The strike movement in Egypt against the dictatorship of President Hosni Mubarak broadened significantly Wednesday, with factory workers, civil servants and agricultural laborers all taking action in the greatest threat yet to the survival of the regime.

While most media attention has been focused on the confrontation at Tahrir Square in central Cairo, where tens of thousands are face to face with army tanks, popular anger has been intensifying throughout the country against unemployment, high prices and 30 years of brutal dictatorship.

There are clear signs that the youth in Tahrir Square and the factory workers are seeking unity in action against the regime. Tuesday’s massive demonstration, which brought hundreds of thousands into the streets of the capital, was combined with a call for a general strike, the first such appeal issued since the protests began in Cairo January 25.

The strike wave had already begun before that appeal was issued, but it accelerated markedly in response, signaling that the workers are going into action not only over wages, jobs, working conditions and other economic issues, but as an expression of their rising political consciousness and hostility to the Mubarak regime.

The last decade has seen an enormous growth of the Egyptian working class, as the country has been more and more integrated into the global economy, and foreign companies have made it a major target of direct investment. This in turn has led to an upsurge in the class struggle, with more than 3,000 labor disputes breaking out over the past five years. A major demand raised in many struggles is to lift the Egyptian minimum wage, which has been frozen at the level of $6 a day since 1984.

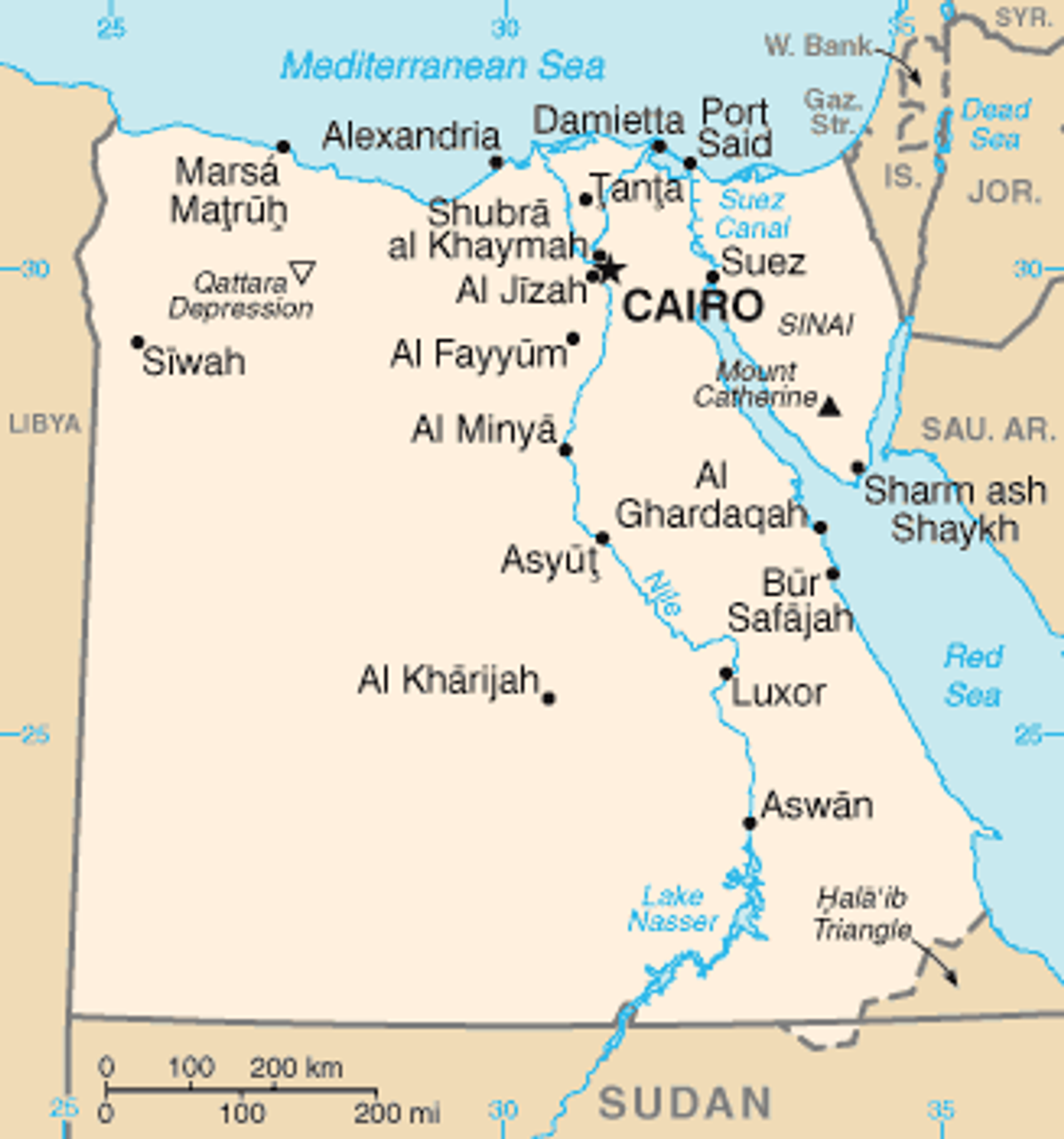

New sections of workers joining the strike movement Tuesday night and Wednesday, according to press reports, included railway technicians in Bani Suweif, 2,000 workers at the Sigma pharmaceutical company in Quesna, in the Nile delta, and tens of thousands of public service workers in Cairo, including employees of the state health ministry, state electricity workers and public transportation workers.

One of the most explosive and strategically important areas is along the Suez Canal. Thousands of workers at the southern end of the canal, in the city of Suez, went into the second day of a strike against several state-owned enterprises, including textile mills, ship repair yards, sanitation services and a medicine bottle factory.

Two thousand employees of the Suez Canal went on strike Wednesday, but the transit of ships through the canal has not yet been affected. Hundreds of unemployed youth picketed a petroleum company demanding jobs, and the French-owned Lafarge cement factory was also hit by a strike.

A Suez shipyard worker told the press that 1,500 workers had begun a sit-in strike over management’s refusal to provide financial support for workers suffering from chronic work-related illnesses. Another 500 workers were sitting in at a steel factory and blocking nearby roads, citing low pay and persistent pollution that sickens them.

At the northern end of the canal, Port Said, a city of 600,000 on the Mediterranean coast, hundreds of impoverished slum dwellers attacked and set fire to the administration building of the local governor, protesting the failure to build promised low-cost housing. Police did not intervene as demonstrators set up tents in the central Martyrs Square, in imitation of the occupation of Tahrir Square in Cairo.

The British newspaper Guardian reported, “Cities across the Nile delta north of Cairo, those far to the south and others to the east have also had streets filled with demonstrators demanding Mubarak go.” Mohamed Sabaie, a young unemployed protester in the Nile delta city of Tanta, told Reuters News Agency, “I want Mubarak to leave, I want all this system to leave, this system has all kinds of corruption.”

In Alexandria, the country’s second largest city and the biggest in the delta, an estimate 18,000 people demonstrated against the Mubarak government in the main square.

South of Cairo, in the heavily populated strip that stretches for hundreds of miles along the Nile, there were more demonstrations and some violent clashes. In Luxor, a tourist center, thousands of workers marched to demand government benefits to make up for income lost due to the sudden collapse of tourist traffic.

In Aswan, 5,000 unemployed youth attacked a government building, demanding the removal of the governor. In Assyut, 8,000 people chanted anti-Mubarak slogans, blocked the main highway and railway to Cairo with palm trees, demanding bread and the ouster of the dictatorship. When the local governor attempted to speak to the crowd, they stoned his van, smashed its windows and forced him to flee.

In two towns in the far south and southwest, there were media reports of massacres on Tuesday. The Egyptian newspaper Youm7 reported an attack by police in Al-Wadi al-Jadid, where two people were killed and 100 injured. There was also a report that police fired on protesters in El Khargo, 240 miles south of Cairo, killing three people. In the second town, demonstrators returned Wednesday and burned police stations and other government buildings in retaliation for the bloodshed.

The majority of Egypt’s population still lives in the countryside, tilling the land under the domination of a semi-feudal landlord class. Reuters News Agency carried one of the few reports on unrest among these brutally oppressed agricultural laborers and small farmers, noting that “rural Egypt is restless for change,” and quoting one farmer near Tanta, in the Nile delta, who said, “The revolution is good.”

The report continues: “Scraping a meagre living from the land, farmers and rural workers in Egypt's agricultural heartland have watched the largely urban uprising that has shaken the ruling system and many back the web-savvy youths who galvanised the nation. A few have turned up in Cairo in their galabiyas, the robes worn in the fields, although most are too busy trying to feed their families. But many believe it is time for a new era.”

In the capital, Tuesday’s enormous mobilization of as many as one million people greatly expanded the scope of the movement against the Mubarak government. The demonstrators spread well beyond Tahrir Square, and they were joined by sections of government workers who also took to the streets.

Hundreds of state electricity workers rallied in front of the South Cairo Electricity company, demanding its director be removed. Hundreds of Health Ministry workers walked out, demanding higher wages and the resignation of corrupt officials, as did dozens of workers at the state museum.

One press account described Health Ministry workers denouncing the plundering of their country by the regime, chanting, “O Mubarak, tell us where you get $70 billion dollars?”

Other accounts described government telecommunications workers in Cairo walking out in their thousands, chanting for “wages,” “freedom” and “rights.”

Demonstrators from Tahrir Square marched to the parliament building and forced it to close on Wednesday, staging a sit-in in front of the cordon of troops and tanks set up by the Egyptian military. Mohammed Sobhi, a 19-year-old student at Al-Azhar university, told a reporter, “The people did not elect this parliament. We want the entire regime to fall, not just the president, because everything under him is corrupt.”

Some 500 members of the Egyptian media issued a statement denouncing the official press and television coverage of the protest movement and demanding the resignation of the minister of information, Anas El-Fikki, for “falsification of facts and lack of transparency in the coverage of the popular anti-Mubarak revolt led by Egyptian youth.”

There is no doubt that the widespread eruption of working class struggle is the principal factor that has, up to now, prevented the Mubarak government and its main international sponsor, the United States, from going forward with plans to crush the demonstrators in Tahrir Square by force.

Neither Mubarak, vice president Omar Suleiman, nor the Obama administration can be confident of the outcome of a direct attempt to drown the popular movement in blood. At the same time, however, they are impelled to strike preemptively, to forestall the prospect of the linking up of the protest movement, primarily made up of young people, with the working class.

It was precisely to prevent such a connection that the Chinese Stalinist regime carried out its massacre in Tiananmen Square in June 1989. The maneuvers of the Mubarak regime—aided and abetted by the Obama administration—are aimed at preparing the conditions for such an attack.

The most ominous warning came from vice president Suleiman, the man backed by both the United States and Israel to head a “transition” regime if Mubarak is forced to step down. Suleiman declared on Tuesday that the only alternative to the negotiations proffered by the government—based on Mubarak finishing out his term as president—would be a “coup.” He then added: “We don’t want to deal with Egyptian society with police tools.”

Suleiman added that the government “can’t put up with continued protests” for a lengthy period, and declared that there will be “no ending of the regime” by Mubarak’s immediate departure. In a media briefing, Suleiman singled out the calls by some protest leaders for a wider campaign of strikes and civil disobedience as “very dangerous.”

Meanwhile, at least 500 people who were arrested during the first two weeks of the protests remain unaccounted for, according to the Egyptian Organization for Human Rights.

The great danger is that the mass movement in Egypt remains under the political tutelage of bourgeois elements, including not only the Muslim Brotherhood, but liberal parties like Wafd and Ghad, and figures such as Mohammed ElBaradei, the former UN arms control official.

What is urgently required is the building of a new revolutionary leadership in the working class, based on a perspective of mobilizing the urban and rural masses in a struggle for power, to carry out a socialist program.