London’s Tate Modern art gallery is hosting a temporary exhibition of John Heartfield’s political photomontages from the 1930s, drawn mainly from the collection of British photojournalist David King. (See “Uncovering the truth about Trotsky and the Russian Revolution ‘continues to run my life’”) They cover the period from 1930 to 1938 when the artist contributed 237 photomontages to the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) magazine, Volks Illustrierte (People’s Illustrated).

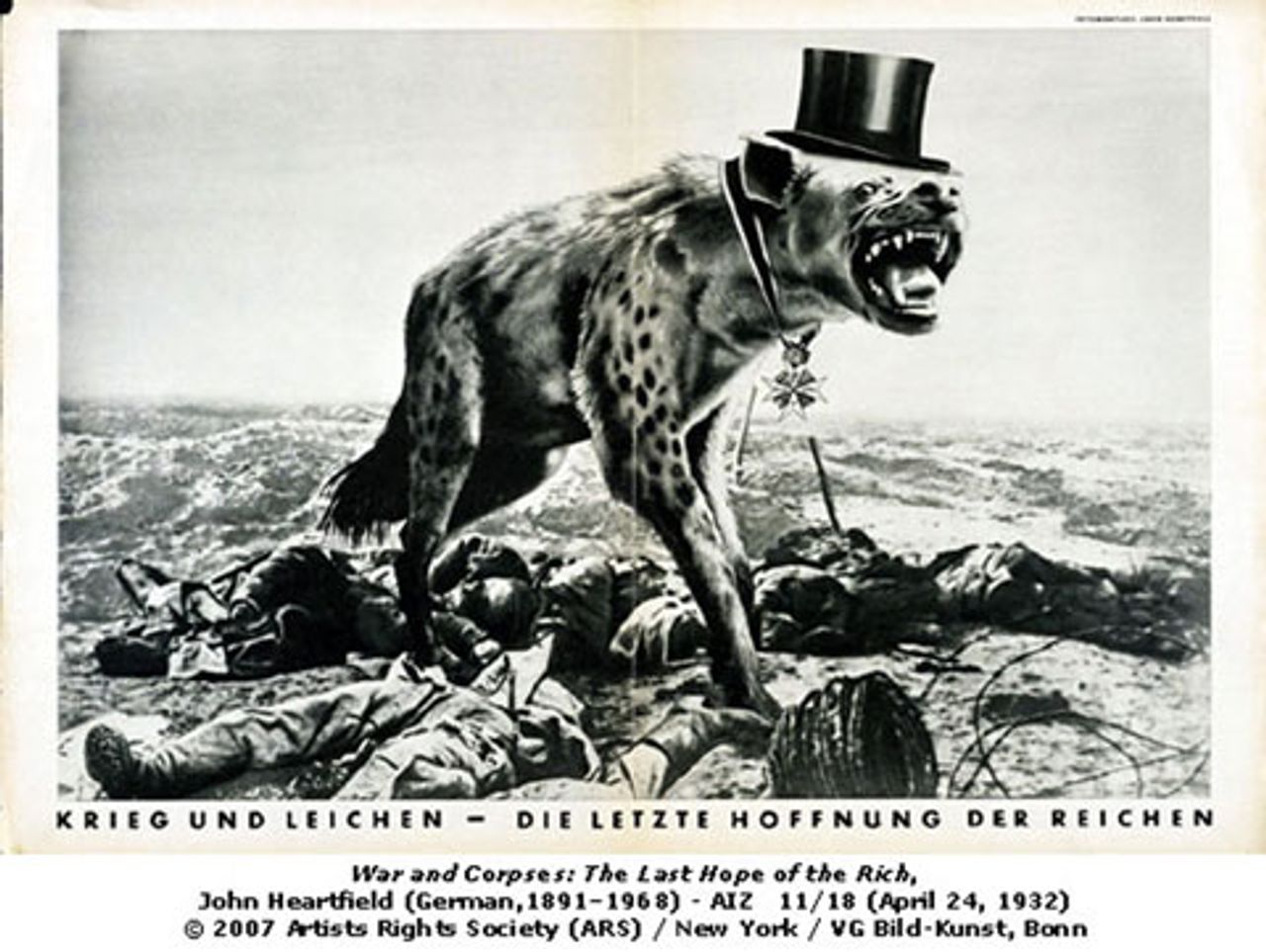

“War and Corpses: The Last Hope of the Rich” (1932)

“War and Corpses: The Last Hope of the Rich” (1932)The show provides a welcome opportunity to see Heartfield’s political montages. At their finest the works burn with a revolutionary hatred for bankrupt and barbarous capitalism. They also offer the opportunity to reflect on the political confusion created by the betrayal of the German working class by the Stalinist KPD, which paved the way for Hitler and the Nazis to gain power.

Heartfield’s work can only be understood in the context of the political developments of his age. It was a direct response to the situation around him.

He was born Helmut Herzfeld in 1891, and his brother Wieland five years later. Their parents were both political. Their mother Alice was a textile worker and their father Franz (who wrote under the name Franz Held) was an early Expressionist writer. Held’s work championed international unity and met with hostility from the establishment. Found guilty of blasphemy, he was forced to flee the country. Both parents left the boys and their sisters in 1899.

The four children were dispersed to various guardians. In 1908 Helmut studied at the Royal Bavarian Arts and Crafts School in Munich, where he was influenced by commercial designers Albert Weisgerber and Ludwig Hohlwein.

By 1912 he was employed designing book jackets. Several from the 1930s are included in the Tate room. He moved to Berlin in 1913 to study under Ernst Neumann at the Kunst und Handwerkerschule, on the eve of the First World War.

Heartfield’s artistic development was shaped by the escalating militarism that saw the collapse of the Second International in 1914 due to the growth of social chauvinism. With the outbreak of war most of the social democratic parties moved to support the war aims of the ruling class in their own countries. The largest and most influential, the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD), led the way in this betrayal.

Helmut was drafted into a regiment in Berlin. Wieland was sent as a medical orderly to the Belgian front, but was later removed from his post for insubordination. Helmut, threatened with a transfer to the front, faked a nervous breakdown and was discharged.

Back together in Berlin the brothers began collaborating artistically. Their actions were a calculated rejection of German imperialism. In 1916, sickened by the nationalistic slogan “Gott strafe England” (May god punish England), Helmut changed his name to the anglicised name John Heartfield. The brothers’ mutual friend, the artist George Groß, also changed his surname to Grosz. Such reactions point to the artistic climate of revolt that would find expression in Dada.

Although Heartfield had some official work during the war (working in the Military Educational Film Service), he was moving toward an explicit rupture with the existing order. In the period following the 1917 Russian Revolution, he joined both the newly formed KPD and the Berlin Club Dada.

In 1919 Heartfield was dismissed from the Film Service for calling for strike action in response to the murders of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. In the wake of the suppressed German revolution of 1918-19, the revolutionary leaders were murdered by gangs under the social democratic minister Gustav Noske. The SPD lined up with the high command of the army to crush the revolution.

Berlin Dada was more explicitly political than other Dadaist groups. The work of Heartfield, his brother, Grosz, Hannah Höch, and Raoul Haussman was marked by an interest in mass media forms and direct political comment. Heartfield was one of the organisers of their 1920 First International Dada Fair, the only such international exhibition during the movement’s lifetime. Its centrepiece was a dummy with a pig’s head, dressed as a German officer, hanging from the ceiling.

Heartfield resisted the label “artist”, referring to himself as an engineer. He continued to pursue satirical and political work, editing satirical magazines, as well as working for KPD periodicals like Die Rote Fahne. He was an integral part of Berlin’s wider artistic and political scene, working closely with the playwrights and directors Bertolt Brecht and Edwin Piscator.

In 1924, on the tenth anniversary of the beginning of the war, Heartfield showed his first photomontage, “After Ten Years: Fathers and Sons”—in which skeletons parade behind an imperial general. The montage technique became a central part of his work, enabling him to address the issues of the day. Some, like his electoral campaign posters, were straightforward propaganda. Other pieces combined his satirical vision with political comment. In 1929 he produced a montage of himself slicing the head off Zörgiebel, Berlin’s SPD police chief, under the caption, “Use photography as a weapon”.

“Forced Supplier of Human Material, Take Courage!” (1930), shows a dazed-looking pregnant woman sitting before a background of corpses. It is stark and moving. Heartfield’s generation knew the carnage of imperialist war, and the implications of another one.

“Twenty Years Later!” (1934) features children training as soldiers.

In “War and Corpses: The Last Hope of the Rich” (1932), a hyena in a top hat stands snarling on top of a pile of corpses. The hyena wears a medal, its motto changed from “For merit” to “For profit”.

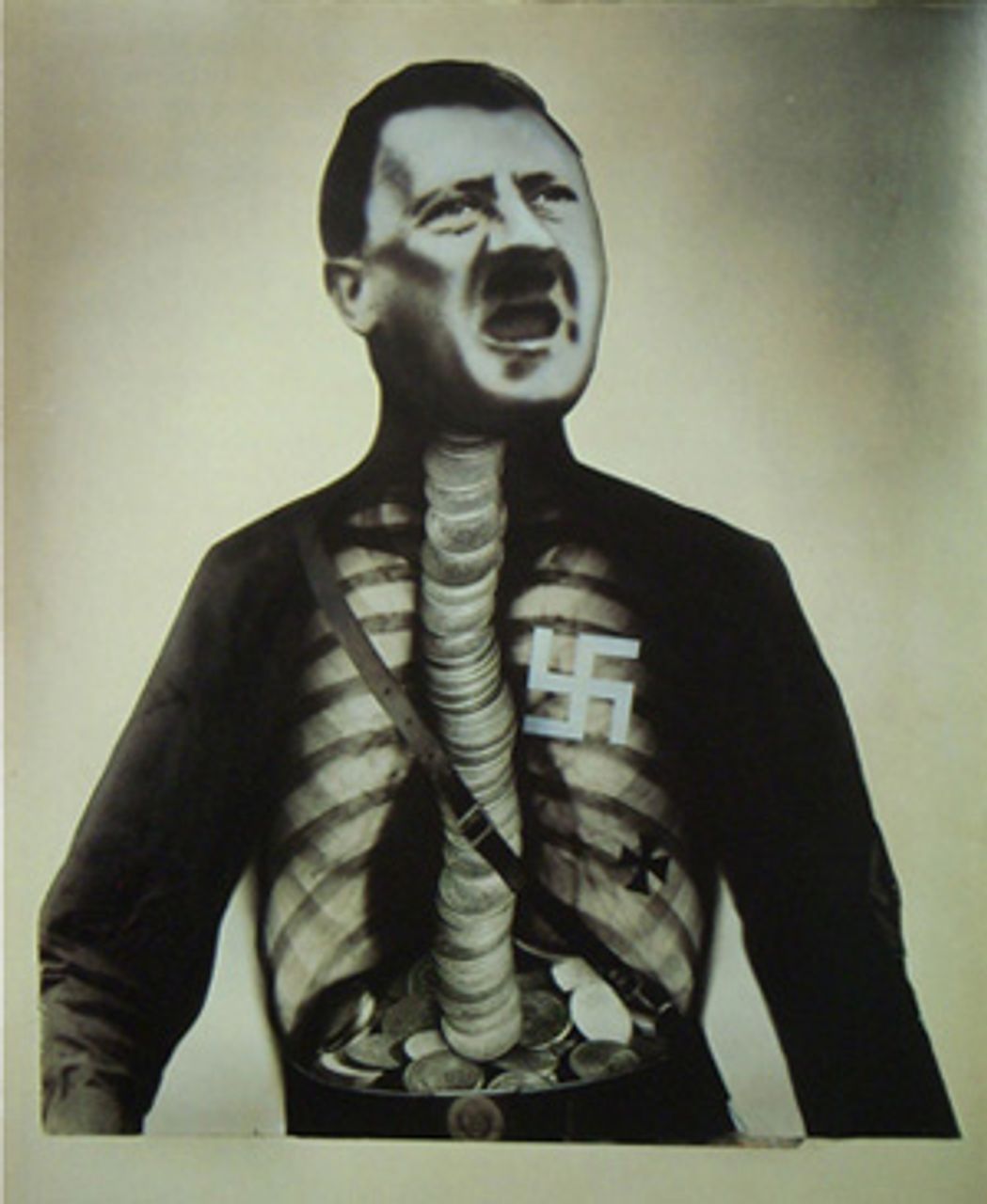

“Adolf, the Superman: Swallows Gold and

“Adolf, the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Rubbish” (1932)

Heartfield is particularly sharp on the interests being defended by the developing fascist movement. Hitler is represented as the last line of defence for finance capital.

In “Adolf, the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Rubbish” (1932), an x-ray reveals that Hitler’s spine is made of coins. In the famous “The Meaning of the Hitler Salute: Little Man Asks for Big Gifts. Motto: Millions Stand Behind Me!” (1932), the diminutive Hitler receives money in his upraised palm from the enormous banker behind him.

Other images are less familiar, but equally powerful. “The Röchling Calculation” (1934) shows the industrialist Hermann Röchling calculating the benefits of fascism in the formula “Hitler = enslavement of the people. Enslavement of the people = increased profit. Increased profit = my ideal. Therefore: Hitler = my ideal!”

“The Thousand Year Reich” (1934) shows a tottering house of cards, with the German industrialist Thyssen at the top supported by Goering and Hitler at the bottom.

Heartfield’s savage images are a blunt warning of the brutality of fascism. He stresses connections with earlier forms of repression. “The Old Motto of the ‘New’ Reich: Blood and Iron” (1934) echoes Bismarck’s 19th century slogan in an image of bloody axes lashed together in a swastika. “As in the Middle Ages … So in the Third Reich” (1934) compares a medieval martyr broken on a wheel with a figure broken across the arms of the swastika.

These are remarkable and stunning images, but there is a tragic element to them. Heartfield’s savage and accurate assessment of the character of fascism went hand in hand with his espousal of the political line of the KPD, which served to disarm the German working class against the rise of Hitler. At a time when millions of workers still supported the SPD, the Stalinists characterised the social democrats as “social fascists”, thereby preventing any unity between those socialist workers and the communist movement and their being won to a revolutionary perspective.

“The Old Motto of the ‘New’ Reich: Blood

“The Old Motto of the ‘New’ Reich: Blood and Iron” (1934)

Heartfield expressed in his photomontages the service the SPD provided to fascism.

“German Natural History” (1934) shows the lifecycle of a parasitic caterpillar on an oak tree. The caterpillar is Friedrich Ebert, SPD President of the Weimar Republic, the chrysalis is Paul von Hindenburg, and the Death’s Head Moth is Hitler.

His first piece for the KPD weekly Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung (Workers Illustrated Magazine, AIZ) was, “Whoever Reads Bourgeois Newspapers Becomes Blind and Deaf” (1930), in which a man’s head is wrapped in Vorwärts, the SPD’s paper. A bitter poem on the image begins, “I am a cabbage-head”.

Later, after Hitler’s coming to power and the flight of the left artists from Germany, when the Stalinists moved towards Popular Front governments in coalition with “liberal” sections of the ruling class, Heartfield provided support for this devastating betrayal of the international working class. “Look to Spain and France!” (1936), for example, brings to mind the bloody betrayal of the Spanish Revolution. Heartfield’s montages of this period follow the Stalinist line that Franco was victorious because Western imperialist powers failed to arm the Republicans, rather than because the Stalinists had betrayed the Spanish working class.

Heartfield’s courage and determination are beyond doubt, as is the strength of his best work. He continued to look to the international working class throughout this period (for example in 1938’s “China Awakes: Woe to the Invader!”), even though the political line of the KPD offered them no revolutionary perspective.

Even his later works, produced under mounting political pressure, have power in them. In “This is the Salvation They Bring” (1938), for example, bombers’ vapour trails turn into an upraised fascist salute, and the montage contains an official Nazi text enthusing about urban bombardment as a means of destroying the lumpenproletariat.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Heartfield left for Prague, where he continued to produce work for AIZ. His caricatures of the fascists provoked Czech-German tensions, but he decided [wisely] not to move to Moscow. Amid threats that diplomatic relations would be broken off, some of his works were removed from an exhibition in 1937. Fearing German occupation, he left for London in 1938.

Wieland followed shortly afterward, but was refused residence to Britain and moved to America. After the war both brothers returned to Stalinist East Germany. Heartfield’s return was facilitated by the intervention of Wieland and Brecht. As “Western emigrants” were suspected of treason, or perhaps political unorthodoxy (i.e., anti-Stalinism), Heartfield was viewed with suspicion. In 1954, however, Brecht and novelist Stefan Heym called for public recognition of his work. Two years later Heartfield was elected to full membership of the German Academy of Art and his party membership was treated as uninterrupted, meaning that from then until his death in 1968, he had official recognition.

For more information about the artist, including personal photos, writings, and recollections, please visit the John Heartfield Internet Archive.

Many thanks to John Heartfield for permission to use the images from his collection in this article.