A drought-stricken cornfield

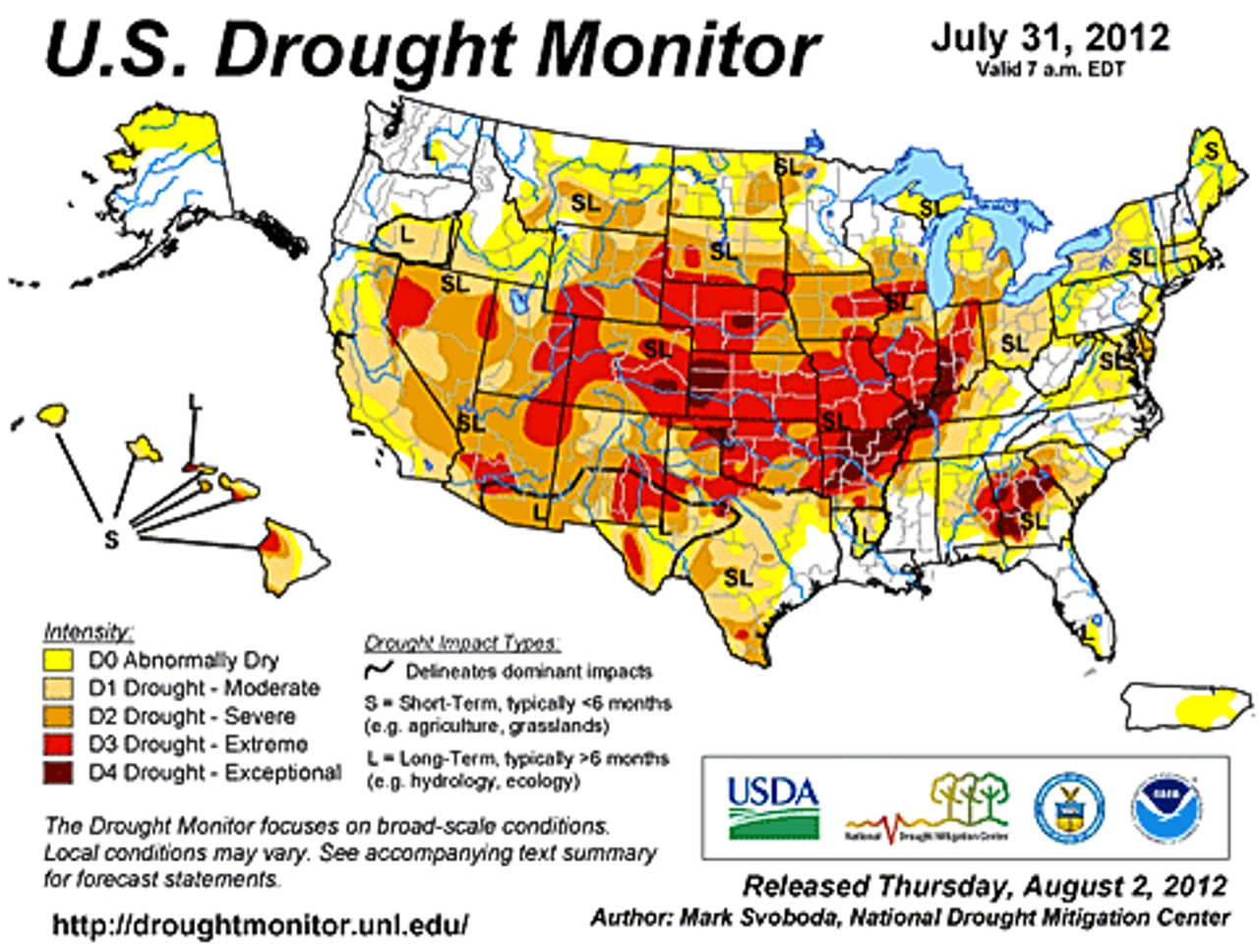

A drought-stricken cornfieldThe National Drought Mitigation Center on Thursday rated more than a fifth of the contiguous United States as in “extreme” or “exceptional” drought. The dry spell, coupled with the hottest year on record, threatens widespread crop failures in the world’s largest agricultural producer.

Nearly 40 million acres of corn are withering in the most severe drought in more than half a century. Nearly 9 out of every 10 acres of corn are under drought.

In the span of last week, the size of the most severely drought-stricken region jumped by more than 30 million acres. The US Department of Agriculture last week added 218 counties to its list of disaster areas, now encompassing 1,584 counties in 32 states.

The USDA has compared the disaster to the drought of 1988, when the rural small farm economy all but collapsed. In terms of geographic scale, the drought is on par with 1934, one of the worst years of the Dust Bowl.

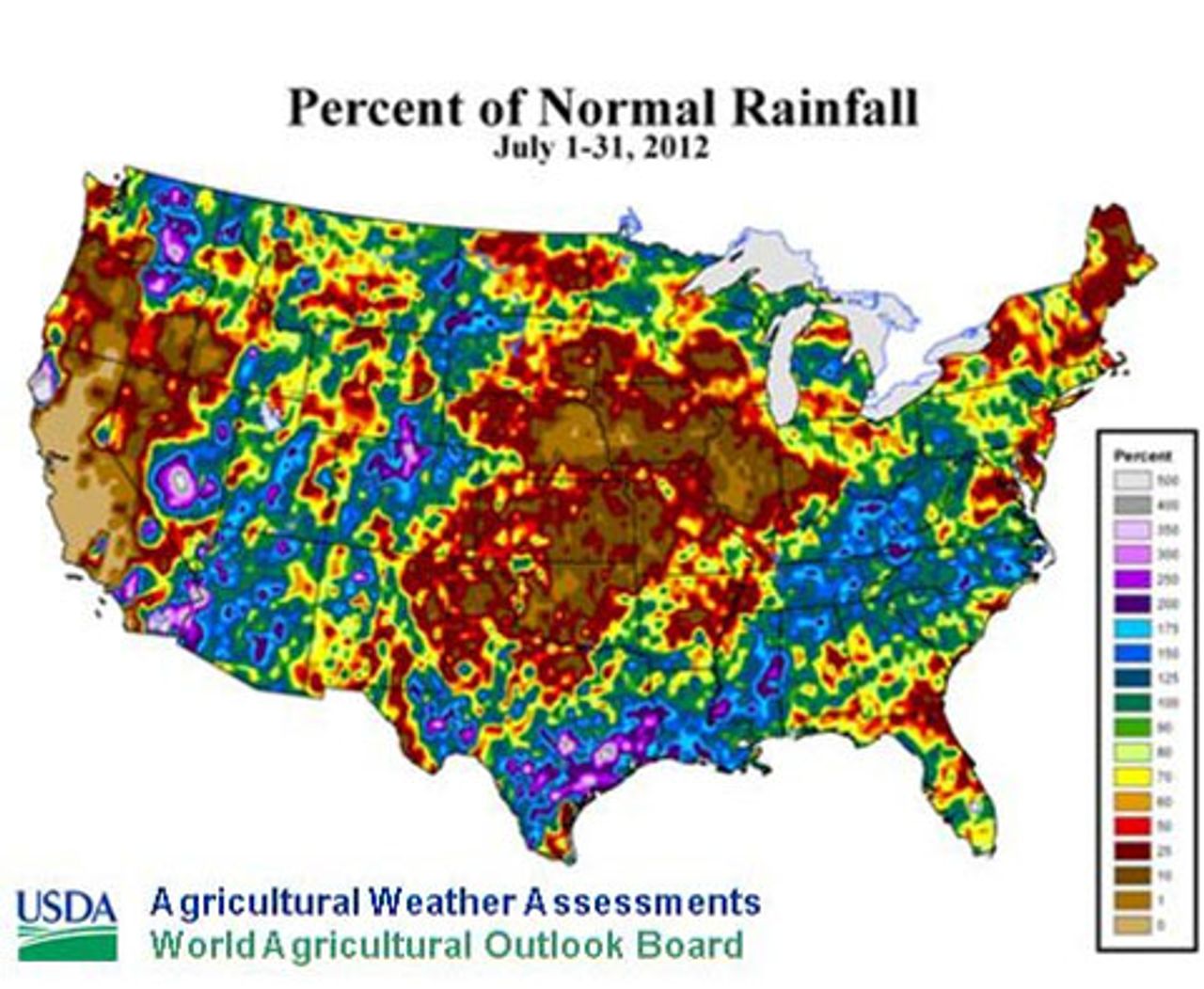

Data from the National Weather Service indicate that July rainfall was less than 50 percent of normal throughout the entire mid-section of the country. Monthly temperatures were 5 to 10°F above normal. Many areas saw all-time heat records set in 1936 or 1934 broken in July; Rockford, Illinois broke a record high set in 1921.

Data from the National Weather Service indicate that July rainfall was less than 50 percent of normal throughout the entire mid-section of the country. Monthly temperatures were 5 to 10°F above normal. Many areas saw all-time heat records set in 1936 or 1934 broken in July; Rockford, Illinois broke a record high set in 1921.

Writing for the US Drought Monitor Thursday, Mark Svoboda of the National Drought Mitigation Center (NDMC) noted that the Midwest is “impacted not only by oppressive heat, but also by depleted soil moisture, desiccated pastures and widespread crop damages, livestock culling and elevated fire risk.” The situation has created a feedback of heat and dryness, resulting in the formation of a heat dome over the region.

Heat domes, which are indicative of climate change, have had significant environmental impacts in other areas of the world recently. In Greenland, a heat dome is the suspected cause of a dramatic spike in surface melting of the region’s ice sheet in July (See: “Melting of Greenland ice sheet likely caused by global warming”).

Heat domes, which are indicative of climate change, have had significant environmental impacts in other areas of the world recently. In Greenland, a heat dome is the suspected cause of a dramatic spike in surface melting of the region’s ice sheet in July (See: “Melting of Greenland ice sheet likely caused by global warming”).

Speaking about the situation in the US Great Plains, Svoboda observed that the region “can’t seem to shake off last year’s drought,” having “now been dragged back into it this year.”

“In addition to the large geographic footprint of this year’s drought,” he added, “the quick onset and rapid ramping up of intensity, coupled with extreme temperatures and subsequent impacts, has really left an imprint on those affected and has set this drought apart from anything we have seen at this scale over the past several decades.”

Many livestock ranchers, confronted by barren grazing land and exorbitant fodder prices, are left little choice but to liquidate their herds. While grain producers have federal insurance against crop failure, ranchers do not. The USDA’s livestock insurance program was allowed to expire last year.

According to USDA figures, the nation’s cattle herd stands at 97.8 million, which is the lowest headcount since it began keeping records on cattle in 1973. Because cows take several years to raise to market, many ranchers are sending off calves early to the slaughterhouses in anticipation that the crisis will be an extended one.

Warning of higher consumer prices, the livestock industry has called for the Obama administration to suspend the federal renewable fuel standard. The mandate essentially guarantees 40 percent of the US corn crop to ethanol fuel producers, which is contributing to tight feed supplies and high stock prices.

Prices on the Chicago Board of Trade continue to rise on the poor crop news, both in the US and in other critical growing regions worldwide. Soybeans have risen 34 percent, to $16.13 a bushel; corn is up 23 percent for the year, at $7.92 a bushel. A survey of commodities analysts by Bloomberg News found most expect corn prices to continue to grow. “Hedge funds are holding the biggest bet on higher corn prices since September and almost the largest wager on costlier soybeans since at least 2006,” the news service noted citing federal data.

The World Bank and other organizations have cautioned that speculation could produce shortages in import-dependent countries and popular unrest like that of the food crisis of 2008.

The Economic Research Service, which tracks food insecurity in developing countries, has estimated that more than 800 million people will not receive adequate food in 2012, and that the world’s hungry will rise by 37 million in the coming years.

On Friday, USDA chief economist Joseph Glauber issued a statement in Beijing warning that China would face higher soybean prices. Since June, soybean prices have risen 23 percent. “We will see how bad the yields are next week when we put out our first survey-based estimate, but it looks very bad,” he said. “There is no question that yields will be very low.” China is the world’s largest importer of soybeans.

Countries dependent on imported staple crops are most at risk for price shocks. Egypt, the world’s top wheat importer, is particularly vulnerable to a poor corn crop in the US; when corn production falls in the US, American buyers increase their purchases of wheat as a substitute. As a result, there is less wheat available for export from the US, which pushes up global wheat prices. The world’s other wheat-producing regions—including Russia, Canada, and Australia—are all stricken by weather disasters like the US.

Andrei Sizov, head of the agricultural consulting firm SovEcon and newly appointed head of the Russian Food Security Commission, estimated this week that the Russian wheat harvest would not exceed 80 million tons. The Institute for Agricultural Market Studies puts the harvest at only 77 million tons. The country generally consumes 72 million tons domestically.

The slim margin of excess grain has raised the possibility of an export ban. In 2010, Russia imposed a ban after its wheat crop sustained heavy drought and wildfire damage. The decision, which tightened supply and fed a speculative rally on grain markets, contributed to social upheavals in the Middle East, culminating in the Egyptian uprising of February 2011.

In spite of the risk of renewed social explosions, as well as new restrictions by the World Trade Organization on export bans, Food Security Commission head Sirov told the Moscow News, “If the government decides that Russia needs to restrict its exports, they will find measures to do that. It could say, for example, that it is a matter of food security. Ukraine has restricted its exports and it is a WTO member.” Russia is due to enter the WTO next month.

A major drought is also tightening its grip on India. On Thursday, the government confirmed that monsoon rains are likely to be far below average. Halfway through the rainy season, precipitation is 20 percent below average. In 2009, India saw 23 percent below average rainfall and a consequent spike in food prices.