John Pilger has reported on six wars, beginning in Vietnam in 1967, and produced more than 55 documentaries. His new film, The War You Don’t See, examines the media’s role in war and asks whether it has become part of the propaganda machine of the state. The documentary focuses in particular on the practice of “embedding” journalists in military units, which has helped virtually destroy independent war reporting.

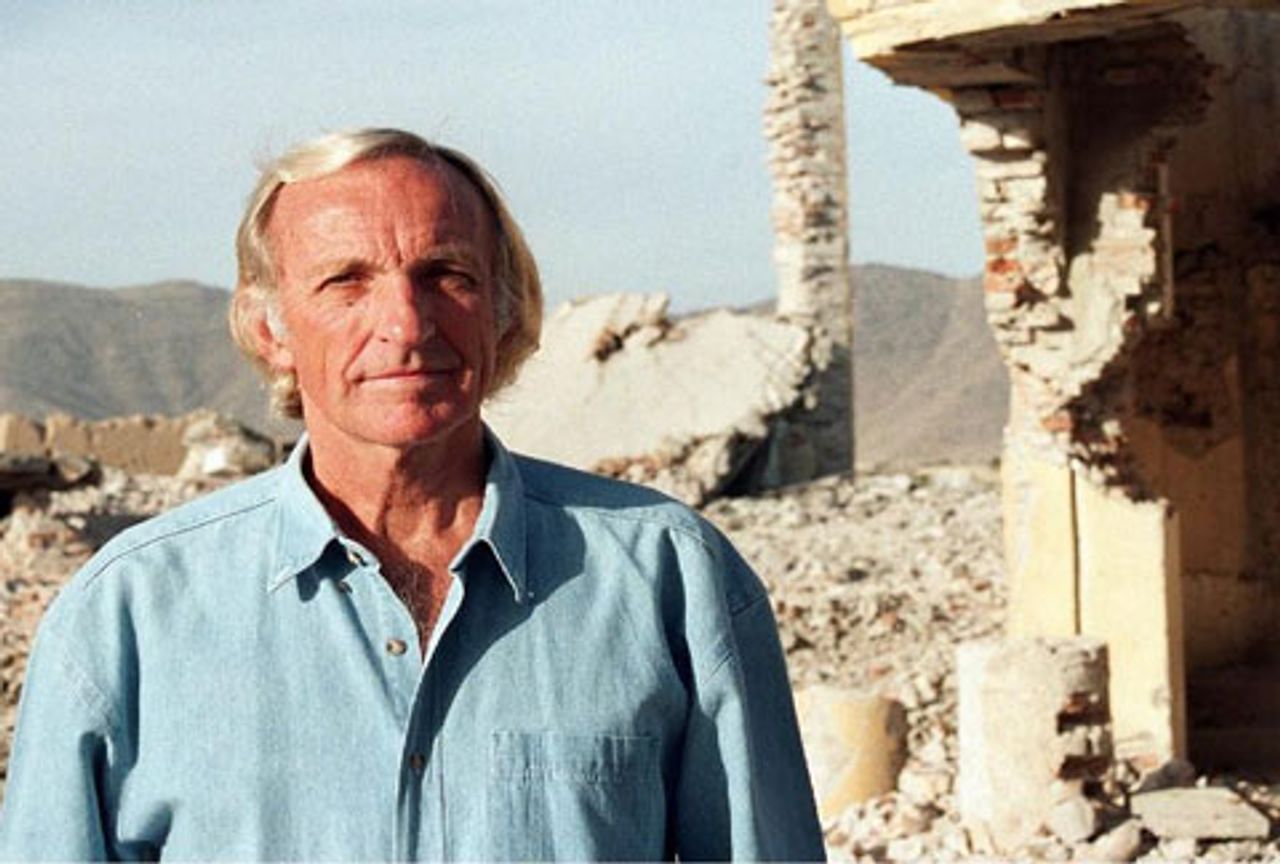

John Pilger

John PilgerThe War You Don’t See opens with the sickening video clip released by WikiLeaks earlier this year, in which US troops in an Apache gunship revel in their indiscriminate slaughter of innocent bystanders in Iraq. Pilger asks, “Why do so many journalists beat the drums of war, regardless of the lies of government, and how are crimes of war justified?”

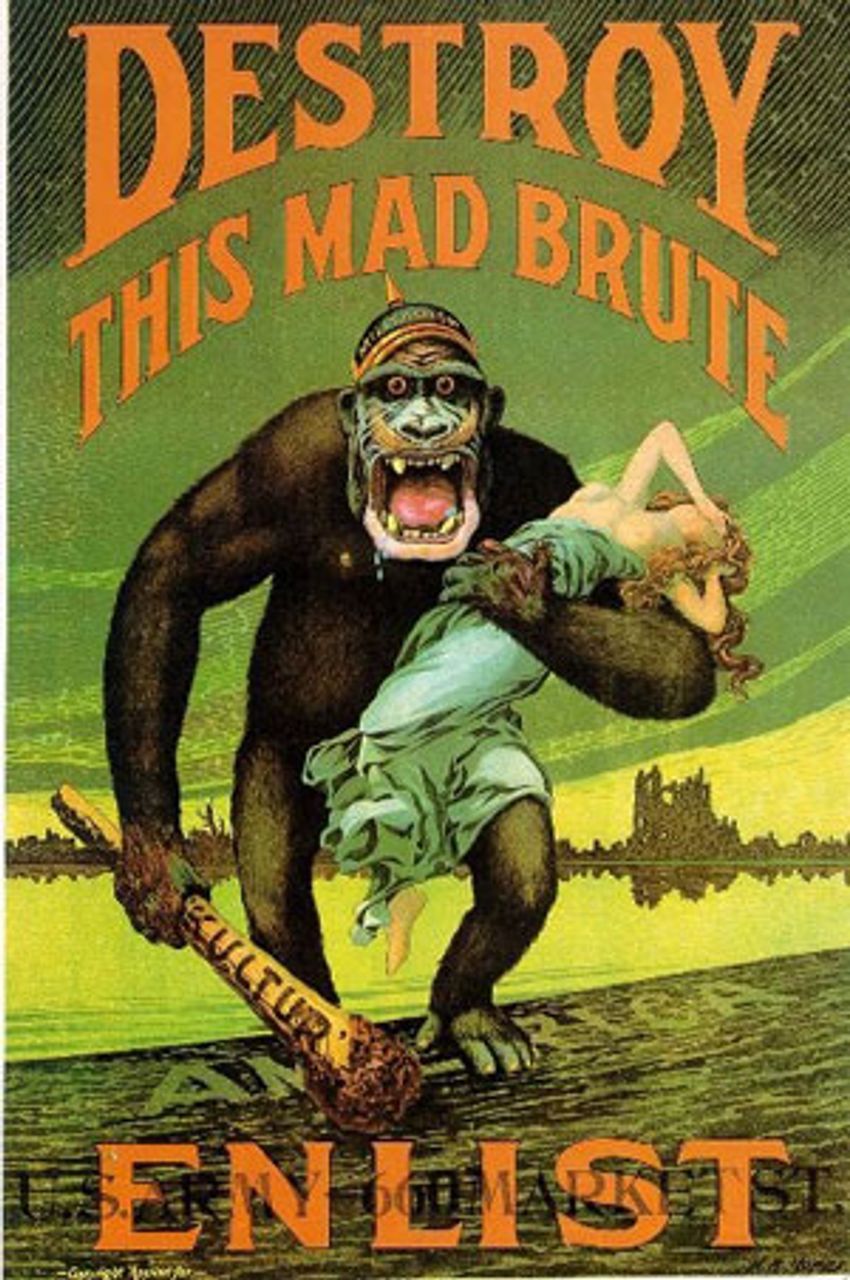

“Destroy This Mad Brute” poster, 1917

“Destroy This Mad Brute” poster, 1917Pilger traces the growing integration of the state and media back to World War One. In the US, the secretive Committee on Public Information was set up in 1917 by US President Woodrow Wilson to “sell the war to the masses”. One of its most influential members was public relations-propaganda pioneer Edward Bernays. “The intelligent manipulation of the masses is an invisible government which is the true ruling power in this country”, Bernays wrote. The “hide the facts and manipulate emotions to scare the hell out of people” philosophy lay behind First World War posters such as “Destroy this Mad Brute” (1917).

Pilger fast-forwards to 2003 and the Iraq war. The creation of illusions, he says, has come a long way since Bernays’s time. Today, the Pentagon spends $1 billion a year on such activities. US Assistant Secretary of Defence Bryan Whitman describes how the Iraq war introduced the practice of embedding and saw some 700 journalists attached to army units. He says it was necessary because the US was up against an enemy, Saddam Hussein, who was “masterful at misinformation…disinformation”.

A former CIA analyst implies it is the US that is the master of manipulation, saying that 80-90 percent of news is officially inspired and anyone who crosses the Pentagon is likely to have his or her access and sources removed.

Pilger is best when he probes top journalists, news schedulers and government officials. They hesitate and squirm as they seek to justify their capitulation to and collaboration with the lies about the Iraq war. Some show remorse. Others say, more or less, “Let’s learn the lessons and make sure it never happens again.”

Dan Rather—for more than two decades an anchorman with CBS News—admits that journalists act more often than not as mere “stenographers”, repeating uncritically what government officials say.

Rather, who once confronted Nixon in 1974 over Watergate and the elder George Bush over the Iran-Contra scandal, turned in a despicable performance on the late-night David Letterman show following 9/11. Pilger reminds him of his words, “George Bush is the president. He makes the decisions. And as an American wherever he wants me to line up, tell me where and he’ll make the call”. Rather explains this episode on camera by arguing that there is “fear in every newsroom in the country…fear of losing one’s job, being labeled unpatriotic”.

An interview with BBC World Affairs Correspondent Rageh Omaar proceeds along similar lines. Pilger questions Omaar about his role as an embedded journalist in the British advance on Basra during the invasion of Iraq. How, wonders Pilger, was it possible for BBC news reports to declare that Basra had “fallen” 17 times to the British armed forces?

Omaar replies that there is enormous pressure with 24-hour news coverage to present a story as though it is new. He makes similar remarks about the false picture given of the “liberation” of Baghdad and the phony toppling of Saddam Hussein’s statue. Omaar confesses, “I didn’t really do my job properly. I think I’d hold my hands up. One didn’t press the most uncomfortable buttons hard enough”.

Omaar speaks as well about the US attacks on the offices of Al-Jazeera in Kabul in 2001 and Baghdad in 2003. The Qatar-based media outlet was viewed by the Pentagon as broadcasting reports somewhat independent of the US-UK version of events. Omaar says the attacks were “without doubt and categorically a direct targeting to shut them [Al-Jazeera] up and possibly kill them”.

The War You Don’t See contains footage of several top British journalists—Andrew Marr, Nicholas Witchell and Mark Mardell—applauding the capture of Baghdad in virtually the same euphoric language. Reading like an official press release from the ministry of defence, Bush and Blair’s strategy, the journalists claimed, had been “vindicated”. Just as the two leaders had predicted, they continued, there had been no bloodbath and everywhere Iraqis were celebrating.

US Apache gunship targets civilians

US Apache gunship targets civiliansPilger counterposes such statements to the fact that, as a result of the war, 740,000 women have been made widows and 4.5 million people forced from their homes. Hardly any of this is reported on.

Pilger criticises erstwhile liberal newspapers such as the New York Times and the Observer for their uncritical acceptance of the “proof” that Hussein had weapons of mass destruction (WMD), presented by US Secretary of State Colin Powell’s during his notorious appearance at the United Nations in February 2003. The Observer’s David Rose said he was “nauseated, angry and ashamed” about his articles, but blamed them on the “pack of lies fed to me by a fairly sophisticated disinformation campaign”.

Pilger questions BBC Head of Newsgathering Fran Unsworth and Editor-in-Chief of ITV News David Mannion about their acceptance of the WMD claims and suggests that by their actions they helped contribute to the war drive. Unsworth tries to say she “didn’t realise until later”, but Pilger points that United Nations weapons inspector Scott Ritter was saying as early as 1998 that all chemical, biological and nuclear facilities in Iraq had been sealed up and the only UN-sanctioned research was on missiles of less than 150 kilometres range.

Both Unsworth and Mannion are probed about their biased reporting towards Israel. Why, Pilger asks, do news reports rarely call the military occupation in Palestine by its proper name and give chief propagandist Mark Regev full vent to put forward Israel’s version of events? Why did the BBC and ITV broadcast the blatantly doctored Israeli video of the storming of the Gaza flotilla in May 2010, which sought to blame the aid workers for the violence that ensued? Why did they virtually ignore the UN report six months later that noted the “unnecessary and incredible violence” inflicted by Israeli troops and the shooting of six on the ship at point-blank range?

In a feeble reply, Unsworth argues it is not the BBC’s fault that Israel has a sophisticated public relations machine and the Palestinians have no one to match Regev. Mannion replies it is not “the job of journalism to change the world”.

Former senior British foreign office official Carne Ross tells Pilger that journalists “more or less accepted our version of events,” surrounding the Iraq war, and that those who backed the official line were treated with “favouritism”, while those who didn’t were “punished”. Ross describes to Pilger his “guilt and shame” at being involved in the “major deception” used to justify the Iraq war. There were “great falsehoods, but the perpetrators are still running around”.

Pilger also presents the story of journalists who have attempted to remain independent. There is Dahr Jamail, for example, who reported on the destruction of the Iraqi city of Fallujah, where thousands were killed, over 70 percent of houses destroyed and white phosphorus bombs used against civilians (a fact denied for months by US officials). None of Jamail’s reports appeared in the mainstream American media.

And Pilger recalls Australian-born left journalist Wilfred Burchett, who refused to attend the stage-managed Japanese surrender on the USS Missouri at the end of World War Two and set off for the bombed city of Hiroshima. There he exposed the full horror of its destruction by nuclear bombing, along with official claims that nuclear radiation was harmless.

In his excellent film, Pilger also interviews Phil Shiner, a lawyer representing victims of abuse by British soldiers, and the co-founder of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, who blames the “vast sprawling industrial estate” that is becoming more secretive and uncontrolled.