This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Argentine coup attempt provokes popular opposition

Demonstration against the military in

Demonstration against the military inBuenos Aires, April 1987

On Sunday, April 12, 1987, the so-called “Easter rebellion” revolt of the Argentine military ended after five days without toppling civilian rule. The coup attempt was led by the torturers and murderers of the nation’s 8-year “dirty war,” during which as many as 30,000 workers and students were “disappeared.”

The military rebellion began April 8 when Maj. Ernesto Barreiro, an Air Force officer who served as the chief torturer at the La Perla concentration camp under the military dictatorship, refused to observe a subpoena from the civilian courts to answer to charges of torture and murder. When Barreiro took refuge in a paratrooper base in the central city of Cordoba, he was joined by 130 officers and soldiers, who then demanded amnesty for crimes committed during the dirty war. Other military bases were seized, including the infantry school at Campo de Mayo, where fortifications were set in place with tanks and machine guns.

President Raul Alfonsin, who headed the first civilian government after military rule ended in 1983, intervened to defuse the situation on terms favorable to the military through an “act of democratic compromise” signed by all major parties. Alfonsin was less concerned with the Army than he was with the working class, which had met the attempted coup with a massive response.

Immediately after the attempted coup, thousands of workers took to the streets, driving Barreiro out of Cordoba. On April 12, hundreds of thousands demonstrated in Buenos Aires against the military. When Alfonsin, addressing the crowd, characterized the fascist officers as the “heroes of the Malvinas war” he was met with jeers and catcalls.

50 years ago: Kennedy showdown with US Steel

Kennedy with the Shah of Iran during US Steel duel

Kennedy with the Shah of Iran during US Steel duelThis week in 1962, the US media was consumed with a highly public duel between the Kennedy administration and the nation’s largest steelmaker, US Steel, over pricing and the risk of inflation. Editorial boards across the country weighed in. The New York Times, which sided with Kennedy, produced nearly 50 articles on the dispute in less than a week.

On April 10, 1962, US Steel announced a $6 per ton, or 3.5 percent, price increase for steel. It was quickly followed by other major steel concerns, including Bethlehem Steel. President John F. Kennedy immediately condemned the price increase and marshaled the authority of his office to challenge it.

On April 12, Attorney General Robert Kennedy announced a grand jury investigation into the price increase under the Sherman Antitrust Act and subpoenaed documents from the steelmaker. Privately, Kennedy prevailed on smaller steelmakers Inland Steel and Kaiser Steel to hold their prices to existing levels with promises of lucrative defense contracts. Having broken the steelmakers’ ranks, one by one the major concerns rescinded their price increases, culminating in an April 13 back-down by US Steel CEO Roger Blough.

The dispute was reported in the media as a major political victory for Kennedy, but more was at stake than political posturing. Underlying the dispute were fears over what was called the “price-wage spiral.” Months earlier, Kennedy had intervened in negotiations between US Steel and the United Steelworkers union, helping to secure a “non-inflationary” contract that essentially froze workers’ wages. The quid pro quo was that steelmakers would not raise prices. When they did so, Kennedy deemed it a “double cross.”

Kennedy feared the steel price increase could set off a new nationwide strike by steelworkers only two years after the massive 1959 steel strike. Wage and price increases in steel, the nation’s third-largest industry, would radiate outwards to all other sectors of the economy, particularly to the nation’s largest industry, auto production. Like steelmaking, the auto industry was centered in the industrial Midwest. Rising prices would accelerate the decline in US industrial competitiveness and the narrowing of the nation’s balance of payments surplus, processes that were already becoming evident.

75 years ago: Opening of the Dewey Commission on Moscow accusations against Trotsky

Trotsky

TrotskyThe Commission of Inquiry into the Charges Made Against Leon Trotsky, otherwise known as the Dewey Commission, opened on April 10, 1937 at the home of the exiled leader of the Russian Revolution in Coyoacan, Mexico. The hearings began at 10 a.m. amidst heavy security arrangements and doubled guards. In the days leading up to the opening of the proceedings, Mexico City had once again been plastered with anti-Trotsky posters by Mexican Stalinists.

The commission sat at a wooden table at the head of the room. At the center was the chairman, John Dewey, the eminent American philosopher and educator. Under immense pressure directed from Moscow, Dewey was forced to break old friendships with liberal friends to see through his desire to chair the commission. Alongside Dewey was commission secretary Suzanne La Follette of the famed Wisconsin political family, Carleton Beals, an expert on South America, Benjamin Stolberg, a labor journalist, and Otto Ruhle, a former communist member of the German Reichstag and biographer of Karl Marx.

At a separate table to the left of the commission sat a court reporter with legal advisers on either side of him—John Finerty, the counsel for the commission, who had previously argued on behalf of Sacco and Vanzetti, and Albert Goldman, a Trotskyist and lawyer, who represented Trotsky.

At another table sat Trotsky, his wife Natalia, and Trotsky’s secretaries. Members of the international press took up approximately half the public seats, with the other half occupied by representatives of local labor organizations. Large numbers of people were turned away throughout the proceedings.

The commission had invited representatives from the Soviet Union and both the American and Mexican Communist parties to present evidence and cross-examine the defendant. They declined or failed to respond.

Over the course of eight days, Trotsky meticulously exposed and refuted the accusations cooked up by the Stalin murder machine. “There was not a single question into which he refused to go or which he dodged,” wrote Trotsky biographer Isaac Deutscher. The charges of collaboration with fascist and imperialist powers, industrial “wrecking,” and advocating the restoration of capitalism in the Soviet Union fell to pieces. Trotsky exposed Stalin’s treachery and his nationalist falsification of Marxism, while defending the Bolshevik seizure of power and his own leadership role in the Russian revolution and the early years of the Soviet Union.

100 years ago: The sinking of the Titanic

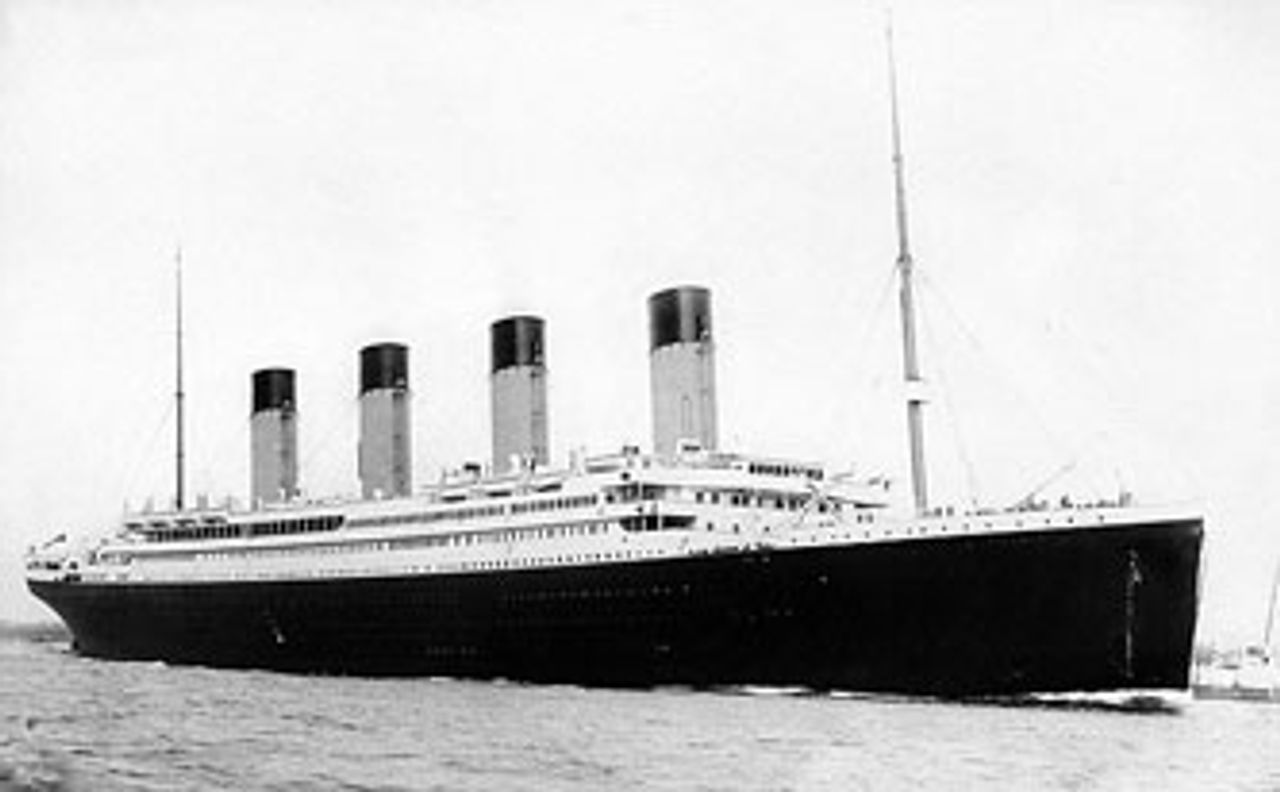

Titanic

TitanicOn April 15, 1912, the RMS Titanic sank on her maiden voyage after colliding with an iceberg in the North Atlantic Ocean. The massive ocean liner, which was the largest ship afloat when it sank, was traveling from Southampton, Great Britain to New York, and had already stopped at Cherbourg in France and Queenstown in Ireland. Of the 2,224 people on the ship, including the crew, 1,514 died.

Operated by the White Star Line, the Titanic was billed as “unsinkable.” It was designed to attract wealthy first-class passengers with libraries, a swimming pool, a gymnasium, and extravagantly furnished cabins. The Titanic was commissioned in the context of a fierce struggle between the White Star Line and its competitors such as Cunard for dominance of the lucrative cruise liner market.

First-class passengers who had use of the ship’s luxury amenities included millionaires, industrialists and socialites. Second class was largely composed of professionals and other middle-class layers, while third class overwhelmingly consisted of working class immigrants seeking work in the United States.

The Titanic carried only enough lifeboats for around half of the ship’s passengers and crew. The majority of the dead were crew members and third-class passengers. The ship’s 710 survivors reported chaotic and confused scenes when the Titanic began to sink, indicating that there had been little preparation for an emergency.

The lax safety measures and the loss of life resulted in a public outcry. Official inquiries were carried out in Britain and the United States. Both found that the scope of the disaster was a product of inadequate regulations on the number of lifeboats ships were required to carry, and that the lifeboats had not been properly filled or crewed. They also determined that failure to take proper heed of ice warnings contributed to the disaster, and that the collision was the result of the Titanic traveling into a dangerous area at too great a speed.