This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Europe-US tensions over Libya

Libya

LibyaOn January 8, 1986, the Reagan administration ordered all Libyan assets in the US frozen, but its efforts to rouse international support showed Washington’s isolation. The Western European powers, led by Italy and West Germany, publicly rejected Washington’s call for severe sanctions against the regime of Muammar al-Gaddafi. They were joined by Japan, the Islamic Conference Organization, and the Soviet bloc.

“Terrorism” was the overarching pretext the US used to justify its actions against Libya, including preparations for war. The Reagan administration had pinned terrorist airport bombings in Rome and Vienna two weeks earlier on Gaddafi, and held Libya responsible for “Palestinian terrorism” in general. Libya rejected the allegations, and Italy and Austria responded to Reagan’s assertions by stating there had been no evidence of Libyan involvement in the bombings, which killed 19 on December 27, 1986.

The supposed Libyan terror threat was also used to step up police activity in the US, with the Federal Bureau of Investigation announcing on January 7 that it would increase its surveillance of Libyan nationals residing in the US.

The European governments had much to lose in the event of a war with Libya. Italy was Libya’s largest trading partner and second leading supplier of arms after the Soviet Union. West Germany was its number two trading partner, and Libya was Austria’s second leading supplier of petroleum. Meanwhile, the US accounted for but 2 percent of Libya’s imports in 1984.

50 years ago: US breaks off diplomatic relations with Cuba

Castro at Lincoln Memorial, 1959

Castro at Lincoln Memorial, 1959On January 3, 1960, the Eisenhower administration severed all diplomatic ties with Cuba, shutting down the US embassy and bringing to a new low relations between Washington and the Castro government. John Kennedy, the Democratic president-elect, was briefed on the decision.

The move was the culmination of a series of measures taken by Washington to isolate and ultimately remove the Castro government, which came to power after toppling the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista in 1959. In the immediate aftermath of seizing power, Castro expressed interest in maintaining relations with the US, and he distanced himself from socialism. But as the US placed restrictions on Cuba―including an embargo on oil and refined petroleum products―Castro responded by nationalizing US-owned property and moving closer to the Soviet Union. On the other hand, Castro maintained stable relations with Canada.

Right-wing Cuban exiles cheered the move to cut off diplomatic ties, and loudly proclaimed they would soon be able to mount an invasion of the island. In fact, in March of 1960 the Eisenhower administration had secretly authorized the CIA training of rightist Cuban emigrés for an eventual landing and assault on the Castro government.

75 years ago: Roosevelt warns of war

Roosevelt

RooseveltIn his third State of the Union address, delivered on January 3, 1936 in the midst of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt began the process of preparing the US public for what he called “general war.”

Without naming any actual country by name, Roosevelt clearly referred to Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and imperial Japan when he referred to “nations seeking expansion, seeking the rectification of injustices springing from former wars, or seeking outlets for trade … [nations that] reverted to the old belief in the law of the sword, or to the fantastic conception that they, and they alone, are chosen to fulfill a mission and that all others among the billion and a half of human beings in the world must and shall learn from and be subject to.” In the course of the previous year, Italian forces had invaded Ethiopia on the Horn of Africa, Nazi Germany continued to rearm itself, and Japan was in advanced preparation for a full onslaught against China.

The American president presented the US as a democratic, progressive, anti-imperialist nation, at peace once more with itself and holding a position of neutrality on issues that did not affect the Americas. The reality was far different. The “New Deal” administration ultimately could find no way out of the contradictions of the Great Depression except to mobilize the idled industrial might of American capitalism to shatter its imperialist rivals in the “general war” Roosevelt prophesized.

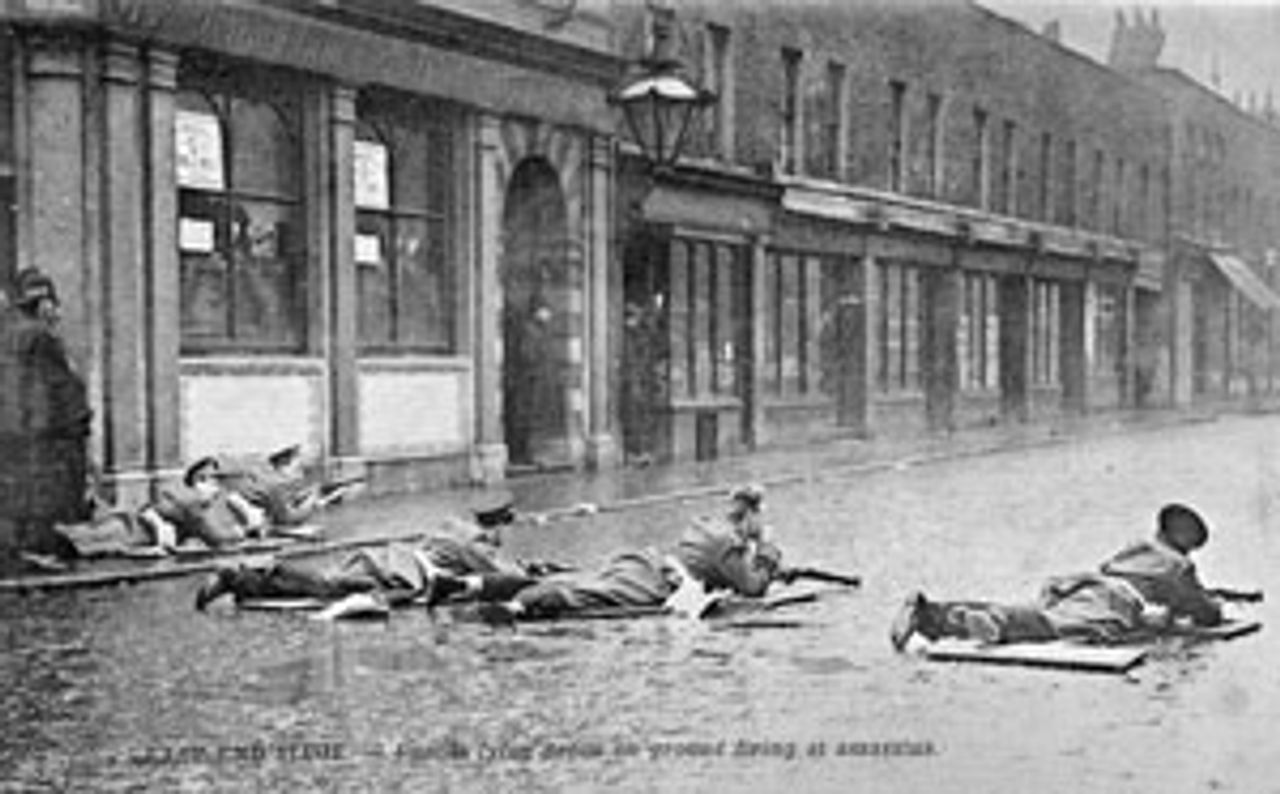

100 years ago: “Siege of Sidney Street” in London

Scots Guards opening fire in Sidney Street

Scots Guards opening fire in Sidney Street On January 3, 1911, 200 London policemen and a detachment of Scots Guards―acting at least in part under the command of Home Secretary Winston Churchill―laid siege to a house on Sidney Street in London’s East End where two or three Latvian immigrant anarchists accused of killing police officers weeks earlier were hiding. Two were killed in the military-style operation, but “Peter the Painter,” the alleged ring leader, was either not in the house or managed to escape.

The anarchists were accused of belonging to a burglary ring. On December 16, two police were killed after they encountered burglars―allegedly the anarchists―while they robbed a jewelry store. An informant later told the police that the perpetrators, including Peter the Painter, who may have been a Latvian immigrant named Peter Piatkov, were in hiding at the house on Sidney Street.

Churchill either organized in full or ultimately assumed control of the operation whose disproportionate size could only have been aimed to menace London’s working class. The Scots Guards are a unit of the British military; rapid fire Gatling guns and an artillery piece were also deployed in the operation. When the house caught fire, Churchill, by then personally on the scene, ordered away a fire brigade that had come to extinguish the blaze. Instead, Churchill ordered soldiers to keep their fire trained on the door in case the anarchists attempted to escape the flames. The charred remains of Fritz Svaars and William Sokolow were found inside, but not Peter the Painter, whose name subsequently became legendary in London and in Ireland.