This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Crisis in Middle East intensifies

The Middle East

The Middle EastTensions in the Middle East mounted on many fronts during this week in 1986, largely due to an increasingly aggressive posture by the US.

On January 10, 1986, the secretary of the counter-terrorism office in the US State Department, Robert Oakley, threatened to level economic sanctions against the Baathist government of Hafez al-Assad in Syria similar to those that had been imposed on Libya a week earlier over alleged links to terrorist attacks. Syria expressed shock over the threat, since it had been cooperating to free US hostages in Lebanon. Oakley praised the Iraqi government of Saddam Hussein as an example for its expulsion of the Abu Nidal Organization.

Fighting in Lebanon threatened to reignite that country’s smoldering civil war. The fascistic Christian Phalangist militia loyal to President Amin Gemayel crushed a splinter militia, the Lebanese Forces, whose leader had signed on to a Syrian-backed peace agreement that would have given more equitable representation to the nation’s Shiite and Sunni Muslims. Gemayel, an ally of Israel and the US, was meeting with Assad in Damascus when the fighting took place, in which about 200 died. In response to the actions of Gemayel, a coalition of 11 Muslim, Druze, and leftist militias began new attacks on the Phalangists.

On Sunday, January 12, an Iranian naval crew boarded a US commercial freighter as it neared the Persian Gulf. The Iranians were searching for military supplies bound for Iraq, with which it was in the midst of a bloody war. The US was also secretly supplying Iran with arms via Israel and using the money to illegally fund Contra death squads in Nicaragua.

50 years ago: Eisenhower warns of “military industrial complex”

Eisenhower

EisenhowerIn his farewell speech delivered on January 17, 1961, President Dwight Eisenhower warned the US public of the “grave implications” posed to democracy by what he termed the “military industrial complex.” The warning was particularly telling coming from Eisenhower, a longtime military man and the supreme allied commander in Europe during World War II. His successor, Democrat John F. Kennedy, had campaigned on a promise to greatly increase military spending.

While insisting on the “imperative need” that the US military “be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction,” Eisenhower noted that the “military organization today bears little relation to that known of any of my predecessors in peacetime, or, indeed, by the fighting men of World War II or Korea.”

“Until the latest of our world conflicts, the United States had no armaments industry,” he went on. “American makers of plowshares could, with time and as required, make swords as well. [But] we have been compelled to create a permanent armaments industry of vast proportions. Added to this, three and a half million men and women are directly engaged in the defense establishment. We annually spend on military security alone more than the net income of all United States corporations.

“The total influence—economic, political, even spiritual—is felt in every city, every Statehouse, every office of the Federal government.... Our toil, resources, and livelihood are all involved. So is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes.”

75 years ago: Soviet Union prepares military build-up

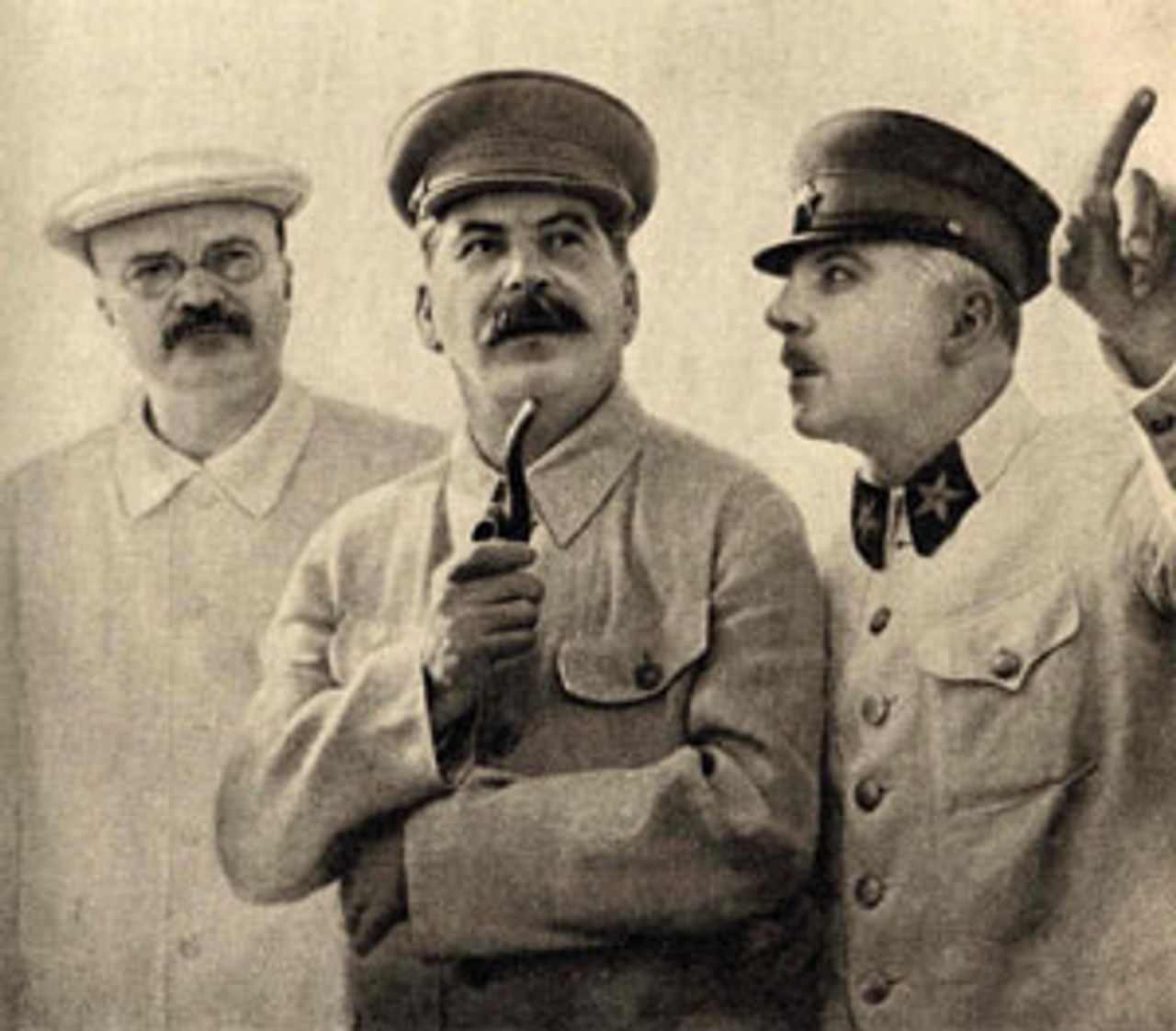

Vyacheslav Molotov, Joseph Stalin and Kliment

Vyacheslav Molotov, Joseph Stalin and KlimentVoroshilov

Soviet Prime Minister Vyacheslav Molotov on January 10, 1936, called for a massive increase in military spending to prepare for the threat posed by Nazi Germany and imperial Japan.

Molotov, with Stalin flanking him, addressed a congress of the Central Executive Committee in the Kremlin. The premier warned that Berlin and Tokyo might “break their own necks” should they move toward war, and complained that Hitler had yet to renounce his published aim of attacking the Soviet Union outlined in his blueprint for a German millenium, Mein Kampf. At the same time, Molotov stressed that the Soviet Union had sought better relations with Germany and had repeatedly appealed to Japan for a non-aggression pact. Foreign ministry spokesman Karl Radek and assistant commissar for defense Marshal Tukhachevsky echoed Molotov’s comments during the week.

In fact, the policies of the Stalinist bureaucrats had set the stage for the Soviet Union’s encirclement. The Stalin-controlled Third International had sacrificed the Chinese Communist Party and the militant workers of China to secure an alliance with the nationalist Chiang Kai-shek, thus weakening the main bulwark to Japanese aggression in the east. The Communist Party’s line in Germany of the early 1930s—including the policy of “social fascism”—had prepared the way for the victory of Hitler.

It was in fact the Stalinists’ betrayal of the revolutionary aims of 1917 that posed the greatest threat to the Soviet Union, as the exiled co-leader of the Russian Revolution, Leon Trotsky, continuously stressed. Imperialism, Trotsky explained in an article published the same week as Molotov’s speech, “sees the best pledge of the ‘normalization’ of the Soviet regime in Stalin’s offensive of extermination against the Bolshevik-Leninists and other revolutionists.”

100 years ago: US Central Bank proposed

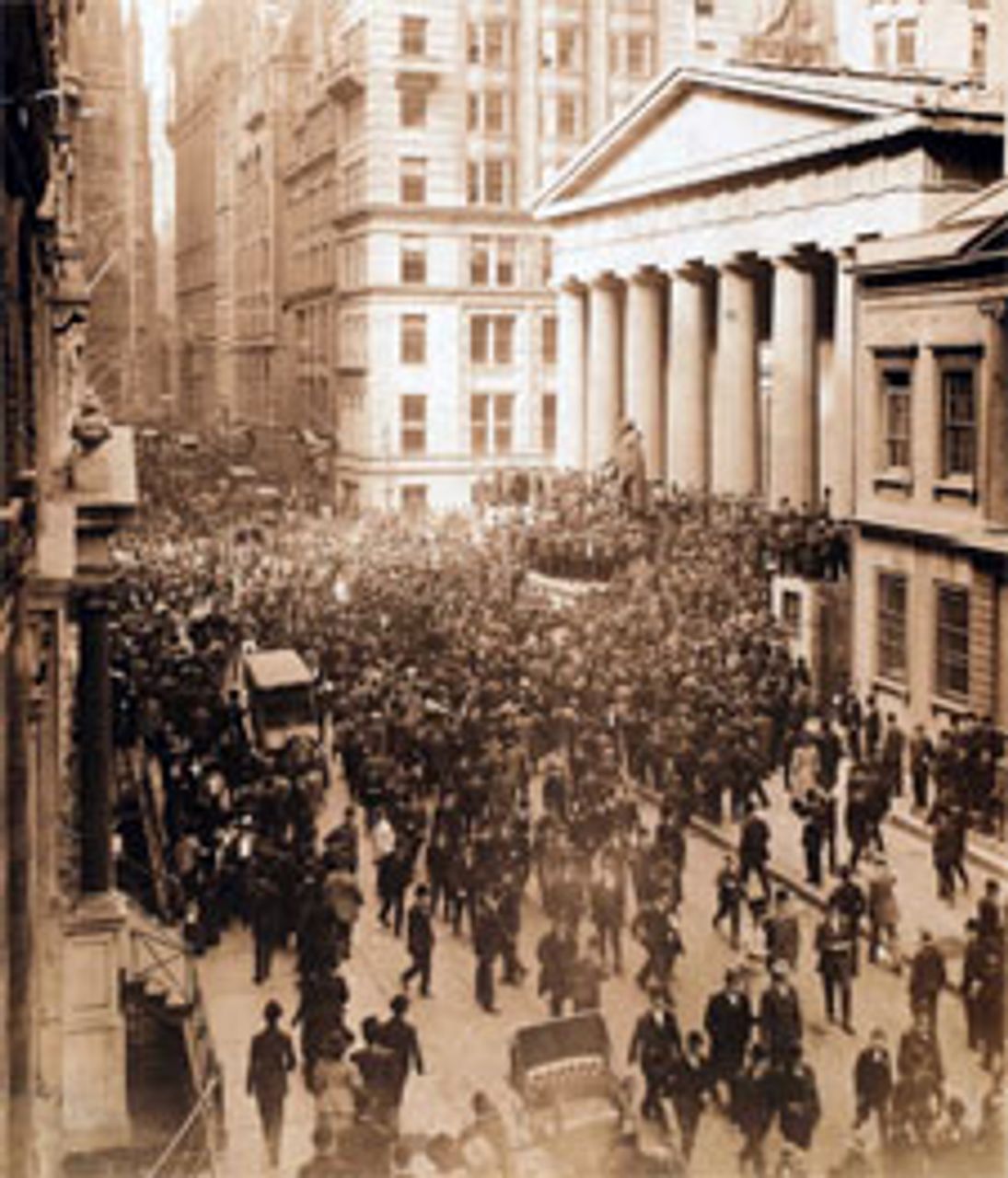

The Panic of 1907

The Panic of 1907On January 17, 1911, Senator Nelson Aldrich, in his capacity as chair of the National Monetary Commission, formally proposed the formation of a “Reserve Association of America,” which in 1913 would become, with some modifications, the Federal Reserve System. The central bank, like those already well established in Europe, would be given effective control of the money supply and interest rates for the benefit of finance capital as a whole.

The central bank proposal came in response to a series of financial crises, including the Panic of 1907, in which major banks had responded to an emerging international financial crisis—precipitated by rampant swindling in US financial circles—by closing off credit to lesser banks. This created a liquidity crisis and a cascade of bankruptcies and runs on banks and trusts.

The preeminent banker in the US, J.P. Morgan, is often given credit for stemming the Panic of 1907 by cajoling other leading financiers into following him into reopening lines of credit, and that this collusion of the finance industry to stem the panic—and save itself—provided the inspiration for the federal reserve. Treasury Secretary George Cortelyou also bowed to Morgan’s request that he place Treasury money in Wall Street banks. Morgan in fact profited immensely from the panic, eliminating rivals and absorbing the near bankrupt Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company for his flagship US Steel, with the acquiescence of President Theodore Roosevelt.

Indeed, Aldrich’s plan for a central bank had been crafted months earlier in secret conversations with a number of bankers and Morgan representative—including his deputy Benjamin Strong, who would become the first chair of the Fed—at the Jekyll Island Club in Georgia.