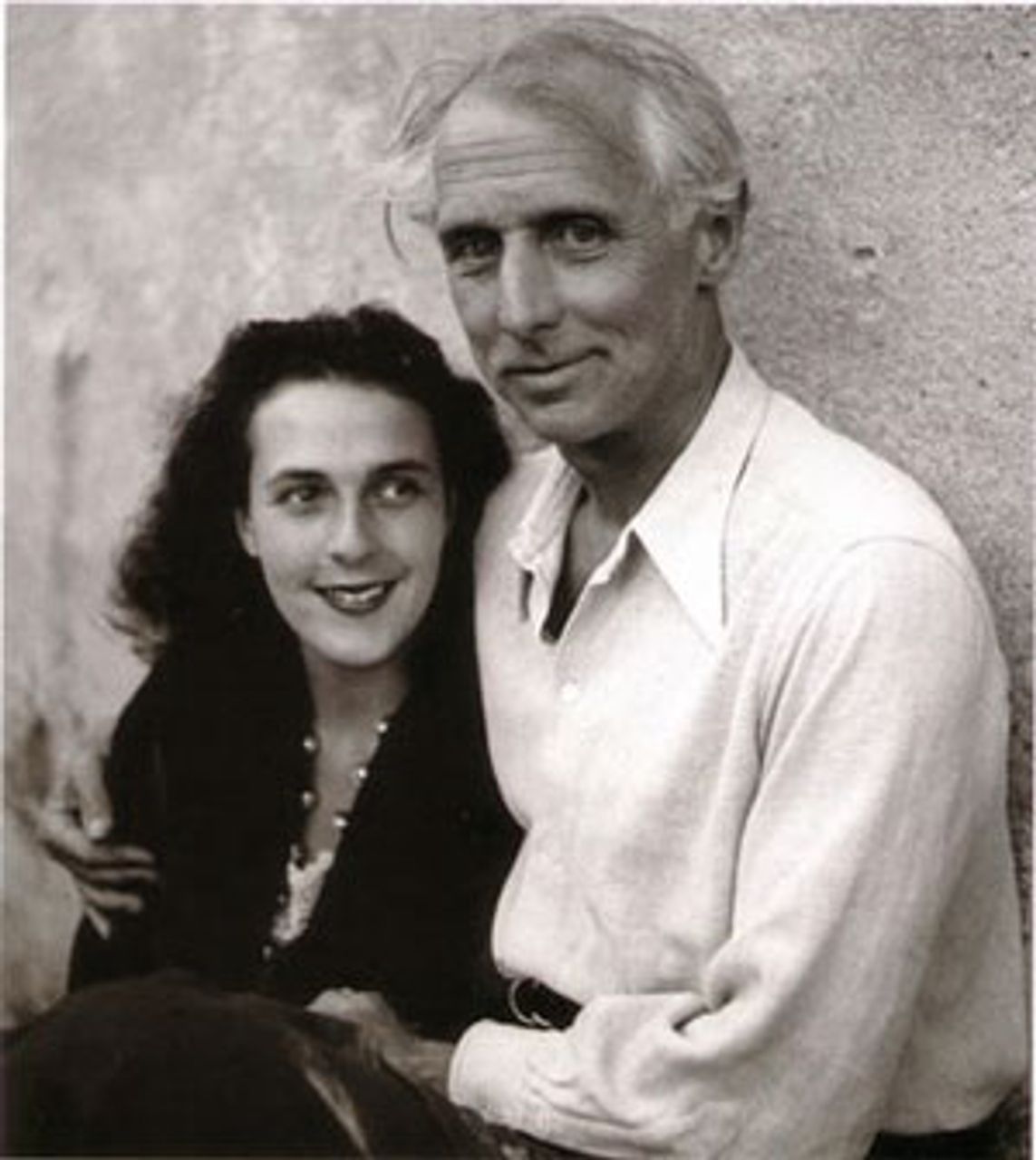

Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst in 1937

Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst in 1937Leonora Carrington, who died May 25 at the age of 94, was one of the last surviving participants in the Surrealist movement of the 1930s.

She remained active as a painter and sculptor throughout her life, and continued to inspire younger generations. Two weeks after her death an international group of Surrealists met in Athens to explore her proposal for “Surrealist survival kits”.

Her best work teems with passion and ferocious self-investigation in her rebellion against the privilege of her upbringing. At times she seems an unreliable witness to the facts of her own life, but chiefly because she is such a reliable witness to its emotional content.

Carrington was born into a wealthy textile manufacturing family in Lancashire. Her father’s family had patented a new loom attachment that led to the development of new woollen fabrics. She would later compare her father to a Mafioso. Her Irish mother invented fabulous and unlikely family connections across Europe.

Both parents read Carrington their preferred fantastic literature. From her mother she heard the work of James Stephens, who based much of his work on Irish traditional stories, while her father preferred the Gothic tales of W.W. Jacobs. Carrington also heard ghost stories from her Irish nanny, Mary Kavanagh. All of these would feed the development of her distinctive style, where animals and fantastical creatures merge with alchemical imagery.

In later life Carrington would downplay the family’s wealth, perhaps because of her rejection of its privileges. But her upbringing was that of an affluent provincial lady. Initially educated at home by governesses, she was sent to a convent school at the age of nine. This was the start of a series of unhappy experiences with boarding schools. She was alienated by both the Catholic regulations she encountered at the convent schools, and by the expectations of the British upper class.

She was expelled from school more than once. Nuns at one school were uneasy at her ambidextrousness and her habit of mirror-writing. She would later paint with both hands. Her father was hostile to her developing interest in art, which he thought “horrible and idiotic”. Carrington said his thinking was that “you didn’t do art—if you did, you were either poor or homosexual, which were more or less the same sort of crime”.

Her mother encouraged her interest, and Carrington was sent to a finishing school in Florence, Mrs. Penrose’s Academy of Art. Here she encountered the Sienese masters whose colours influenced her painting. She returned full of enthusiasm, but her father pushed her back into the social “Season” of the bourgeoisie. A “coming-out” ball (the first flotation of available young debutantes on the social and marriage market) was held for her, and she was introduced to aristocratic society.

Her attitude to this can be gauged from one of her most remarkable stories, The Debutante, in which a young society woman does a deal with a hyena to take her place at a ball. The hyena wears a face it has chewed off a maid. Recognised at the ball by its smell, the hyena eats the face before leaving in disgust.

Carrington was unswayed by the allure of the Season, and insisted on studying art further. After Chelsea College of Art, she enrolled in the private academy of the Cubist Amédée Ozenfant. This was in 1936. She visited the International Surrealist Exhibition held in London that June, the first exposure of Surrealism in Britain. Her mother also gave her the book on Surrealism edited by Herbert Read (later knighted for his services to literature), which had Max Ernst’s Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale on the cover.

Her accounts of these events are chronologically confusing, because they convey the significance of the moment to her. She later recalled seeing the Ernst image as “like a burning inside; you know how when something really touches you, it feels like burning”.

She was already exploring a fantasy world in her drawing, rather different from the work of her fellow students at Ozenfant’s academy, and she found in Surrealism a means of expressing that.

In 1937 she met Ernst at a dinner-party. He was 46 and married. Carrington left for Paris to join him. The situation was complicated, as Ernst was also still spending time with his wife, Marie-Berthe. On one occasion Carrington struck her during an encounter in a café. Carrington and Ernst subsequently moved to Provence.

This marked Carrington’s first flourishing as a Surrealist. The Inn of the Dawn Horse (Self Portrait (ca. 1936-37) incorporates much of the imagery found in The Debutante.

Stories like Little Francis explore her reactions to the Catholic schools she had endured as a child.

She participated in the Surrealist group in Paris, exhibiting with them for the first time in 1937. She met and got to know many of the artists in and around the group, including Luis Buñuel, Benjamin Péret, and Man Ray. Salvador Dali called her “a most important woman artist”.

Carrington had little time for attempts to treat her as a subordinate. “I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse”, she said later, “I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.”

She found, with Ernst and the circle around the Surrealists, a fertile collaborative environment, which she later called “an era of paradise”. She wrote and painted, and found creative outlets for her high spirits and practical jokes.

The impending war saw Carrington, with other Surrealists, join the Kunstler Bund, an organisation to assist Jews and threatened artists escape from occupied Europe. After the French declared war on Germany in 1939, Ernst was interned as an enemy alien. Carrington supplied him with paints, and lobbied for his release, but the situation was increasingly dangerous. Ernst’s work had also been targeted as “degenerate” by the Nazis.

Carrington and others secured his release. The following year, as the Nazis advanced, Ernst was arrested again, this time by the Nazis. He was interned further away, along with fellow Surrealist Hans Bellmer.

Carrington again sought Ernst’s release, but got no joy in Paris. Returning to Provence, she suffered a mental breakdown that she recounted in the extraordinary Down Below. This reads differently to her other work. It had to be written and reconstructed several times, and eventually only saw completion through the encouragement of the surgeon and Surrealist Pierre Mabille. It is a powerful account of her traumatic experiences.

Carrington went to Spain in search of a visa for Ernst, but was incarcerated in a mental institution and forcibly treated with Cardiazol, a spasm-inducing hallucinogen. The versions of Down Below differ textually, but all suggest some degree of physical and sexual abuse. Carrington later described her breakdown as “very much like having been dead”.

Her father sent a business contact to get her out of the hospital and send her to South Africa, with the intention of placing her in a sanatorium. She escaped from her minder in Lisbon. Recalling the Mexican diplomat Renato Leduc, who had been a friend in Paris, she fled to the Mexican embassy.

Leduc, whom she described as “neglectful but nice”, married her in order to take her to New York with him. While they were waiting for a ship, Ernst arrived in Lisbon having escaped his internment. With him were his ex-wife, various children, the art collector Peggy Guggenheim (who would later marry Ernst), and her ex-husband.

Carrington spoke highly of Guggenheim’s generosity. Although pained by Ernst’s continuing attachment to Carrington, Guggenheim offered to pay her air passage to New York. Carrington declined, and she and Leduc sailed instead.

There was a movement of numerous radical artists to New York at this time, many funded by Guggenheim. Others moved on elsewhere. Carrington stayed only a few months, dissolving her marriage to Leduc, before moving to Mexico, where she remained for most of her life. She left for a year in 1968 in protest at the massacre of demonstrating students. In 1985 she moved to New York for a period after two earthquakes devastated Mexico City.

Mexico prompted a drive to paint. Carrington explained later, “I never really got angry. I felt I didn’t really have time. I was tormented by the idea that I had to paint, and when I was away from Max and first with Renato, I painted immediately.”

Although she saw her mother again, this marked the definitive break from her father.

Mexico was a pole of attraction for many of these artists for several reasons. There was its association with the Russian revolutionary and founder of the Fourth International, Leon Trotsky, whom André Breton had met in exile there. It continued to offer sanctuary to political radicals. Péret, who was imprisoned in Nantes in 1940 for his political activity, went there from New York. Péret’s wife Remedios Varo became one of Carrington’s closest friends.

Some of these artists turned to an examination of Mexican myths and legends in their work, and much of Carrington’s later work was driven by her investigation of mystical systems. The magic of the stories she heard in childhood, the animal imagery and occult symbolism, fed a turn towards the mystical. In 1971 she spent time studying Buddhism from an exiled Tibetan monk.

For all that, as Marina Warner puts it, Carrington continued to follow the Surrealist notion that “life itself was far more marvellous than art, and art need only try to fix life for a moment.”

Carrington many times discussed “‘surrealist survival kits’ to enable us to get through these terrible times,” as Penelope Rosemont of the Chicago Surrealist Group records.

In Mexico Carrington met the Hungarian photographer Csizi Weisz. Weisz had left Hungary with photographer Robert Capa to work with him in Paris, and was responsible for rescuing many of his negatives when they fled. Carrington and Weisz had two children, Gabriel and Pablo. Their influence, and the development of her close collaborations with Varo and the photographer Kati Horna, enabled Carrington to develop new strands of Surrealism.

Many of her later works are marked by a domestic tenderness informed by the earlier mythological and fantastic influences and images, for example And Then We Saw the Daughters of the Minotaur (1953).

In Mexico she worked in visual arts, chiefly painting and sculpture, but the same qualities informed her work in other media. The protagonist of her warm and playful novel, The Hearing Trumpet (1976), is thought to be based on Varo.

Carrington gained growing recognition in the post-war period. Her first solo show was held in New York in 1947, and a major retrospective took place in Mexico in 1960.

Last year saw the first major show of her work in Britain for nearly 20 years. Throughout her life and work she remained consistent in her questing view that “The task of the right eye is to peer into the telescope, while the left eye peers into the microscope.”