The US State Department recently released its “2010 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices.” This year’s annual report provides details on human rights conditions in over 190 countries. Included are reports on the member countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), which represents the US-backed monarchies of Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Oman, Qatar and Kuwait.

This Saudi-dominated alliance backed the imposition of a no-fly zone in Libya, and has provided key support for the attack on Libya by the United States and European powers. The GCC has also provided military and police personnel to put down insurrections against the repressive regimes in Bahrain and Yemen.

While the US seeks to cloak its imperialist assault on Libya in “humanitarian” terms, its allies in the GCC are guilty of widespread violations of human rights and practice repression and torture in their own countries. This WSWS series examines these human rights abuses as documented in the State Department reports. This final installment covers the United Arab Emirates. See our previous reports on Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait and Oman.

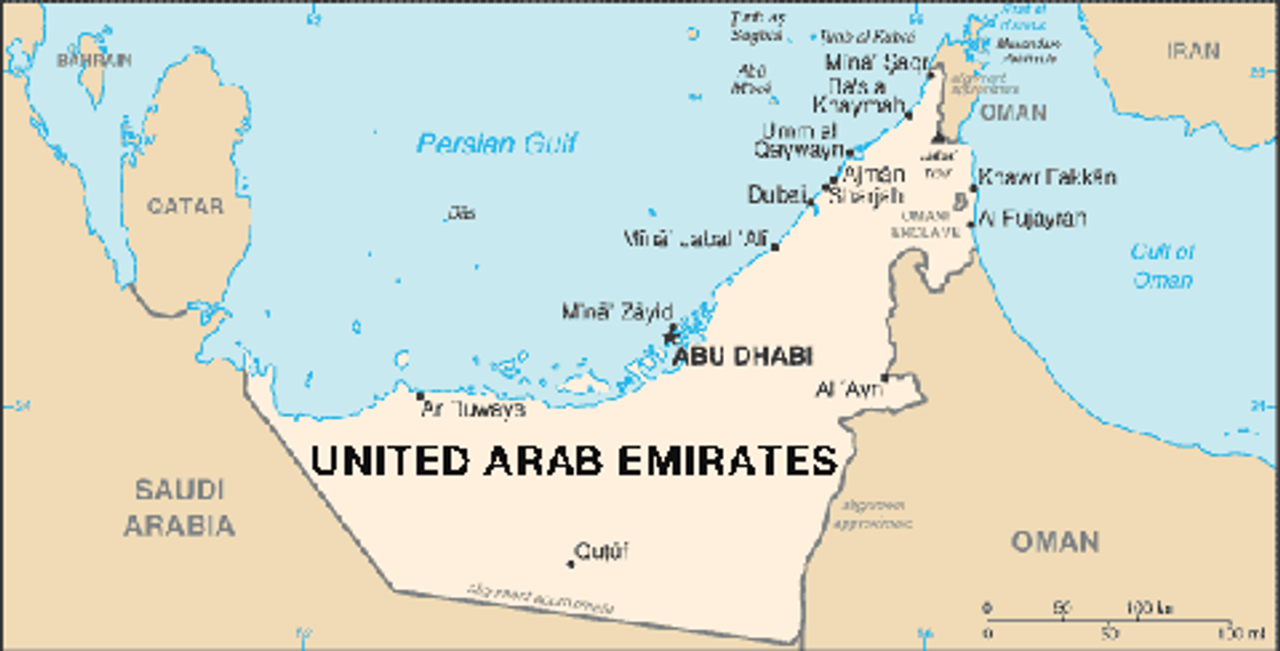

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) border Saudi Arabia and Yemen near the strategic Strait of Hormuz, and are a federation of seven semiautonomous political regions. In addition to the two most well-known—Dubai and Abu Dhabi—the emirates are Ajman, Fujairah, Ras al-Khaimah, Sharjah and Umm al-Quwain.

While the total population of the UAE is about 6 million, only about 1 million are citizens. Despite the Emirates’ vast oil wealth and a gross per capita income higher than those in many Western countries, immigrant workers are often paid poverty wages and subjected to appalling conditions.

The Emirates have a federal constitution, but citizens have no right to change the government, and the “electorate” is handpicked by the rulers themselves. The constitution is often not followed in practice.

Despite some tensions with the United States—most notably over possible military strikes on Iran and the January 2010 Mossad murder of Mahmoud al Mabhouh in Dubai—a February 2010 cable from Ambassador Richard Olson to the Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff stated that “the UAE is one of our closest partners in the Middle East and one of our most useful friends worldwide.”

Diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks detail this alliance. A July 2007 cable from then-Ambassador Michele Sisson to Defense Secretary Robert Gates talked of the UAE’s interest “in sending Emirati Special Ops troops to Afghanistan to get [its] military forces battle-hardened so they may effectively confront imported or domestic extremism” and of approving sales of Blackhawk helicopters and Patriot anti-defense missiles to the UAE.

A July 2010 cable about the airport in the small emirate of Ras al-Khaimah stated that some companies benefiting from the lack of customs fees in a nearby “Free Trade Zone” were shipping armored vehicles to Afghanistan on cargo flights.

UAE Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan met late last month with Barack Obama at the White House. An administration spokesman said the two leaders had a “productive and wide-ranging” discussion on the “common strategic interests” in the region. The UAE and Qatar are the only two Arab states to send warplanes to the US-NATO military assault on Libya.

No independent judiciary

There are no jury trials in the United Arab Emirates. Defendants are entitled to representation only after police have finished their investigation, and “police sometimes questioned the accused for weeks without access to an attorney,” according to the US State Department Report.

While the constitution prohibits arbitrary arrest and detention, this protection is often not extended to non-citizens. Moreover, “the law permits indefinite, routine, incommunicado detention without appeal,” thereby denying the basic democratic right of habeas corpus.

In January 2010 an adviser to the crown prince of Ras al Khaimah gave a television interview in which he spoke out about the lack of press freedom. The adviser was fired and his passport withheld, with no information on when it might be returned.

While there is a separate court system for civil cases, criminal and family cases are tried in Sharia courts. The State Department report notes that this system makes the burden of proof in rape cases very heavy. In October 2010, the Federal Supreme Court of the UAE upheld a husband’s “right” to punish his wife and children physically, “so long as [it] did not result in bruising.” The State Department also notes that “there were several reports that police refused to protect women if they made…complaints” of domestic abuse; “instead, police reportedly encouraged women to return home.”

The lack of an independent judiciary means that “those in power or connected to the ruling families rarely were punished for corruption.” In one high-profile case, despite video evidence of the crime, Sheikh Issa bin Zayed al Nahyan of the royal family was acquitted in January 2010 of having tortured an Afghan grain dealer with a cigarette lighter, an electric cattle prod, and a nailed board.

No right to change government

Hereditary rulers of the seven emirates form the Federal Supreme Council (FSC), which holds legislative and executive power and elects the president and vice president from among its own members. A “consultative body” called the Federal National Council has 40 members, 20 of whom are appointed by the ruling families, while the remaining 20 are chosen by an “electorate” hand-picked by the rulers. The State Department report does not explain how the emirs arrived at the number of voters—6,689—used in 2006. While women hold some positions in the FSC, they made up only 17 percent of the hand-picked voters in that year.

Political organizations, political parties, and trade unions are illegal in the UAE, and the law prohibits “speech that may create or encourage social unrest.” The State Department also reports that “official permission was required for conferences that discussed political issues,” and that news organizations practice “extensive self-censorship,” because they fear government reprisal. The UAE’s libel laws impose fines of 5 million dirhams (approximately $1.4 million) for “disparaging senior officials or royal family members.”

No independent press

The UAE government owns three newspapers and uses subsidies to influence private-sector media. Many journalists in the UAE are foreign nationals and can be deported if they run afoul of the government. The State Department reported that “the law authorizes censorship of domestic and foreign publications to remove criticism of the government, ruling families, or friendly governments.” News organizations in the Dubai Media Free Zone are able to report to the outside world without restrictions, but there is much censorship within the UAE.

The president appoints a National Media Council that censors all publications—including those put out by private associations—and has responsibility for blocking websites the government dislikes.

Censorship extends into the schools, where “the government prohibited students from reading texts featuring sexuality or pictures of the human body including in health and biology classes.”

Lack of workers’ rights

Unions are illegal in the United Arab Emirates. While workers are allowed to collectively file “employment dispute complaints” with the Ministry of Labor, the Ministry “generally contacts the business owner” for a resolution. Even this very weak right is not extended to workers in the “free trade zones” that benefit international businesses, nor to domestic, agricultural, or government workers within the UAE.

A foreign worker who is absent from work for more than seven days “without a valid reason” can be deported for up to a year by the government. Employers routinely restrict the movement of migrant workers by confiscating their passports. The State Department report cites cases of suicide and forced prostitution among migrant workers. There were also “widespread and frequent reports that foreign domestic workers were raped and sexually assaulted by their employers.”

The minimum monthly salary for domestic and agricultural workers was 400 dirhams (approximately $110) in 2010, while construction workers had a monthly minimum of 600 dirhams (approximately $164). Even at these pitiful levels, “foreign workers frequently did not receive their wages, sometimes for extended periods.” The State Department cites a case from August 2010 when “700 foreign workers outside Sharjah, abandoned by their employer, were without access to food or water” until local charities arrived. Such conditions prevail in a country where 80 percent of workers are non-citizens.

In addition to the millions of foreign workers, there are between 20,000 and 100,000 stateless persons (with no proof of any citizenship) in the UAE. The government granted citizenship to only 70 people in all of 2009, none of them from among the stateless. The UAE offers no protection to refugees—including those from countries where their lives or freedom are threatened—and is not a party to either the 1951 Convention or the 1967 Protocol on the Status of Refugees.

Concluded