Directed by Sean Branney. Currently running at Theatre Banshee, in Burbank, California until May 13.

The Merchant of Venice

The Merchant of VeniceThe production of William Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice now running at Theatre Banshee in Burbank, California (part of greater Los Angeles) is vibrant and refreshing. It revels in the sheer complex humanity of the bard’s mid-career tragicomedy (written c. 1596-1598).

The company, under the deft direction of Sean Branney, brings out the youth and humor of the material in ways that, without the gimmicks of “concept staging” (setting Elizabethan dramas in Victorian England, 1950s Manhattan, or today’s Las Vegas, etc.), give the play a remarkably contemporary feel.

Portia and Bassanio, the lovers at the center of the story, are young, a bit reckless and playful, yet fully aware of their nascent adulthood. Around them lies a rat’s nest of prejudice and unsavory machinations. We all know that Shakespeare’s play is engaging and provocative, but who knew it could be so funny?

One of the first questions that an acting company asks is: Whose dramatic problem drives the narrative? With many plays, the answer is obvious, often too obvious. Not so with The Merchant of Venice.

The Merchant of Venice

The Merchant of VeniceDespite the presence of the iconic Shylock, the Jewish moneylender, often the only character that audiences remember and who attracts every great actor, the play is not called “The Moneylender of Venice.” We know from the first printed edition of the play that the titular “merchant” is Antonio, an import-export heavyweight. But there’s also merchant Bassanio, Antonio’s beloved and down-on-his luck protégé, and a gaggle of other mercantile associates. All of which points to the fact that Shakespeare’s play, written in the final years of the sixteenth century, is rooted in a world of commerce and explores the fault-lines in a community consumed with trade.

The play addresses issues that were very much on the minds of anyone living in London at the time, where a merchant class was accumulating power and influence, fueling resistance to royal authority, and reinforcing the non-conformity of a growing Puritan movement. Within a few decades, the social and economic processes would spark a revolution against the aristocratic order. In the bustling entrepot of Venice, Shakespeare found a mirror in which to examine his own city and society with particular attention to the hypocrisies of the rising merchant class.

Nearly all the action in the play is driven, directly or indirectly, by money. Ready-cash and financial cushions figure even in the play’s many love stories. In case you need a refresher, the dramatic problem that launches the action is Bassanio’s dilemma: he’s in love with the young, rich, fatherless Portia, but, because he’s penniless, he’s unable to cover the costs of a courtship and, we gather, feels unworthy to compete for her hand.

Antonio gives his young friend Bassanio the three thousand ducats he needs. But Antonio has his own cash-flow problems: all his capital is tied up in enterprises—he’s got half a dozen ships at sea, any one of which, if it comes in, will be more than enough to cover the debt he incurs by borrowing from Shylock the moneylender.

Rather than secure the loan with any of Antonio’s properties—he presumably lives someplace—Shylock asks instead for a pound of flesh. It’s an absurd bargain, but it is also a loan explicitly made without interest. One of Shylock’s complaints against Antonio is that the latter has been lending interest-free to his friends, thereby undercutting Shylock’s only source of income.

In making the deal, Shylock reminds Antonio of the many times that he, a typical Venetian bigot, has mocked, insulted and spat upon the Jewish moneylender in public. One effect of the bargain, from Shylock’s point of view, is that, at least for the three-month term of the loan, he and Antonio will be equals, deserving of mutual respect. But then, a ne’er do well Venetian swell—one of Bassanio’s associates—runs off with Jessica, widower Shylock’s only child and only family. Jessica is an enthusiastic co-conspirator, eager to escape her ghettoized world (our word “ghetto” comes from Il Ghetto, the section of Venice in which all Jews were forced to live). Not only does Jessica arrange her elopement, she also runs off with a chest of gold, and, in the cruelest cut of all to her father, agrees to convert to Christianity.

The Merchant of Venice

The Merchant of VeniceSub-plots proliferate, none more commanding than Portia’s fulfillment of her recently deceased father’s will, that she should marry whichever man can pass a test. Each suitor is presented with three chests—one gold, one silver, one lead—each with a proverb inscribed on its lid. The suitor’s choice reveals his character, and more importantly, his flaws. In the end, to Portia’s joy, Bassanio correctly picks the lead casket and wins his beloved’s hand. And Portia, to secure her new husband’s happiness, saves the day by disguising herself as a brilliant young lawyer who, at the last moment, advises the court just as it’s about to exact Antonio’s payment of that pound of flesh to be cut from his chest.

In Shakespeare’s day, the few Jews who remained in England since their expulsion in the late thirteenth century were living in the shadows, often feigning conversion; they wouldn’t be allowed to reside legally in the country until Cromwell’s revolution, some forty years later. Despite the absence of Jews, official anti-Semitism had been very much a part of English life for centuries, reinforced through religious teaching and the “Christ-killer” mystery plays that continued to be performed. Shylock’s rage expresses the weight of centuries of anti-Semitic oppression.

Debate has long raged over the play’s attitude toward Jews: is the play a prime example of Christian anti-Semitism or is it, in fact, a critique of bigotry and prejudice? The play has been interpreted and played both ways. How the play is seen depends on how Shylock is presented. Until the nineteenth century, Shylock had been presented as a grotesque caricature, a repugnant “other” in an otherwise genteel gentile society. Christopher Marlowe’s Barabas in The Jew of Malta was Shylock’s most immediate predecessor.

These days the moneylender is typically presented as an unjustly marginalized, callously victimized member of a minority whose rage is understandable, whose vengeance upon his oppressors is not only justified, but applauded. In most contemporary productions, as this one does so well, Shylock “holds a mirror” up to the hypocrisies of the gentile merchant class and exposes the bias in their fetishized legal codes. In these new interpretations, Shylock’s forced religious conversion feels like a tragic deracination and the forced forfeiture of his wealth feels like the triumph of a ruling class crushing yet another outsider.

In a sense, both representations, although the latter is certainly more humane, are somewhat ahistorical. The question, “Was Shakespeare an anti-Semite or not?,” has a limited value. Did Shakespeare share the views and prejudices about Jews, historically shaped and determined, of most of his English contemporaries? Perhaps. But Shakespeare was the greatest playwright in history, among other reasons, because he was able to put himself in anyone’s shoes, and see the logic of everyone’s actions. However the playwright may have conceived of Shylock as he began his work, he felt obliged at certain moments—as an immensely honest and objective artist—to take the moneylender’s side, so to speak.

Thus, in Shylock’s famous soliloquy, we encounter one of the most compassionate and brutally frank speeches in world literature: “Hath not a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal’d by the same means, warm’d and cool’d by the same winter and summer as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.” (Act III, scene I)

Kirsten Kollender’s Portia is a very pretty, high-spirited, extremely clever “girl”; her interplay with her two equally young maids-in-waiting has the sly energy of three girls on spring break, looking for the perfect match-up, but without ignoring the earnestness of young women who understand the seriousness of making a marriage match. Daniel Kaemon’s Bassanio is such a paragon of manly sensitivity that we fully understand why Portia so desperately wants him and why we’re rooting for him to pick the right casket to win her hand—even though the play’s formula makes the happy choice feel almost predetermined. As Antonio, Time Winters delivers a complex man of subdued, possibly repressed passions.

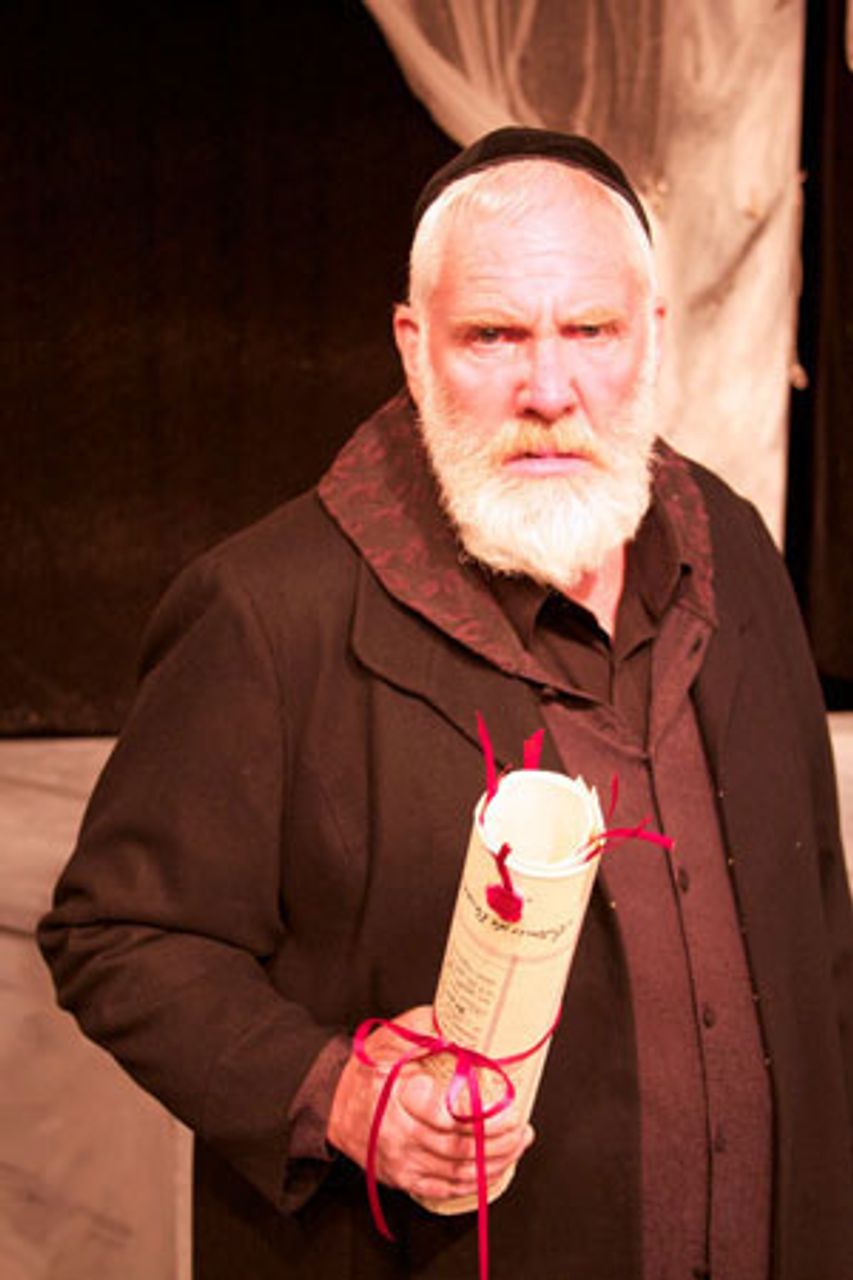

The homosexual overtones in the Antonio-Bassanio relationship, overstated in some productions, are masked here in what feels like a genuine mentor-protégé, almost paternal-filial connection, which neatly contrasts with Shylock’s smothering relations with his daughter. Barry Lynch’s Shylock is a work of dazzling substance, capturing the pride, the pain, the tenacity and the human flaws of this signature role.

Across the board, the acting ensemble, especially Ericka Winterrowd’s Nerissa, Anthony Mark Barrow’s Prince of Morocco and Brett Mack’s Gratiano, is stellar. Reber Clark’s impressive symphonic score adds heft to a production that might strike some as too intent on the comedy. But ultimately, having been opened up by laughter, it is the gripping drama of justice, the often brutal ways in which society’s winners and losers are determined, that moves us.

More than anything, the Banshee’s production of this classic “problem” play demonstrates just how timely and relevant a supposedly too familiar play can be when handled with verve and intelligence. Director Sean Branney has done a superb job with stage compositions that always enhance the lives and relationships of not just the major characters, but the often overlooked supporting ones as well.