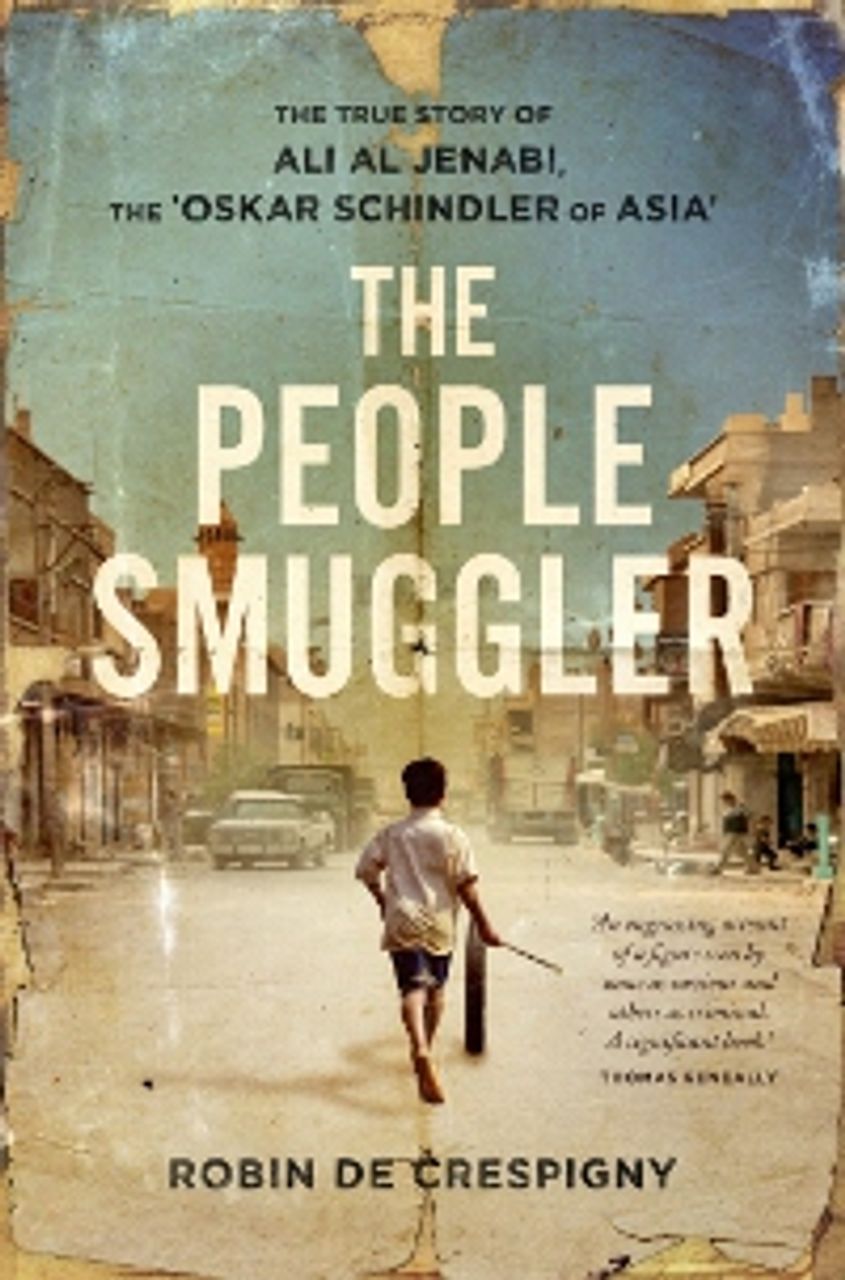

Book review: The People Smuggler by Robin de Crespigny, Penguin 2012.

“People smuggler” is a term concocted by Australian governments over the past two decades to demonise all those who assist refugees, fleeing persecution and oppression in their homelands, to get on boats to seek asylum in Australia.

The current Labor government of Prime Minister Julia Gillard has vowed to “smash the people smugglers’ business model,” and thus stop the arrival of refugee boats, by deporting asylum seekers to Malaysia or Nauru.

The current Labor government of Prime Minister Julia Gillard has vowed to “smash the people smugglers’ business model,” and thus stop the arrival of refugee boats, by deporting asylum seekers to Malaysia or Nauru.

Gillard and her ministers depict those who organise refugee boats as ruthless profiteers making fortunes out of human misery. According to Gillard, they are “evil” individuals who “prey on the desperation of people.”

By recounting the life of Ali Al Jenabi, one of the first men to be tried in Australia for so-called people smuggling offences, Robin de Crespigny’s The People Smuggler puts a human face on those involved in the boat voyages. What emerges is a harrowing picture of a man whose only “crime” was to escape severe repression in Iraq, and seek safety for his mother and six younger brothers and sisters.

Along the way, the book exposes many of the anti-refugee myths peddled by Australian governments. It also points to the complicity of successive governments, and the police and intelligence agencies, in organising key anti-refugee operations, notably the voyage of the SIEV X, the vessel that sank in October 2001 at the cost of 353 lives.

Derived from three years of interviews with Al Jenabi, the book is written as his first-person account, starting with his childhood in the southern Iraqi city of Diwaniyah during the 1970s. It reads as a frank story, of an ordinary and sometimes troubled man, confronted by terrible events.

One of nine children in a Shiite family, he was forced to take responsibility for his younger siblings after his outspoken father had been detained by Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime, tortured and finally released a broken and mentally-ill man.

Following the first US-led invasion of Iraq in 1990-91, and Saddam’s repression of the subsequent Shiite uprising, Al Jenabi and the family fled Diwaniyah, together with most of its residents. The American government had offered the Shiites support if they rose up against Saddam. “But as soon as the uprising started, the US left us to our fate, and the full weight of Saddam’s army was turned on us,” he recalls. “They moved swiftly through the mostly Shiite southern cities, imprisoning, torturing and killing all the young men and anyone suspicious.”

Eventually forced by hunger, rain and cold to return home, Al Jenabi was picked up by the secret police and sent to Baghdad’s notorious Abu Ghraib prison, where he, his father and his younger brother Ahmad were cruelly tortured. Ahmad died as a result.

After his release, Al Jenabi escaped to Iraqi Kurdistan to join groups seeking to overthrow the regime, but became disillusioned by the infighting between the various factions, bankrolled by American, British, Iranian or Syrian intelligence agencies.

He returned to his family, only to be detained and conscripted. After deserting the army, and threatened with execution if he were caught, he fled to Iran with his mother, brothers and sisters. From there, they made a desperate bid to reach Europe overland via Turkey, but were rounded up in Istanbul and removed back to Iraq.

Another escape to Iran led to a formal application for refugee status, via the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Pakistan. After a difficult seven-month wait, the application was rejected. “The UN deems our plight is not sufficiently serious for us to qualify as refugees, and refuses the whole family. By their criteria we have not suffered enough.”

As a last resort, urged on by his mother, Al Jenabi paid for a false passport and flights to Indonesia, and the chance of finding a boat to take him to Australia.

In Indonesia, Al Jenabi struck a deal to work for a boat organiser in return for members of his family being placed on boats for free. After various bitter experiences, he decided to organise boats himself, to earn the money needed for their flights.

“There is no law in Indonesia against people smuggling. It is just another business, one which provides a path to asylum for refugees who have no other options. So I will do it myself the way it should be done. I will not only save my family. I will save other Iraqis, and everyone I help escape will feel like a personal victory over Saddam.”

Before long, Al Jenabi was besieged by refugees, determined to make the voyage to Australia, knowing that less than 2 percent of the thousands of asylum seekers waiting in Indonesia ever get resettled by the UNHCR. By 2001, he had successfully organised seven boats, whose passengers, including his loved ones, arrived safely in Australia, where they were all eventually granted refugee visas—after months of detention.

Al Jenabi’s enterprise bore no resemblance to the supposed “people smugglers’ business model.” His fares were as low as $700. Children travelled free or for half price. There were reduced rates for passengers who could not afford to share the full costs of buying the boats, hiring the crews, arranging accommodation and paying the necessary bribes to Indonesian officials.

The desperation of refugees to get on boats intensified after the Australian government, in late August 2001, refused entry to the 433 asylum seekers rescued by the Tampa, a Norwegian container ship, and then exploited the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the US to associate refugees with terrorists. Anxious to sail before the Australian door was closed completely, 353 people joined a hopelessly overloaded boat, later dubbed SIEV X, organised by one Abu Quassey.

The Australian government of Prime Minister John Howard seized upon the sinking of the SIEV X to pursue its political agenda of stopping refugees from seeking asylum in Australia. Immigration Minister Philip Ruddock said the disaster “may have an upside, in the sense that some people may see the dangers inherent in it [seeking to sail to Australia].”

Later, Al Jenabi discovered that among those working with Abu Quassey on the SIEV X operation was a man who had been providing information on refugee boats to the Australian embassy in Jakarta since August 2000. Identified only as “Weasel,” this agent had been paid up to $US300 a week for his information. “Weasel” was subsequently flown to Australia as a guest of the AFP to testify against Al Jenabi.

This informer’s role raises new questions about the Howard government’s involvement in the SIEV X tragedy, into which no inquiry has been conducted, and for which no one has been held politically responsible to this day (see: “Did the Australian government deliberately allow 353 refugees to drown?”).

In late 1999, another AFP agent tricked Al Jenabi—who had decided to quit the refugee trade—into flying to Bangkok, ostensibly to join a restaurant business. On his arrival, he was detained and extradited to Australia to become the subject of a highly-publicised “people smuggler” trial.

As evidence emerged of Al Jenabi’s true motives, the show trial started to backfire. After 37 days, Al Jenabi’s lawyers struck a bargain with the prosecutors. He pled guilty to reduced charges relating to two boats and was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment, with parole available in two years. The judge conceded that he was largely motivated by the need to get his family to Australia, and that his passengers arrived safely.

Bitterly, Al Jenabi compared his fate to that of “Weasel,” a “confessed people smuggler himself,” who “received $250,000, Australian citizenship, and indemnity from prosecution, as a reward for informing to the AFP.”

Al Jenabi’s imprisonment was followed by almost another two years in Sydney’s Villawood immigration detention centre, because the government secretly blocked his refugee application. Al Jenabi was then fed false hopes by lawyers and refugee rights activists that the Labor government, which took office in 2007, would grant his visa.

Exactly the opposite has occurred. Al Jenabi was granted only a Removal Pending Bridging Visa, leaving him vulnerable to being sent back to Iraq, and making it impossible for him to be joined by his fiancé in Iraq or his young daughter in Indonesia, or to visit his dying father.

Immigration Minister Chris Evans was intent on enforcing Labor’s “border protection” policy. Confronted by Al Jenabi at a public event, Evans told him: “Smuggling is a serious crime and the Australian people won’t forget it.” Evans’s ministerial successor, Chris Bowen has maintained that stance, rejecting a May 2011 Human Rights Commission recommendation that Al Jenabi receive compensation and an apology.

De Crespigny, however, draws no political conclusions in the book. In a question and answer page on Penguin’s promotional web site, the film maker and first-time author expresses the hope that the book will “change the direction of the debate about refugees by touching people who had previously never asked themselves what they would do if they were in the same situation.”

Undoubtedly, these sentiments reflect a growing revulsion felt by wide layers of people about the treatment of asylum seekers. Yet, her approach tends to blame ordinary people, not the governments that have fomented anti-refugee prejudice. For the current Labor government, like its predecessors, the arrival of refugee boats is a convenient means of distracting attention from its responsibility for the deepening assault on jobs and social conditions.

Despite its political limitations, De Crespigny’s book makes a valuable contribution in dealing insightfully and humanely with the terrible ordeals of people whose only “crime” is to seek refuge and a better life for themselves and their families.