An exhibition at the New Museum, New York City, July-September 2011

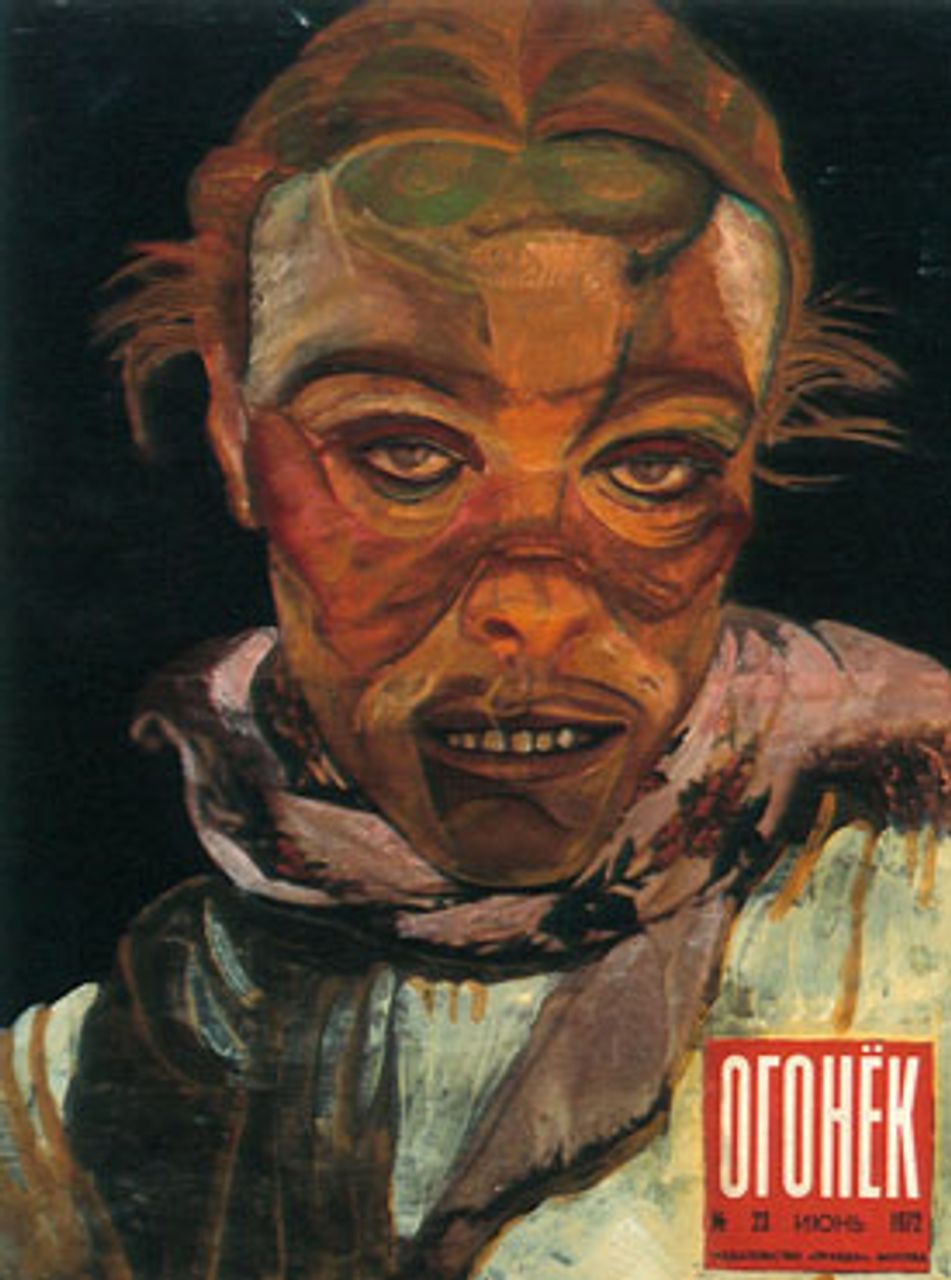

Sergey Zarva, Untitled, from the “Ogonyok”

Sergey Zarva, Untitled, from the “Ogonyok” series, 2001.

An exhibition entitled “Ostalgia” at the New Museum in New York City this past summer brought together the work of over 50 artists from the former Soviet Union and Stalinist Eastern bloc countries organized on the premise there exists a certain nostalgia for the period before the restoration of capitalism in these areas. (The show’s title is a neologism of the words “nostalgia” and “ost”, or east.) The show included paintings, sculpture, prints, photography, conceptual installations and a good deal of video produced in the period from prior to the dissolution of the USSR in 1991 to the present day.

Even though some of the work fell short of being fully satisfying as art, it was almost always interesting and unfamiliar, at least to Western audiences. The fact that these artists and their work should be so little known only underscored the enduring damage of both Stalinism and anticommunism to cultural consciousness.

Moreover, the way in which the former Soviet Union and Eastern bloc were reintegrated into the world economy—not through a political revolution by the working class against the sclerotic Stalinist regimes, but through the restoration of capitalism by elements within the bureaucracy itself—has caused its own serious damage.

A good many of the artists in their work and statements question the re-imposition of market relations and the economic inequality inherent in capitalism, and the unhealthy effect this has had on art, no less than on everyday life. Although marked by an understandable degree of confusion, the artwork in the exhibit in a variety of ways expressed not simply a rejection of Stalinism, but also a critical attitude toward what has replaced it.

Although not arranged chronologically, the artwork in the show could roughly be divided into three sections: that which was produced from the 1960s to the 1980s; a second group of works either produced during, or that reflects directly on, the period of “perestroika” in the late 1980s-early 1990s; and a third grouping that expresses experiences of life in the former Soviet Union/Eastern bloc since the restoration of capitalism.

The artwork from the 1960s and 1970s was arguably the most interesting of the exhibition, as it often included original video footage and photographs providing a glimpse into Soviet daily life in a bygone era. At the time, at least according to the propaganda in the West, people in the USSR and Eastern Europe might as well have been living on the far side of the moon, so completely alien, or at least miserable was their existence supposed to be. Life under “communism” was said to be nothing but scarcity of consumer goods and political oppression.

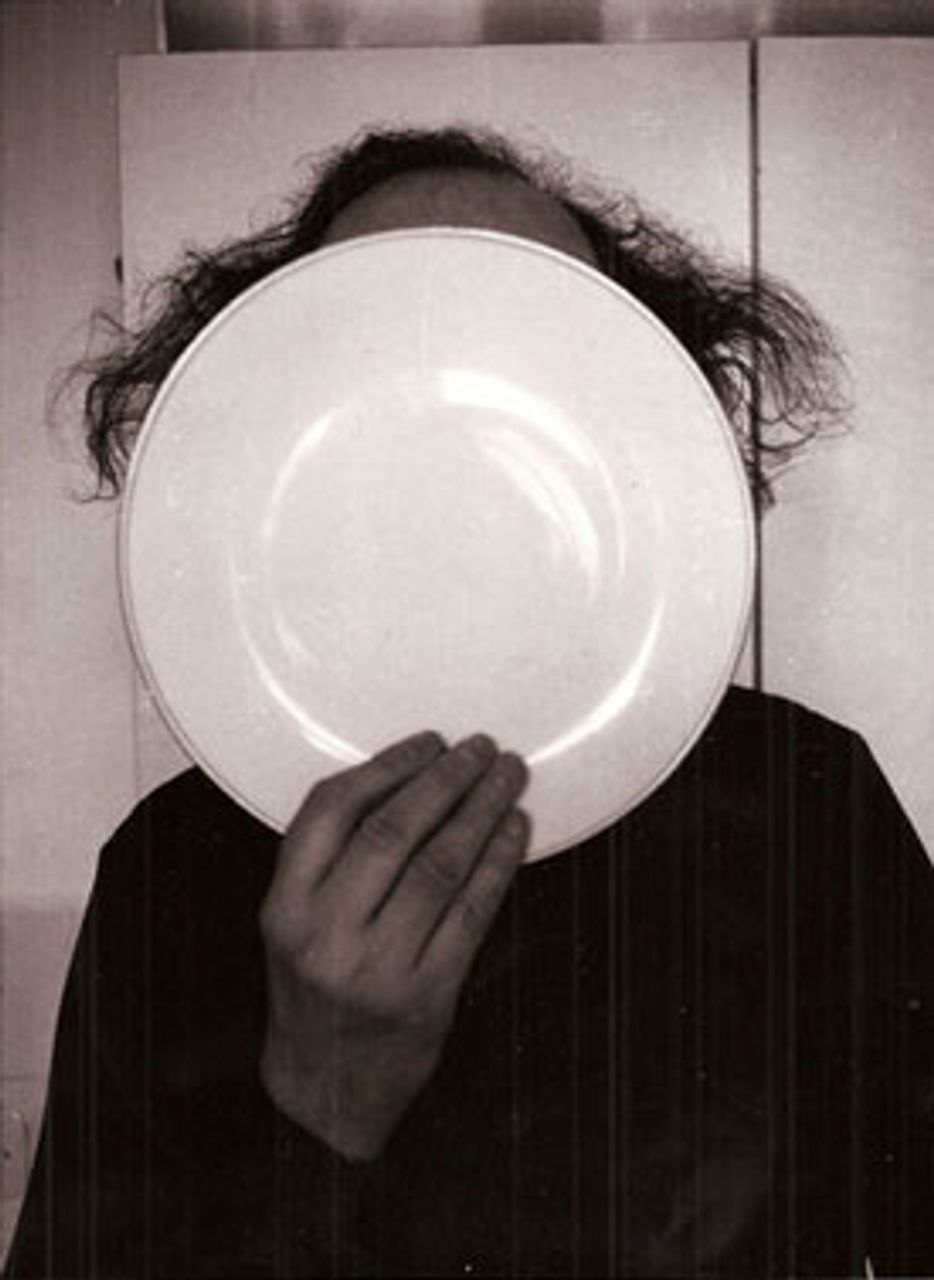

Julius Koller, U.F.O.-NAUT J.K. a (U.F.O.), 1987.

Julius Koller, U.F.O.-NAUT J.K. a (U.F.O.), 1987.While both these elements of life existed, the response of citizens in the Stalinist countries, at least as expressed by these artists, was not as simplistic or one-dimensional as anti-communism would have it be. Certainly there is a strong reaction against the conformity demanded by the Stalinist regimes, even after the so-called “thaw” of the Khrushchev period in the 1950s.

Although not subjected to the same degree of persecution as an earlier generation of “dissident” artists who often paid a heavy price for pursuing their artistic vision independent of official Soviet cultural channels—including disenfranchisement, and even in some cases exile and death—artists continued to make efforts in their work to break through the fabric of official lies told about the conditions of life, and overcome the isolation that this imposed.

Tibor Hajas’ 1976 video Self Fashion Show with its succession of people of all ages and types was at once an update of early 20th century German photographer August Sander’s social portraiture, and a subtle commentary on individuality within social conformity. It was also fascinating and amusing to see Soviet citizens in the 1970s dressed in much the same fashions as everywhere else.

Other work, such as the Leningrad Album of drawings by Evgenij Kozlov or the collection of photographs by Boris Mikhailov, Suzi Et Cetera, captured a different aspect of life—an intimate and mysteriously erotic world tucked away in small, cluttered apartments behind the facade of Soviet reality.

(Mikhailov’s photographic “Case Studies” of homeless people in his native Ukraine was concurrently on exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art this past summer.)

According to Mikhailov (whose work is now represented by Saatchi Gallery, the London contemporary art dealership that launched the careers of Damien Hirst and other art-market stars) “These particular images first portray the working class of the Cold War era and then the poverty-stricken public, proving that both Perestroika and Glasnost left the people of the Ukraine with much less than they promised.”

While the newly enriched Russian elite has been refurbishing the monuments of the Tsarist past, these brutal images of people covered in rags might well have been taken in the days of serfdom. One can’t help but think that the media has raised the fact that Mikhailov paid his subjects to pose in an effort to discredit the photographer for exposing the darkest side of capitalist restoration.

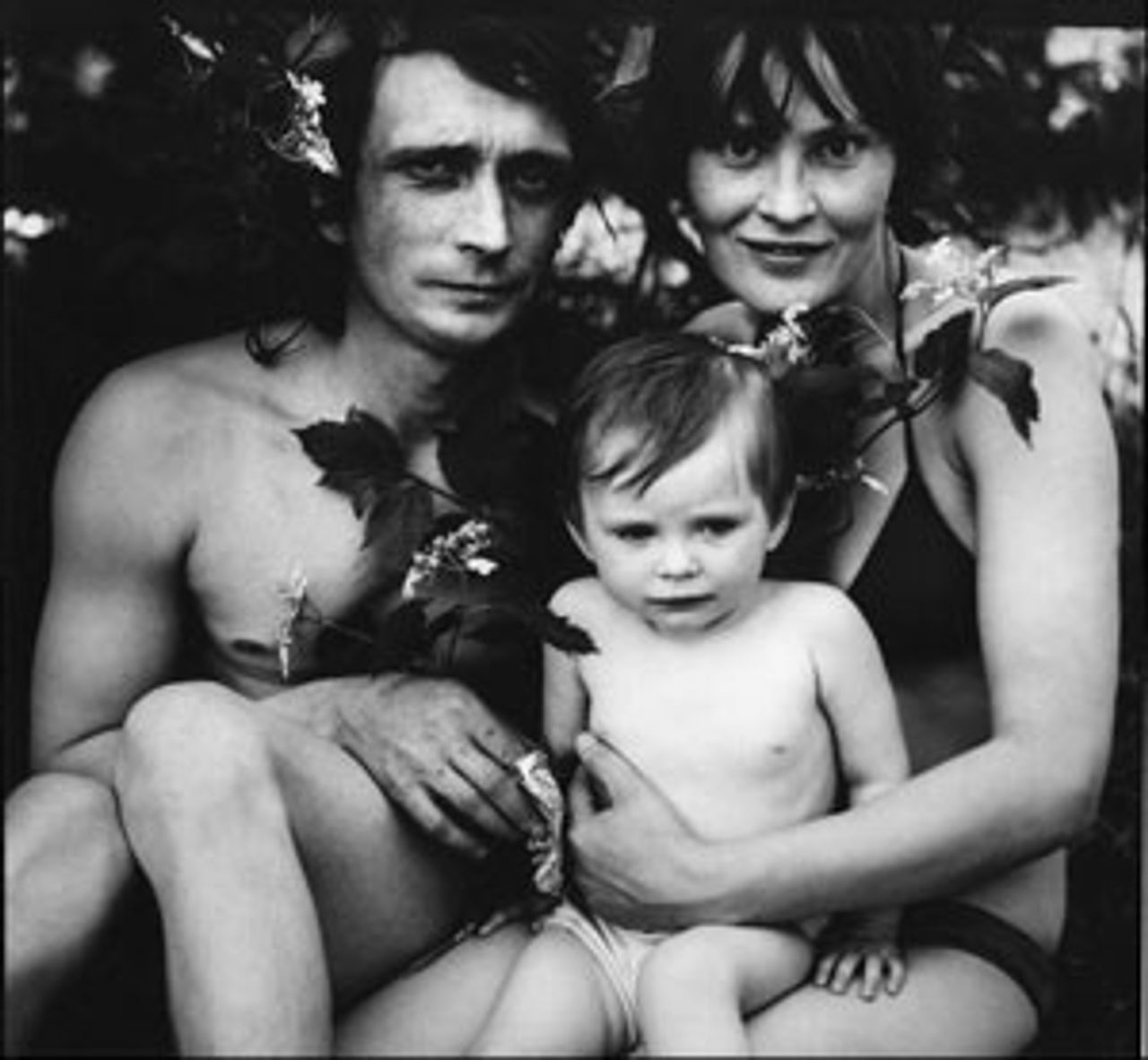

Nikolay Bakharev, #14 from the “Relationship”

Nikolay Bakharev, #14 from the “Relationship” series, 1989.

In the Ostalgia exhibit, Nikolai Bakharev’s photographs of family groups and friends on holiday, taken over a twenty-year period from the 1980s till the 2000s, were also extraordinary. Posed mostly in bathing suits amidst a dense sylvan background, these people—of all ages from infants to grandparents, groups of teenage boys, couples young and old—gaze with riveting expressions which somehow include the viewer in their intimacy, as opposed to creating a sense that she or he is a voyeur.

Similarly evolving from a tradition of “amateur” photography that was the norm in the Soviet period if one worked outside the officially sanctioned artist unions, the photographs of women factory workers in East Berlin by Helga Paris documented everyday life “as realistically and as hauntingly as possible.” As Paris explains, “the need to document everyday life in photographs developed out of necessity. In East Germany, only favorable photographs were shown in papers and to the public—ideally of the happiest people possible. Real life was hardly ever documented.”

She remains no less dedicated to clear-sighted observation since the Berlin Wall came down, recording the effects of gentrification and the growth of social inequality. “After 1989, the social gap brought about many changes which, of course, can be read in people’s faces.”

Artistic efforts concerned with the political maneuvers carried out by the Soviet bureaucracy under the banner of “perestroika” formed a second body of work in the exhibit. These works were mostly videos. While one felt most of these artists were sincere in their desire to make sense of an immense historical experience, they were nonetheless terminally hampered, through no fault of their own perhaps, by a lack of historical perspective. Certainly the effects of Stalin’s ruthless purges of Trotskyism and of any vestiges of the Left Opposition to Stalinism were felt most sharply here.

At its best, this body of work communicated a sense of its own confusion and disappointment in political “revolutions” that removed certain hated figures from power, but did not result in the kind of liberation that had been hoped for. However, post-modern discourse and radical politics, with their fixation on subjectivity and “identity” issues, had a greater presence in this work than in the photography previously discussed.

For example, Irina Botea’s video Auditions for a Revolution—filmed in 2006 in Chicago—has people reading lines from news footage of the 1989 Romanian revolution but in English in order to “outline multiple possible translations of past events.”

However, the relative absence of the influence of identity politics in much of the work in the recent exhibit was striking. The promotion of gender and ethnic background as the defining categories of human experience that has prevailed in the United States, and in slightly different forms in Western Europe with increasing intensity since the 1990s, was almost unknown in the former Soviet Union/Eastern bloc before the restoration of capitalism.

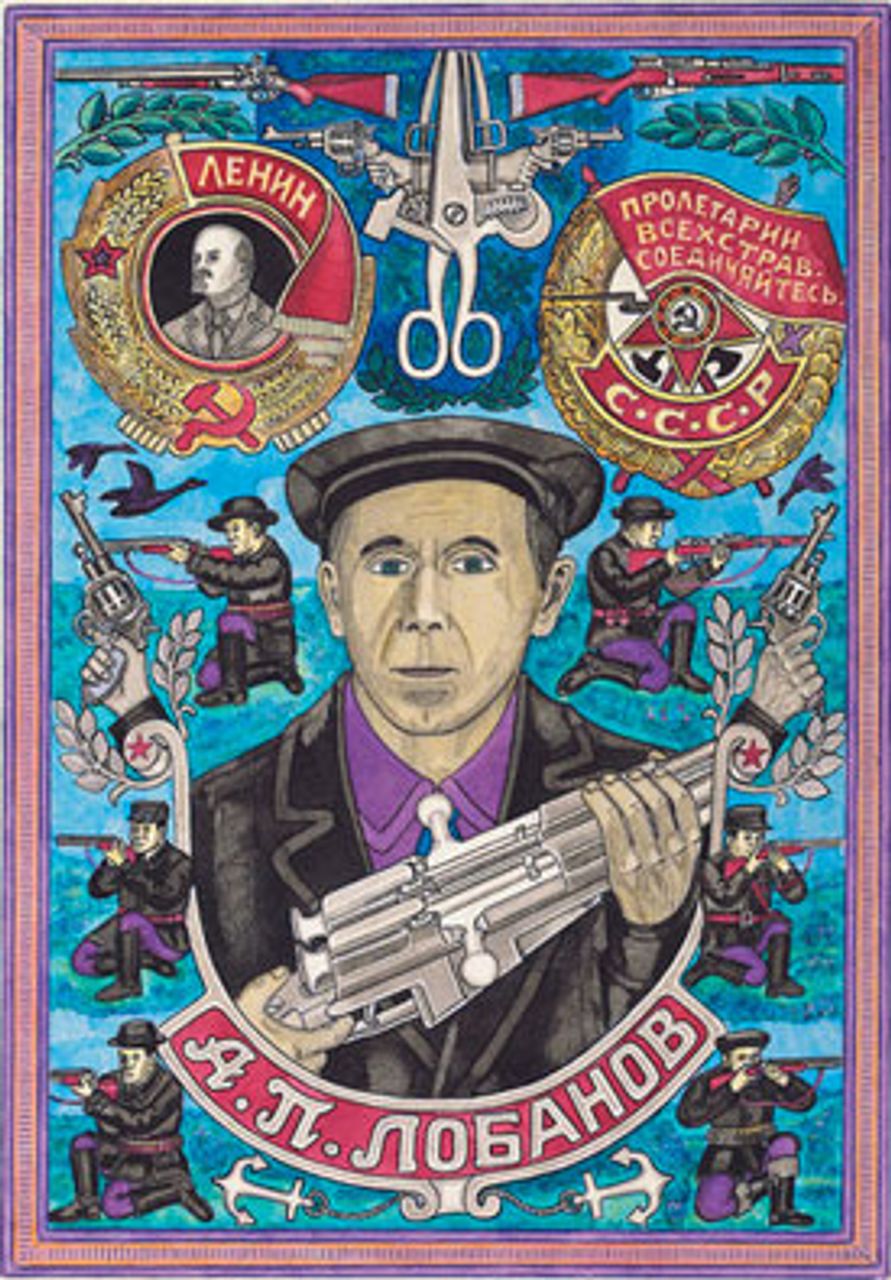

Alexander Lobanov, Untitled, ND.

Alexander Lobanov, Untitled, ND.Likewise absent was the ubiquitous pressure of the art market on the type of work that was produced, or at least brought to broader attention. Art critic and scholar Ekaterina Degot writes:

“With the advent of the art market, artists’ communities started to dissolve and the focus shifted to singular artworks, which was a painful and rarely positive process. In the 1990s, the former Communist society as a whole underwent a massive, neo-liberal brainwash. The result, at least in Russia, was an extremely unjust state capitalist system, in which art institutions represent a branch of entertainment culture for the rich rather than a necessary part of civil society.” (Catalogue, p. 52)

There was a great diversity of additional work in the exhibit that merited attention, but some pieces stood out for their powerful imagery above and beyond the political point, should there have been one. For instance in Said Atabekov’s video Sniper (2005), a mother rocks a child in a cradle with a handle made from a Kalashnikov rifle as the wind blows across the Kazakhstan steppe. In Jan Toomik’s video, Father and Son (1996) the tiny nude figure of the artist skates in a vacant snowscape.

Or in Anatoly Osmolovsky’s photograph A Voyage of Netsezudik to Brobdingnag (1993/2011), the artist perches on the shoulder of a monumental statue of the early Soviet poet Mayakovsky, like a figure out of Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels to which the title refers. More broadly, it suggests the metaphor as coined by Sir Isaac Newton, “If I have seen a little further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.”

Overall, the work in the Ostalgia exhibit was characterized by its engagement with social reality in the last decades of the Soviet Union, and the cataclysmic experience of its collapse. Whether approached through the intimacy of Bakharev’s photographs, the evolution of Constructivist aesthetics found in the sculpture/objects of Herman Glöcker, or the attempt to come to terms with historical experiences in the timeline of events by the conceptual group “Chto Delat?” (“What is to be done?”), the work in the exhibit implicitly demanded an answer to the question “Was there an alternative to Stalinism in the Soviet Union?”

This is not a question that can be answered simply by artists on the level of art—it requires political study and struggle to understand what happened to the Left Opposition led by Leon Trotsky. But that many of these artists reject the post-Soviet falsification that there was nothing to defend in the former Soviet Union reflects not a nostalgia for Stalinism for the most part, but a skepticism toward capitalism that gives their work a disturbing vitality. It is a good place to start.