Directed by Christopher Nolan, screenplay by Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan, story by Christopher Nolan and David S. Goyer

The Dark Knight Rises

The Dark Knight RisesThe Dark Knight Rises is the most conservative and rightwing of Christopher Nolan’s PG-13 Batman films to date. This 164-minute pulp-noir superhero action thriller openly defends plutocracy, associates the working class with violent murderers and thugs, identifies revolution with terrorism and suggests that the only way to advance the social welfare is through the philanthropy of the super rich.

Why should such a film be made in the present period of world capitalist economic crisis and rising unemployment, the mass upsurge in North Africa and the Middle East, the radicalization of the American working class and the global assertion of US militarism—if not in an effort to stupefy mass consciousness? Considering that DC Comics has done projects for the US Department of State, it is a question well worth asking.

Moreover, the Dark Knight Rises appears in a socially malignant context in America today, where there is an alarming decay in cultural life and formal democratic institutions, resulting in social pathologies that too often manifest themselves in violent forms. The reality was tragically confirmed in the shooting massacre at a July premiere of Nolan’s film at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, the alleged gunman identifying with a Batman villain.

While commercial cinema is not the root of social problems, films do affect people. Under the present social conditions, psychologically vulnerable individuals will not be helped by the murky and necropohilic fantasy of the “Nolanverse,” which inherits the brutalization of the Batman comic books in the 1970s and, especially, the 1980s.

What does one feel when watching Nolan? Altogether, it is an aesthetically one-sided and emotionally distorting encounter—condescending, cruel, misanthropic, ugly and unreal—in short, much like the feeling of Batman comic books in the 1980s by writers such as Frank Miller, Alan Moore, and John Wagner and Alan Grant. Catharsis, power fantasy, wish fulfillment, perhaps this is the allure of the pulp-noir action thriller.

With a convoluted storyline, flat characters and special effects, the Dark Knight Rises is built around the complication of Miranda Tate (Marion Cotillard), a wealthy investor who works her way into the financially struggling Wayne Enterprises of billionaire Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale). Winning Wayne’s trust and intimacy, Tate is really the vengeful daughter of Ra’s al Ghul (Liam Neeson), whose death Wayne/Batman is responsible for.

Tate conceals her true identity and blood vengeance for the better part of the film, while the focus is on her henchman Bane (Tom Hardy), a bald, mysterious, muscle-bound, muzzle-wearing megalomaniac with a terrorist army, who takes Gotham City and its 12 million residents hostage. And Bane’s, Tate’s, plan? They seek the destruction of the city and the people in a nuclear blast, “the next era of Western civilization,” in Bane’s words.

Tom Hardy as Bane

Tom Hardy as BaneSince the point is for Wayne/Batman to feel failure, Bane breaks Batman’s back and casts him in a remote, underground prison with a TV set so that the he can suffer emotionally. “I fear dying in here while my city burns,” Wayne says. He recovers, exercises and escapes; confronts Bane and Tate, who die; explodes the bomb over Gotham Bay; and all assuming Batman deceased in heroic self-sacrifice, the elite unveil a statue honoring him.

As this is vacuous, the plot has fillers: Commissioner James Gordon (Gary Oldman), Batman’s ally, hides a troubling secret; Deputy Commissioner Peter Foley (Matthew Modine) wants to arrest Batman; Detective John Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) is tired of police rules; Selina Kyle (Anne Hathaway), a jewel thief, is used by Bane; and Alfred Pennyworth (Michael Caine), Batman’s butler, agonizes over the vigilante lifestyle.

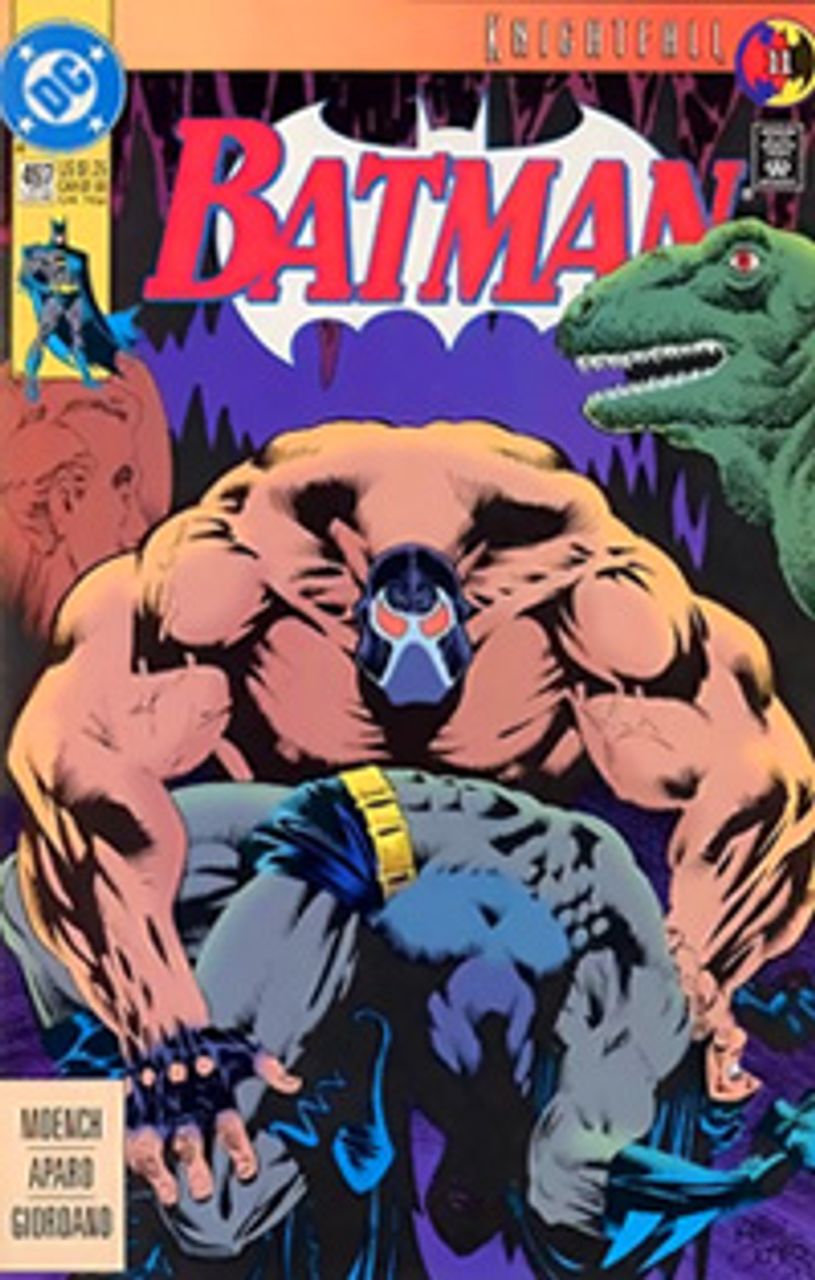

Batman, Vol. 1, No. 497, July 1993

Batman, Vol. 1, No. 497, July 1993 Clearly, Nolan knew that the Dark Knight Rises would not get far without melodramatics, not to mention superficial scene adaptations and quotes from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities (1859). But while the film has nothing at all in common with Dickens’ historical novel, written as a witness to the French Revolution of 1789, Nolan has apparently intended a publicist film statement against social revolution.

Significantly, the word “revolution” is mentioned twice in the Dark Knight Rises, and in one of these cases, it is explicitly referred to as “Bane’s revolution” by WayneTech Enterprises CEO Lucius Fox (Morgan Freeman). Besides the fact that the fictional corporation does military projects for the US Defense Department, Nolan conveys the anti-revolutionary statement with allegorical symbolism, in the maniacal character Bane.

Bane, to be sure, is an allegorical character—a personified abstraction. His name means “a cause of great distress or annoyance,” and he is a figure in whom are embodied many ideologically distorted and confused notions of what a revolution is and how a revolution is carried out. As his murderous characterization bespeaks, Bane stands for the idea that a revolution is made by the will of a terrorist-psychopath. Consider some of his words:

* “I’m Gotham’s reckoning.”

* “I’m necessary evil.”

* “I am the League of Shadows [i.e., Ra’s al Ghul’s criminal organization].”

* “I’m here to fulfill Ra’s al Ghul’s destiny.”

* “I was born in the dark, molded by it.”

* “The shadows betray you [Batman] because they belong to me.”

* “This … this [nuclear bomb] is the instrument of your liberation.”

* “We come here not as conquerors, but as liberators to return this city to the people.”

* “Behind you lies a symbol of oppression [i.e., Blackgate Prison].”

What happens in Gotham after Bane’s hostile take over? He orders people to stay in their homes; he unlocks the prisons; he summons an army of the underprivileged; he incites mass lootings and physical attacks against the wealthy; and he permits mob courts in which the rich are sentenced to “exile or death,” either way resulting in a brutal death. And all this happens while 3,000 police officers are trapped under the city streets.

Watching this film, one is presented with things in a way as to become really fearful of the terrorist “revolution” and sympathetic to the persecuted upper class and police authority, whatever their moral defects or bureaucratic shortsightedness. The impression is also created that the crisis caused by the megalomaniac Bane would not have happened had the elites, police and masses put more belief, faith and trust in Batman and been more charitable.

Thus, after Batman returns and the police are liberated, those who once mistrusted the superhero vigilante, such as Foley, see the error of their ways and fight heroically to the death against the terrorist-psychopath and his army of killers. The social distortion is incredible, but a message comes through—“Bane’s revolution” is evil, and Batman is good. It is a cheap combination of political propaganda and product marketing.

Confronted with a work such as The Dark Knight Rises, with all its artistic and social falseness and pseudo-gravitas, one really must ask the question: What is a social revolution? Unlike the confused and misrepresented allegories in Nolan’s film, a revolution is not anarchy; a revolution is not bloodlust; and a revolution is not terrorism.

A revolution involves the build up of living political energy in masses of people under the conditions of social inequality and economic oppression. Compelled by these conditions, the working population self-organizes and, guided by a revolutionary party, abolishes the profit system and establishes genuine democracy. But the revolution does not end there. It continues until all workers end repression entirely and create a world socialist society based on satisfying human needs.

Maybe a superhero film can be made that addresses real social life with some degree of honesty. So far, however, the genre has been dubious and reverential of the status quo, to the point of artistic deceit. That said, The Dark Knight Rises marks the finale of a trilogy that included Batman Begins in 2005 and The Dark Knight in 2008; yet plans are now underway for a reboot. It is unlikely that things will be getting any better anytime soon.

The author also recommends:

Over his head

[29 June 2005]

The Dark Knight: Striving to be impressive, but essentially empty

[25 July 2008]

Aurora, Colorado tragedy: The latest mass shooting in the US

[21 July 2012]

The Aurora massacre: Once again, evasions rather than explanations

[23 July 2012]