In a carefully stage-managed performance aimed at legitimizing military rule, the newly appointed Egyptian prime minister, Essam Sharaf, visited protesters in Cairo’s Tahrir Square Friday and professed his sympathy for the struggle that ousted President Hosni Mubarak.

Sharaf, a cabinet minister under Mubarak from 2004 to 2006, was named prime minister the previous day by the Armed Forces Supreme Council, which has ruled Egypt since Mubarak resigned the presidency February 11. The military leadership evidently concluded that Ahmed Shafiq, Mubarak’s last prime minister and a former air force general, was too closely identified with the old regime and had to be replaced by a figure less politically discredited.

The first test of the new prime minister was to visit Tahrir Square, where a planned protest demanding the resignation of Shafiq was turned into a celebration of his ouster. Sharaf paid tribute to “the martyrs of the revolution, the thousands who were injured and the families of the victims,” while at the same time ignoring calls from the crowd for the dissolution of the state security forces responsible for the deaths and injuries.

Egyptian youth protesting in Tahrir Square

Egyptian youth protesting in Tahrir SquareProtesters chanted, “The people want the end of the State Security,” the branch of the Interior Ministry charged with suppressing political opposition. Sharaf merely remarked, pointedly using the future tense, “I pray that Egypt will be a free country and that its security apparatus will serve the citizens.”

After he declared, “I am here to draw my legitimacy from you. You are the ones to whom legitimacy belongs,” Sharaf was hailed by some of the demonstrators, who carried him on their shoulders. But he also urged “patience” with the new regime, which except for the absence of Mubarak at the top is virtually identical to the old regime.

Many protesters expressed skepticism about Sharaf, chanting for him to take his oath of office as prime minister in Tahrir Square, in front of the Egyptian people, rather than pledging allegiance to Mubarak’s generals. Sharaf demurred and eventually left the square.

Two youth carry a message that reads, “We demand

Two youth carry a message that reads, “We demandthe abolition of the state security apparatus”

Two youth who spoke to the World Socialist Web Site said they came to Tahrir Square because they still have many demands. One said, “There are achievements, we brought Mubarak and Shafiq down, and we are proud of it, but this revolution is not finished. We demand the end of the military rule since 1952. The military should go back to the barracks and the state security apparatus must be abolished. We want true democracy.”

Both said they also wanted to show solidarity with protesters in Libya, Yemen, Bahrain and other countries, just as they had been inspired by Tunisia.

The young man with the Egyptian flag has been camping in Tahrir Square since the protests began January 25

The young man with the Egyptian flag has been camping in Tahrir Square since the protests began January 25Another young man had been camping out at Tahrir Square since the beginning of the revolution. “Nothing has really changed yet,” he said. “The old regime is still in power. I don’t leave before all our demands are met and the whole system is brought down. There must be justice for the more than 350 martyrs killed by the regime.”

One of the first actions of Sharaf’s government was to announce that a nationwide referendum would be held March 19 to ratify eight amendments to the Egyptian constitution proposed by a council of academic and legal experts appointed by the military.

The purpose of this maneuver to gain the semblance of popular support for the military regime through a vote rubber-stamping relatively minor changes in the existing reactionary constitution. Most of the amendments would merely open up the presidential election to opposition candidates and limit any president to two four-year terms.

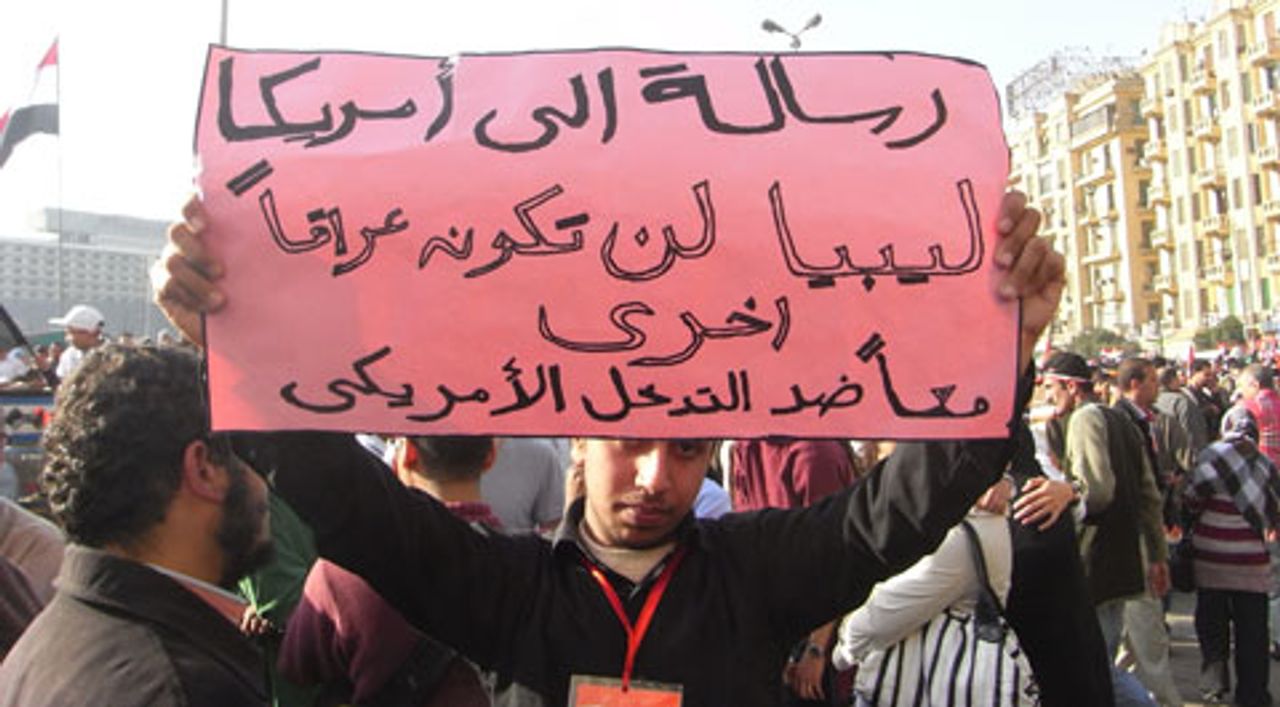

The poster reads: “Letter to America: Libya will not be another Iraq. Together against an American intervention”

The poster reads: “Letter to America: Libya will not be another Iraq. Together against an American intervention”The amendments would maintain the power of the government to declare emergency rule, the legal basis for the banning of virtually any form of political opposition for the last three decades, as well as the suppression of strikes and other protest actions by the Egyptian working class.

The largely friendly reception for Sharaf in Tahrir Square was prepared by the active collaboration of both older and younger layers of the bourgeois liberals who came to prominence during the three weeks of demonstrations that swept away Mubarak.

Mohamed ElBaradei, the former United Nations official and Nobel Peace Prize winner, hailed the replacement of Shafiq by Sharaf, declaring, “Today, [the] old regime has finally fallen. We are on the right track.”

ElBaradei’s organization, the National Association for Change, issued a statement of support for the military regime. "The decision of the Supreme Council is a considerable response to peoples’ demands,” the group said. “We hope the new government achieves our aspirations and we hope the Supreme Council meets the rest of demands, including the formation of a presidential council to run the country during the transitional period, the abolition of emergency law, and release of the rest of the political detainees.”

Former presidential candidate Ayman Nour, leader of the liberal Ghad party, praised the appointment and declared Sharaf to be “on the right track,” adding, “But we wished he had spoken about his agenda and his plans about emergency law and the state security establishment.”

ElBaradei and Amr Moussa, secretary-general of the Arab League, met March 2 with military leaders to discuss possible replacements for Shafiq in a transitional government.

ElBaradei is the opposition figure most publicized in the Western media, but there is little popular support in Egypt for his conservative politics. He has proposed postponing new elections for at least a year while the country is ruled by a three-man interim council, consisting of one military officer and two civilians (one of them presumably himself).

The Muslim Brotherhood, the largest opposition group under the Mubarak dictatorship, also backed Sharaf’s selection. In response, the military regime released two prominent members of the group’s leadership from prison. Khayrat Al-Shater and Hassan Malik were tried by a military tribunal in December 2006 and sentenced to seven years in prison.

Sharaf was one of several names proposed as replacements for Shafiq during a meeting between the military council and leaders of Coalition of the January 25th Revolution Youth, which called many of the protests in Tahrir Square. One of this group, Nasser Abdel Hamid, told Reuters news agency that the coalition would pull back from further protests. “We have to let them breathe so they can work,” he said, referring to the new cabinet headed by Sharaf.

As transportation minister in 2004-2006, the engineering professor had a reputation for comparative independence, eventually quitting his position over the cover-up of a major railway accident. But he remained a prominent member of Mubarak’s political front organization, the National Democratic Party, serving on its policies committee.

Sharaf was one of the former Mubarak officials who saw which way the wind was blowing in time to publicly embrace the protest movement, turning up briefly in Tahrir Square with other professors from Cairo University the week that Mubarak resigned.

According to reports in the Egyptian press, Sharaf met Thursday night with 15 members of the coalition of youth groups, only hours after his appointment. Amr Salah, one of the 15, told Al-Masri Al-Youm that Sharaf spent most of the 15-minute meeting listening to their demands, which included the dissolution of the state security apparatus and the release of political prisoners. They in turn offered their collaboration to the new prime minister.

Another leader of the coalition, Abdel Hamid, told the Egyptian press that the group was forming “awareness committees” to convince protesters to clear Tahrir Square by Saturday, March 5.

Another coalition leader, Abdelrahman Samir, said, “We want to be flexible and to show that we respond when our demands are met … our role is not only to protest, we also have to build our country.” Samir revealed that the coalition had promised Armed Forces Chief of Staff Sami Anan, the number two figure in the military hierarchy, that protests would stop if Sharaf replaced Shafiq.

Meanwhile, there are new reports of violence and brutality by the military regime. A young man who was arrested by military police February 26 during their attack on demonstrators in Tahrir Square was sentenced by the Supreme Military Court to five years in prison this week. Amr Abdallah al-Beheiry was brutally beaten, then charged with assaulting a public official and breaking curfew.

Ever since the February 26 attack, young people have been filtering back into Tahrir Square, setting up tents and preparing for another occupation protest centering on demands for the ouster of Shafiq, the dismantling of the security forces and the release of political prisoners.

The sacking of Shafiq and his replacement by Sharaf is only the latest of a series of gestures by the military regime to provide the semblance of change and reform, while blocking any real challenge to the property and privileges of the Egyptian capitalist elite, of which the top military officers are a prominent part.

These token actions have included the firing and detention of particularly hated officials of the Mubarak regime and the freezing of the assets of the Mubarak family and their closest cronies—except, of course, those cronies who comprise the Armed Forces Supreme Council itself. All these officers, including their chief, Defense Minister Mohammed Tantawi, are long-time allies of the former president.