Gil Scott-Heron, the African-American poet and musician known for his scathing and beat-driven social protest songs, died May 27 at St. Luke’s Hospital in New York City, at the age of 62. While not a great artist, Scott-Heron displayed considerable talent as both a writer and a musician.

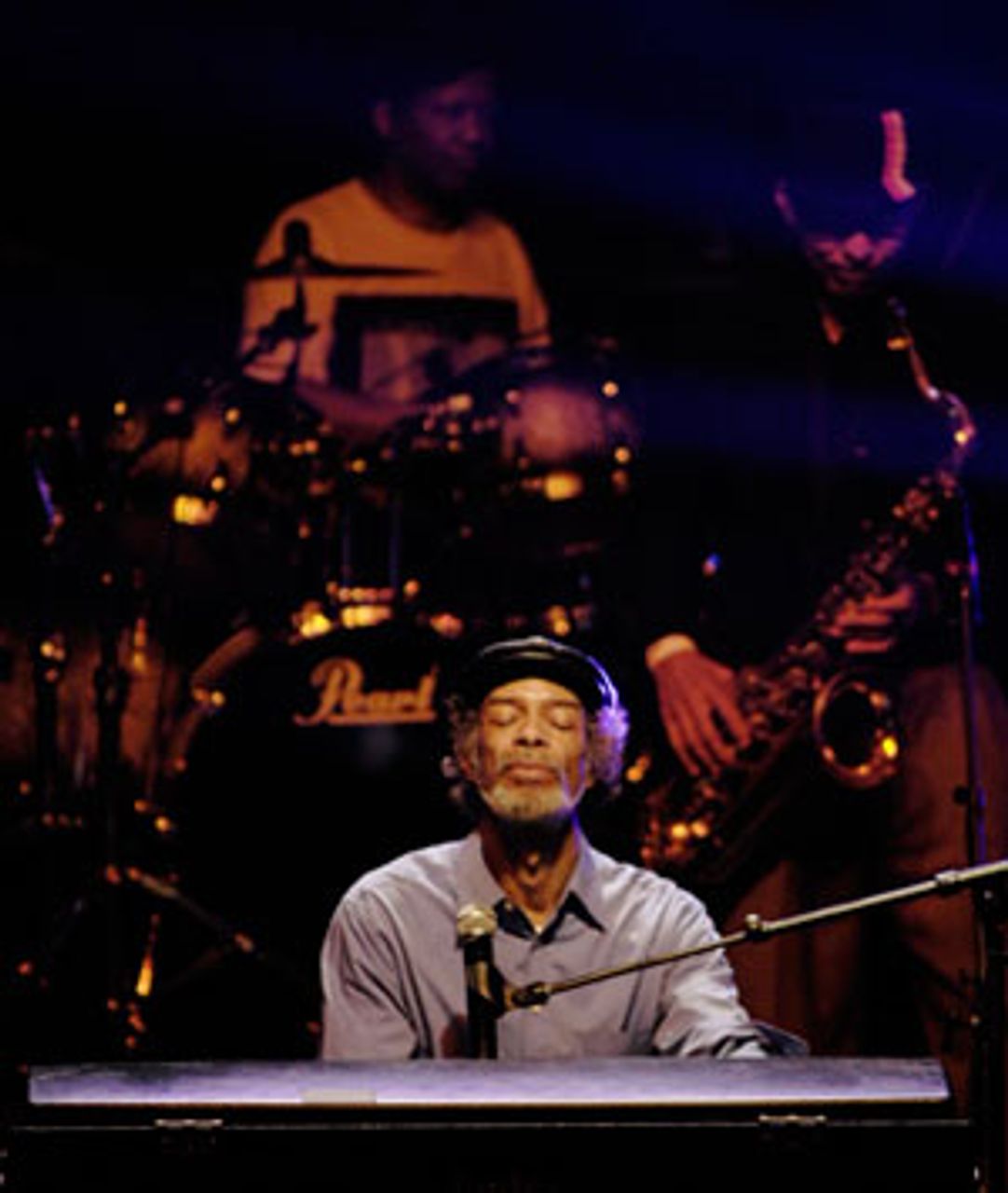

Scott-Heron performing at the Regency Ballroom

Scott-Heron performing at the Regency Ballroom

in San Francisco, 2009

His most interesting work revealed a deep feeling for the most oppressed layers of society and an ability to communicate with sensitivity and musicality something of their day-to-day struggles. His efforts were ultimately limited, however, by the politics and culture of black nationalism, of which Scott-Heron was a lifelong advocate. There is a great deal in his music and thinking that one simply can’t go along with.

Gil Scott-Heron was born April 1, 1949 in Chicago. After his parents separated when he was very young, Scott-Heron moved to his grandmother’s home in the South. Raised by his mother and grandmother, the future singer and poet grew up in poverty in Jackson, Tennessee. His teenage and young adult years coincided with the eruption of the civil rights movement and these events had a great effect on the future poet.

In a 2009 interview, Scott-Heron recounted the influence his grandmother and the civil rights struggle had on his early world-view: “As someone living in Tennessee in the late ’50s and early ’60s,” he said, “you were aware of the fact that there were some people trying to do something … [my grandmother] was concerned about the organization of the NAACP, the integrating of the school system, the changes in the economic circumstance.”

A talented writer from an early age, Scott-Heron won a literary scholarship to attend the highly selective Ethical Culture Fieldston School in the Bronx, New York. He later enrolled at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, the historically black university where his favorite writer, poet Langston Hughes, had been a student. Here Scott-Heron met keyboardist Brian Jackson, the musician with whom his own musical career would be closely associated.

Scott-Heron published two novels by the time he was 21 and was further inspired to pursue poetry and music after attending a performance by The Last Poets, a radical group of poets and musicians whose work bore the heavy influence of black nationalism.

Gil Scott-Heron circa 1995 [Photo credit: www.daveblumenkrantz.com]

Gil Scott-Heron circa 1995 [Photo credit: www.daveblumenkrantz.com]

The nationalist perspective, with which Scott-Heron had also by this time aligned himself, drew in a significant section of African-American youth during the 1960s and 1970s. Appalled and outraged by official Jim Crow racism in the South and de facto segregation and discrimination in the North, but either cut off from or opposed to a socialist critique, the black nationalist forces rejected the revolutionary role of the working class and the need to unite workers across racial and national divides in a common struggle.

In his most interesting work, Scott-Heron demonstrated a sensitivity to the most oppressed in society, particularly poor and working class African-Americans, but his limited perspective left him ultimately unable to grasp the complexities of social relations and reflect them artistically. For Scott-Heron, race not class was the fundamental social divide. Such a false view cramps and distorts one’s view of humanity, making it difficult to treat life in a sufficiently broad and integral fashion.

Scott-Heron’s musical career got its start in 1970, when he released his debut album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox [a famous corner in New York City’s Harlem]. It was on this album that his most famous song, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” first appeared, although a more popular recording of the song would be released on his follow-up album, Pieces of a Man, in 1971.

While it continues to be popular and has become something of a radical anthem, the song is not perhaps the most serious piece in Scott-Heron’s body of work. Nonetheless, it sticks in the memory for its wonderful, sarcastic attack on official American life, including among its targets President Richard Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew. Scott-Heron, emulating the cadence of a commercial spokesman, chants anti-slogans such as “The Revolution will not be brought to you by Xerox in four parts without commercial interruptions!”

Of course, it becomes clear by the end of the song that “revolution,” for Scott-Heron, was synonymous with “black liberation” and white workers had no place in it. “The Revolution will not be right back after a message about a white tornado, white lightning, or white people,” he sings.

The 1971 recording features a memorable bass guitar riff played by the great jazz musician Ron Carter, which combined with Scott-Heron’s angry, urgent delivery, and a somewhat exhilarating refrain, accounts for much of the song’s appeal. It is exciting, musically. [Listen to it here.]

Scott-Heron would be enormously productive between 1970 and 1982, producing 13 albums during that time, including Pieces of a Man (1971), Winter in America (1974), The First Minute of a New Day (1975) and From South Africa to South Carolina (1976).

What does one find when listening to these albums today? The musicianship of Scott-Heron, Brian Jackson and the bands they assembled was generally excellent. Scott-Heron possessed an expressive voice and his spoken word pieces feature a captivating rhythm. Often his poems come across more powerfully when heard than when read on the page. Though his voice was not classically trained, when singing, Scott-Heron could convey sorrow and heartache with a stirring resonance.

It is not difficult, after just a small sampling of his music, to see why the work of this charismatic performer and lyricist had such an impact on later generations, particularly among more thoughtful hip hop artists such as Public Enemy and Mos Def. (Though he consistently rejected the title, Scott-Heron was often considered to be one of the “godfathers of rap music.”)

One must say, however, that in surveying Scott-Heron’s career, one tends to find certain admirable songs, but rarely ever fully satisfying albums. Often very moving and effective songs with narratives about the struggles of working people are immediately followed by more “radical” material in which ultimately reactionary political aims are defended. Sharp commentaries on marketing idiocy, social complacency and corrupt politicians are followed by repeated assurances that self-determination, “black liberation” or “black capitalism” provide a way out of it all.

At his best, Scott-Heron could speak and sing powerfully about the effects of poverty and economic hardship on the lives of working class families in songs such as “Pieces of a Man,” in which one finds the following devastating passage:

I saw my daddy greet the mailman

And I heard the mailman say

‘Now don’t you take this letter to heart now Jimmy

Cause they’ve laid off nine others today’

He didn’t know what he was saying

He could hardly understand

That he was only talking to

Pieces of a man

In songs like “Three Miles Down” he could sing movingly about exploited mine workers, or about the trauma and tragedy of substance abuse in “The Bottle,” “Home is Where the Hatred Is,” and “Angel Dust.”

The haunting “Did You Hear What They Said,” from the 1972 album Free Will, about a young man killed in the Vietnam War, makes a strong impression. But, regrettably, on the same album one finds “Ain’t No New Thing,” a song in which Scott-Heron stupidly accuses Elvis Presley, Benny Goodman, Janis Joplin and others of “cultural rape” because they performed “black music.”

In 1978 Scott-Heron recorded the moving “Angola, Louisiana,” about Gary Tyler, an African-American youth falsely imprisoned in 1974 for a crime he did not commit in a politically and racially motivated frame-up. Tyler remains in prison to this day. (See “Renewed calls for the freedom of Gary Tyler” and listen to Scott-Heron’s song here.)

As time went on, and the wave of radical protest and militancy of the 1960s and 1970s, which had lifted Scott-Heron up and inspired him, began to subside, one felt more and more in his music a brooding pessimism and a suspicion that all was lost. The singer was unprepared for the changes taking place in social life and unable to make sense of them. A political demoralization took hold.

By the 1980s, a decade that produced numerous significant defeats for the American and international working class, Gil Scott-Heron began to disappear artistically. He only produced two more albums over the next 30 years. He began, ironically and tragically given his songwriting history, to struggle seriously with substance abuse, particularly crack cocaine. He spent much of the last decade in and out of jail for drug possession. He was constantly in poor health. His fate was in many ways a tragic one.

At the time of his death, Scott-Heron was trying to turn things around. His final album, I’m New Here, was released in February 2010. It was his first new album in 16 years.