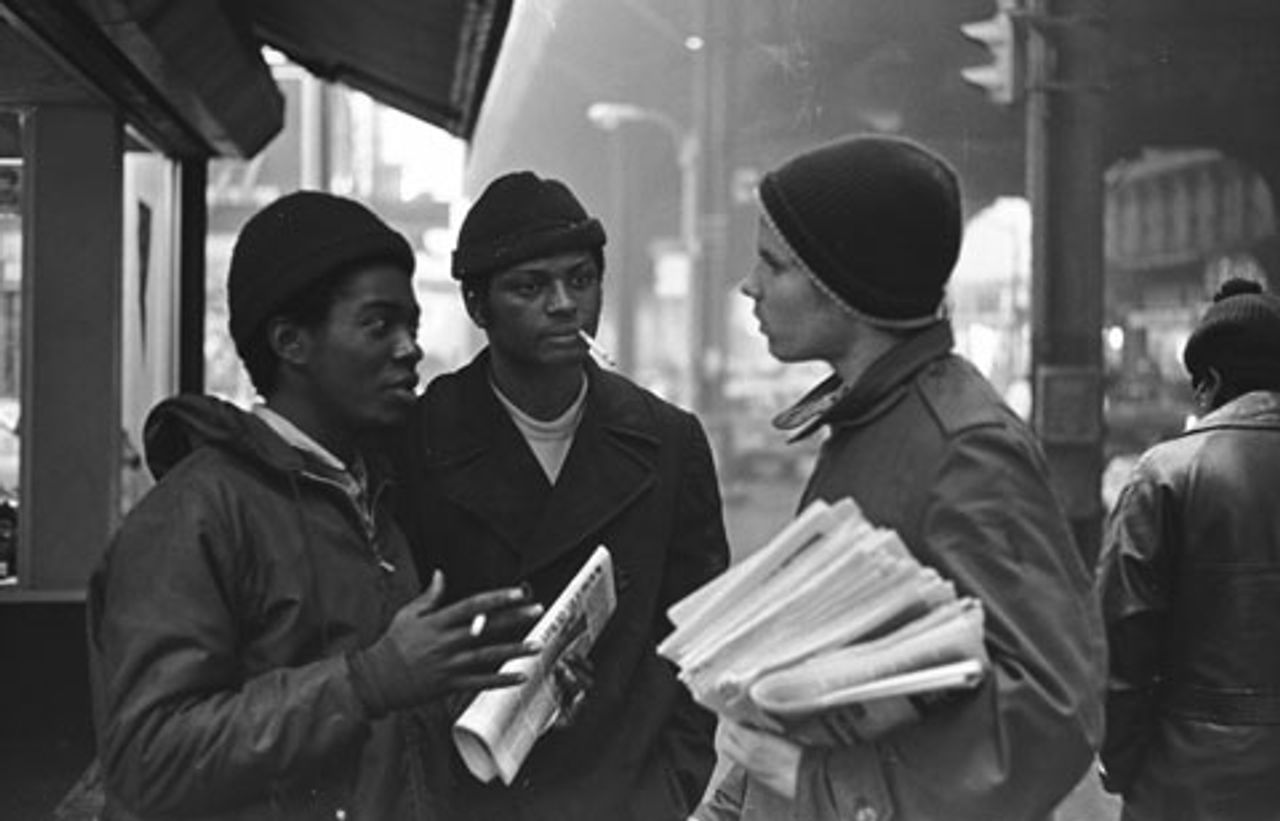

Tom Henehan campaigning among youth in Brooklyn, January 1975

Tom Henehan campaigning among youth in Brooklyn, January 1975On May 11, 1978, the Workers League sent a letter to the Brooklyn District Attorney, pointing out that the police, by ruling out a political motivation for the killing, were demonstrating that they had no intention of either bringing the murderers to justice or determining who had organized the crime. We wrote:

“It is strange, to say the least, that the police would so quickly rule out politics as a motive for the shooting of a well-known political leader in the workers’ movement. Had the victim been a prominent leader of either the Democratic or Republican parties, the first assumption that would have been made is that the crime had a political motive.”

The letter pointed out that the police had supplied false information to the press in order to bolster their claim that the murder of Tom Henehan was a “senseless killing” by a single enraged gunman. This was directly connected to their refusal to arrest Sequinot, whose address in Brooklyn was well known to them. Why were the police protecting Sequinot, the letter asked.

The letter also pointed out that the bullet extracted from Jacques Vielot’s thigh was of a different caliber that those taken from Tom Henehan’s body, further undermining the “one-gunman” theory advanced by the police.

The campaign for an investigation into the death of Tom Henehan won widespread support from workers and youth throughout the country, including tens of thousands who signed petitions to the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office. Officials from unions representing three million workers in the US also endorsed the campaign, including top officials of the unions representing machinists, meatcutters, auto workers, actors, baseball players, hospital workers, teachers and steelworkers.

The campaign unfolded and gathered strength under conditions of major struggles by coal miners, auto workers, firefighters, public service workers, airline workers and hundreds of thousands of others, including a strike by New York City transit workers in which Ed Winn, later the presidential candidate of the Workers League, played a prominent role.

This support was won in the working class in the face of a cover-up by the corporate-controlled media, including both the New York Times and New York’s two tabloid dailies, which abandoned their usual sensationalism about violent crime and maintained complete silence on the brutal gunning down of a socialist political activist in Brooklyn.

Equally important, and even more reprehensible, was the silence from the Stalinists of the Communist Party, from the Socialist Workers Party, and from other political tendencies of the left.

Under growing pressure from the Workers League’s campaign, the police finally arrested Angelo Torres on a bus in Brooklyn on October 15, 1980, almost three years to the day after Tom’s murder.

It soon emerged that Torres had been living in his apartment all along and had made no attempt to hide. Nor did he attempt to flee the city to escape arrest and prosecution. On the contrary, police records showed that he had been arrested in New York City for minor charges in June 1979 and released, although a fingerprint check would have shown an outstanding arrest warrant for murder.

Several months later, in December 1980, after long denying that a second gunman was involved, the police arrested Edwin Sequinot. Both Torres and Sequinot were indicted for murder and attempted murder. The two men were convicted by a Brooklyn Supreme Court jury in July 1981 and sentenced to long prison terms for acting in concert in the murder of Tom Henehan and the wounding of Jacques Vielot.

Torres was found guilty of second degree murder, attempted second degree murder and a weapons possession charge. He was sentenced to consecutive terms of 25 to life and 12.5 to 25 years. Sequinot was convicted of first degree manslaughter and attempted second degree murder, and sentenced to two consecutive terms of 12.5 to 25 years in prison.

The jailing of the killers, however, left many unanswered questions about the case.

Neither gunman had met Tom Henehan before the night when they teamed up to kill him. Torres, who fired the fatal shots, was a reputed contract killer. Rodriguez, who lived in an apartment above the Ponce Social Club, was undoubtedly aware of the political nature of the Young Socialists activity taking place there, which had been widely publicized in the neighborhood.

All three attackers had unexplained and highly suspicious relations with the police.

Sequinot was on prison work-release and under police supervision at the time of the murder. He was called in for questioning, identified by eyewitnesses, and then released. Three months later, despite being named as a murder suspect, he was paroled by New York state. For the next three years, despite being identified by eyewitnesses as participating in a murder and attempted murder, Sequinot lived undisturbed in Brooklyn, not so much as changing his address.

Torres was arrested by the NYPD in June 1979 and then released. At the trial, Judge Sybil Kooper ruled that the prosecution could not charge that Torres had attempted to flee as an argument that he was conscious of his guilt. There was no evidence of flight, she said, acknowledging that there had been no attempt to arrest him.

Rodriguez was never charged in the case or even called as a witness, despite being in prison on other charges at the time of Torres’s arrest. Rodriguez was not indicted for his role in the crime, although his full participation was spelled out throughout the trial of Torres and Sequinot, beginning with the opening statement by Assistant District Attorney Barbara Newman.

Trial testimony confirmed that Rodriguez had joined in the assault on Vielot, using a pool cue while Torres attacked with his fists, before drawing his gun. Rodriguez fled the scene as part of a trio. Under the legal principle explained to the jury by Judge Kooper, in which those acting “in concert” in the assault were individually guilty of all the acts committed, Rodriguez was guilty of murder and attempted murder.

The details of his long criminal record suggest that he may have been a police informant. He was arrested ten times in the eight years preceding the trial of Torres and Sequinot, and was released on parole on December 9, 1980, less than two months after the arrest of Torres. Rodriguez testified to the grand jury that indicted Sequinot. Yet he did not appear at the trial, either as a witness or defendant.

Police handling of the physical evidence of the case suggests criminal negligence or outright cover-up. The bullet removed by surgeons from Jacques Vielot’s thigh on October 16, 1977 was not picked up by police until November 1980, after the arrest of Torres. A police witness at the trial testified that there was a fourth bullet that was never recovered because it was behind a wall—an obstacle apparently too great for what the police claimed was an “extensive” investigation.

The weight of evidence demonstrates that Tom Henehan was the victim of a politically motivated killing which was then covered up by the New York City authorities. Torres, Sequinot and Rodriguez were only the instruments. The identity of those who commissioned this killing still remains to be determined.