American Letters 1927-1947: Jackson Pollock & Family, published March 18 by Polity Press, is a fascinating volume that sheds light in particular on the Depression years in the US and some of the intellectual and artistic trends that emerged during that harsh era.

LeRoy and Stella Pollock and their sons, 1918 © Charles Pollock Archives

LeRoy and Stella Pollock and their sons, 1918 © Charles Pollock Archives

Assembled by Francesca Pollock and Sylvia Winter Pollock, daughter and widow, respectively, of Charles Pollock, artist and elder brother of Abstract Expressionist painter Jackson Pollock, the collection was first published in France in 2009 as Lettres américaines: 1927-1947. (Francesca Pollock and Sylvia Winter Pollock reside in Paris.)

The co-editors explain, in their “Note of Intention,” that sharing the material with the public was a means of “taking a step back from the many ‘art critical’ interpretations” and keeping “the record straight.” They comment that the letters “counter the myth surrounding Jackson Pollock as an artist with a family of, at worst, ‘hicks’; at best, simple farm people, as if everything in that family happened by serendipity.”

Although it is quite possible the collection would never have seen the light of day but for the renown of Jackson Pollock, the latter’s evolution is hardly the central feature of the book. In fact, it is a subordinate element, and the letters come to an end on the eve of his great celebrity in the late 1940s.

The Pollocks’s drama is a fascinating one, although the portion of it that concerns the various family members’ encounter with radical politics in the 1930s and beyond hardly made them unique. This history is now suppressed as much as possible, but wide layers of the population in the US, certainly great numbers of thinking workers, intellectuals and artists turned sharply to the left under the conditions of the Depression.

As Michael Leja, of the University of Pennsylvania’s history of art department, notes in a useful introduction, “Even relative conservatives, such as the art critic Thomas Craven, were willing to concede that no artist of the 1930s should set out to celebrate America, because [in Craven’s words] ‘no self-respecting artist could glorify capitalism.’”

Jackson Pollock (born Paul Jackson Pollock, he dropped the first name and was generally known to family members as Jack) was the youngest of five brothers born to Stella and LeRoy Pollock between 1902 and 1912—four of them in Cody, Wyoming. Charles (1902-88), the oldest and an artist in his own right, was born in Denver.

In Jackson Pollock: An American Saga (1989), Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith observe that LeRoy Pollock long held left-wing views. “From his first encounter with socialist ideas…LeRoy responded to their call for fairness and equality.” He backed socialists such as Eugene V. Debs, the radical Industrial Workers of the World and, in 1917, “celebrated at the news that the workers of Russia had taken control of their government. Of his five sons, two would become active in the labor movement, and one would join the Communist Party. The other two would become artists.” In fact, this collection suggests two of the sons joined the CP (and that all of them, to one extent or another, partook of left-wing politics), but that is a secondary matter.

LeRoy and Stella (born in 1877 and 1875) led a peripatetic existence, which took them from rural Iowa to equally rural Wyoming, along with Arizona and various parts of California. They spent most of the years covered in this volume (LeRoy died in 1933, his wife a quarter-century later) in southern California. Leja explains that LeRoy “spent his life shuttling from job to job (as farmer, surveyor, plasterer, road construction worker, stonemason, dishwasher).”

Charles and Jackson Pollock in New York City, 1930 © Charles Pollock Archives

Charles and Jackson Pollock in New York City, 1930 © Charles Pollock Archives Three of the Pollock boys, Charles, Sanford (Sande) and Jackson relocated more or less permanently to the East Coast, or eventually the Midwest, in Charles’s case. Since the collection also contains letters from several of the sons’ wives (including, toward the end of the book, one from Jackson’s artist wife, Lee Krasner), the geographical and human permutations are considerable. And so is the range of subject matter.

The two decades of letters discuss, of course, family issues (money problems, marriages and births, the consequences of LeRoy’s death, various expeditions by family members around the country, Jack’s drinking, etc.), artistic questions (the varying influences of American populist and regionalist Thomas Hart Benton, the Mexican muralists, Pablo Picasso and others) and political matters (Roosevelt and the New Deal, the Communist Party and its role, strikes and social questions in the US, the Moscow Trials, the Spanish Civil War, the impending second imperialist war). A review can only touch upon the material raised in the book.

The reader will discover for him or herself intimate and colorful passages in the letters, including: LeRoy’s somewhat wistful remark in April 1929 that “Families grow up and scatter”; Charles, now relocated to New York City, lecturing his 17-year-old brother Jackson about the pitfalls of religion and “occult mysticism whose exponents in this country are commercial savants” [i.e., evangelist charlatans]; Elizabeth Feinberg, Charles’s first wife, introducing herself in 1931 to her mother-in-law by letter and thanking her for her “uncommonly generous spirit…a spirit that I have grown up to believe rather foreign from the ways of mothers”; Sande’s emphatic comment that he had attended a session of the CP-dominated Artists Congress in 1937, where artists George Biddle and Rockwell Kent “were the main speakers, and God how they stank”; and many more.

These were interesting people. Both parents were obviously remarkable. In one of the earliest letters, from September 1928, LeRoy, off on a job presumably, writes to his 16-year-old “Son Jack,” “The secret of success is concentrating interest in life, interest in sports and good times, interest in your studies, interest in your fellow students, interest in the small things of nature, insects, birds, flowers, leaves, etc. In other words to be fully awake to everything about you & the more you learn the more you can appreciate, & get a full measure of joy & happiness out of life.”

Without question, the Wall Street crash a year later and ensuing devastating slump were defining events in the lives of the younger Pollocks, as they were for millions and millions of others. Whatever predisposition they might have had to a critical attitude toward the existing social order was qualitatively deepened by the hardships inflicted on the working population by the disaster of the Depression.

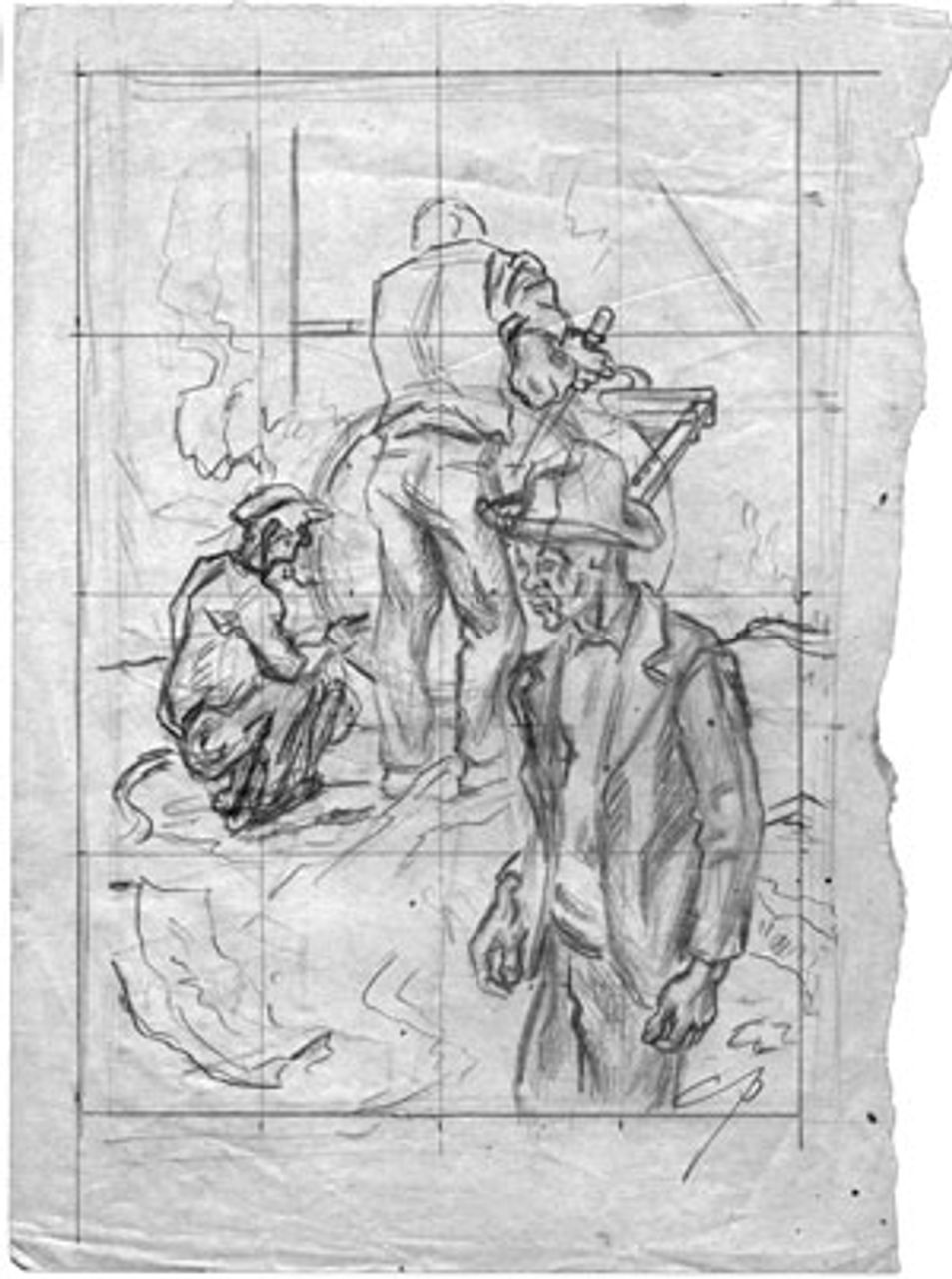

Three Workers (Charles Pollock), 1930 © Charles

Three Workers (Charles Pollock), 1930 © CharlesPollock Archives

As early as 1931, Jackson, 19, recounts a trip across the US during which he “met a lot of interesting bums—cutthroats and the average American looking for work—The freights are full, men going west, men going east and as many going north and south—millions of them.” A year later, he writes to his mother from New York, “Conditions here are unbelievable, families without clothing, food and housing.”

A fourth brother, Frank describes a drive through western Pennsylvania in 1931, when, needing water for his car’s radiator, he stopped at what appeared to be an abandoned farm. “There was not a sign of life.” He called through the door “and out of the darkness came a squeaky voice followed by a withered little woman who stumbled in hesitancy, and then kept saying over and over again as though talking to herself, ‘Yes, I guess, I guess you can have some water.’”

Trips by various brothers to the Deep South and Texas produce similar accounts, of “incredible poverty” and a life for local people that “is indescribably barren and harsh.” A daughter-in-law, new to New York City, notes in 1936 “the material evidence of extreme wealth and miserable poverty.”

The five brothers, their wives and their mother struggled themselves with the conditions of life. Charles, Jackson and Sande attempted to pursue careers as artists. The latter two qualified for the Federal Art Project, set up in 1935 as the visual arts division of the Works Progress Administration (a public works program of Roosevelt’s New Deal administration), which provided a small stipend to artists and commissioned them to paint murals in public buildings, teach art and even make paintings and sculptures. Demeaningly, the artists were required to prove they were destitute and, furthermore, swear they had never been affiliated with the Communist Party.

Steel Mill, Gary, Indiana (Charles Pollock), 1933 © Charles Pollock Archives

Steel Mill, Gary, Indiana (Charles Pollock), 1933 © Charles Pollock ArchivesUnder the Project’s rules, artists were not permitted to pool their resources, a regulation that Sande and Jackson regularly flouted. The fear of having their living arrangements found out caused them considerable anxiety, as did the recurring anti-Communist investigations. In a typical comment, Sande observes in 1940, “They [Project officials] are dropping people like flies on the pretense that they are Reds, for having signed a petition about a year ago to have the CP put on the ballot.”

All the Pollock brothers turned to the left in the 1930s. The fifth brother, Marvin (or Mart) joined the Communist Party and remained a loyal Stalinist during much of the period covered by these letters. Charles writes to his brother Frank in 1938, “Since the Party laid down the line, Mart won’t even write, for fear, I suppose, of being contaminated.” In 1937, Sande notes to his mother that “We were glad to hear that Frank is in the Party.”

Charles Pollock never joined the CP, instead supporting for a time the Communist Party (Opposition), headed by Jay Lovestone, the American extension of the Right Opposition, which originated in the expulsion of Nikolai Bukharin and his supporters from the Soviet leadership and Communist International in 1929. The Lovestone group, which existed from 1929 to 1940, functioned under various names, before dissolving itself on the eve of the Second World War. Lovestone went on to become the chief strategist of the AFL-CIO’s counterrevolutionary activities abroad in the postwar period.

Jackson Pollock, although not prone to accept the discipline of a political organization, along with Sande, worked on various events sponsored by the Communist Party, through a workshop taught by Mexican artist and later would-be assassin of Trotsky, David Siqueiros: including a float for the 1936 May Day parade and “art propaganda” for a party convention at Madison Square Garden in New York the same year.

It should certainly be noted that the drama of Jackson Pollock’s early life and evolution, including the story of his emotional ups and downs, forms an important undercurrent running throughout the last decade of the letters collected here. The artist, who suffered from bouts of mental instability and alcoholism already by the mid-1930s, found the world especially challenging.

From New York, Sande communicates in 1939 to Charles—by now in Detroit (where he had worked for the United Auto Workers for a year)—somewhat laconically (he was far less laconic on other occasions), that “Jack is still struggling with problems of painting and living.” The latter’s remarkable talents were recognized by other family members, even when they admitted they had difficulty understanding his work.

Two years later, Sande genuinely unburdens himself to Charles about the serious problem he and his wife have faced “these past five years. The subject is Jack,” explaining (to a certain extent, complaining) that caring for his younger brother “has taken much of our energy.” He reveals that Jackson had been hospitalized in 1939 for six months in “a psychiatric institution…. He is afflicted with a definite neurosis.”

In the same letter, Sande notes that Jackson was “doing work which is creative in the most genuine sense of the word.… His thinking is, I think, related to that of men like [German painter Max] Beckmann, [Mexican muralist José Clemente] Orozco and Picasso. We are sure that if he is able to hold himself together, his work will become of real significance. His painting is abstract, intense, evocative in quality.”

In any event, at one time or another, most of the Pollocks expressed intense hostility toward American capitalism and the desire to see its demise. In February 1933, for example, Jack (in New York City) writes his father, only a month before the latter’s untimely death, “for heck sake don’t worry about money—no one has it. This system is on the rocks so no need to try to pay rent and all the rest of the hokum that goes with the price system.”

Eight months later, well into the first year of Roosevelt’s New Deal administration, Frank tells his brother Charles in a letter from California that “our chances of changing the system by means of the vote are slight…nothing short of an armed revolution will attain the desired ends” and decries the miserable results of the social-democratic reformists in Europe.

In August 1936, on the eve of Roosevelt’s second election victory, Sande (in New York) writes to his mother on the West Coast that the victory of Republican presidential candidate Alf Landon “might not be so bad either, for then we could start the shooting.”

And the Pollock matriarch herself obviously bore no love for the system, writing to two of her sons and a daughter-in-law in New York in 1934, with obvious approval, that “Marvin says to tell you that he is getting more revolutionary every day….”

The antipathy felt by the Pollock family, and many others, for the American social order, responsible for so much suffering, was no doubt deep-rooted and sincere. The reader derives from the letters a highly sympathetic overall picture of the family, which produced at least one artistic genius. However, a serious approach also involves examining the social influences and the limitations of the views put forward. It would be misleading and patronizing to cover over the serious historical weaknesses of American radicalism, whose conceptions find various reflections in this volume of letters.

The “Popular Front” politics of the Communist Party, which meant the continued subordination of the working class to bourgeois politics through support for Roosevelt and the Democratic Party, had a considerable following within certain social layers in the US, even among some of those appalled by the opportunist twists and turns of Stalinist tactics and the bureaucracy’s enormous crimes in the USSR and elsewhere.

Stalinism was not simply an import from Moscow, although the funding supplied by the Kremlin helped solidify its hold. Its shallow, nationalist, populist-flavored policies also had roots in various American political currents and realities. Relative indifference to questions of principle, especially those not involving directly “American experience,” was encouraged by CP leaders, but was not invented by them.

The comments recorded in American Letters 1927-1947 treating social conditions, the upsurge in the class struggle (the San Francisco general strike of 1934 and other events), the New Deal, etc., are often pungent, generally honest and well-intended, but they also bear witness to retrograde political and social influences working on the Pollocks.

In their attitudes toward Franklin D. Roosevelt, for example, the brothers reveal something about the provincial, pragmatic nature of American radicalism in general and, specifically perhaps, the residue of agrarian populism with which their parents must have been familiar. The Pollocks were far from uncritical of the Democratic administration. However, in the end, they always managed to end up supporting Roosevelt’s re-election, even while favoring in principle the building of a labor party.

This is Sande in 1936: “Without having any illusions about the man [Roosevelt] we hope nevertheless he is re-elected. And by nineteen forty the Farmer Labor Party will have come to maturity and will be strong and beautiful.” He tells Charles in another letter later that same year, “It seems reasonable to believe that after the elections, Roosevelt is certain to retrench in favor of the reactionaries.” Following the 1936 election, Charles writes his mother, “It has been a great victory for Roosevelt and his policies and surely signals a significant point in our history.”

The Pollocks, as far as the letters reveal, felt little sympathy for the Trotskyists, who were dedicated to the political independence of the working class from the Democrats, and, of course, the exposure of the crimes and betrayals of the Stalinist bureaucracy and the Communist International.

In the most explicit and revealing statement, Charles Pollock writes Frank in February 1937 (in reply to a comment by the latter expressing confusion about the infamous show trials of the old Bolshevik leaders being staged in Moscow), “I am not at all convinced that the trial was above board, but then I am not so much concerned with the legalities, or lack of them, as I am with certain other implications. Trotsky was long ago discredited. I do not think all evil should be laid at his door but insofar as the conspirators [i.e., Stalin’s frame-up victims] were Trotskyite the logic of their position would necessarily lead them to sabotage [and] terroristic methods. But in an undemocratic party there is no room for constructive criticism and there is, I think, great danger that all criticism of whatever sort will be labeled Trotskyite. Indeed, this is already happening in Spain and elsewhere.”

The comment hardly does Pollock credit [why was he not concerned about the Moscow Trials’ monstrous lack of “legalities,” part of Stalin’s genocide against socialist workers and intellectuals in the USSR?], although it probably reflected the average consciousness of the left-liberal intellectual in the US. This sort of attitude, with its lack of concern for the great issues at stake, had terrible consequences for the American left and American political life in general.

The other brothers weigh in on the Moscow Trials. Sande wonders to Charles “what in hell” the trials are all about and Frank, also in a letter to Charles, asks, “Who are we to trust?”

Whatever individual attitudes the brothers adopted toward Stalin’s show trials and related events in Spain and elsewhere, the volume under consideration further demonstrates that the experiences of the period 1936-40 engendered among the artists and intellectuals a great disappointment and disillusionment, which overshadowed artistic production in the second half of the last century and into the first decade of the present one.

That a regime claiming to represent socialism, the noblest cause ever undertaken by humanity, was guilty of horrendous crimes and falsifications did untold damage to the confidence of the artists in the possibility of changing the world for the better. The Communist Parties would continue to exist and even enjoy popular support for decades, but the stench of Stalin’s crimes could never be removed.

Succinctly, disturbingly, summing up the conclusions that many intellectuals would draw, Sande writes to Charles in 1938, “The Russian trials have knocked the guts out of my beliefs toward any kind of Communism or proletarian…dictatorship. I know damn well that I am wrong but I am developing a shell of extreme fatalism. The human race seem to me a pack of dogs and were it possible I would have no truck with them.”

In 1939, he returns to the theme, in a letter to the same brother: “The whole international progressive movement seems to be without leadership or direction—is paralytic and ineffective. I agree with you there is no revolutionary movement in the real sense of the word…. I find myself thinking in terms of nihilism.” In a letter to family members in 1940, Sande comments, “Have no idea where you stand politically but I should guess the same place we do – confused.”

It is in this context, and not merely a personal one, that one might read Jackson Pollock’s well-known comment in the summer of 1940, in a letter to Charles in Michigan: “I haven’t much to say about my work and things – only that I have been going through violent changes the past couple of years. God knows what will come out of it all – it’s pretty negative stuff so far.”

The heroic, doomed project of postwar Abstract Expressionism (and his own early death in an automobile crash in August 1956) still lay ahead. The question inevitably poses itself: to what extent did the social disappointment and disillusionment (confusion, nihilism, pessimism) of the late 1930s shape the development of the New York School artists, including Pollock, and the degree to which psychoanalysis and “the inner world” ultimately came to dominate their work?

American Letters 1927-1947 sheds light on genuinely important matters, and should be of interest to anyone concerned with the historical roots of our cultural and political circumstances.

The author recommends:

The limitations of Ed Harris's Pollock

[31 March 2001]