Abstract Expressionist New York: Masterpieces from the Museum of Modern Art, May 28 to September 4, 2011; Painting on Paper: The Drawings of Robert Motherwell, June 25 to December 11, 2011, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

With 111 paintings, sculpture, drawing, prints and photographs, Abstract Expressionist New York: Masterpieces from the Museum of Modern Art, at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), contains only a small portion of the collection held by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Nonetheless the exhibition faithfully conveys a sense of what is known as the “New York School,” a significant post-World War II artistic movement.

Alongside the show of material from the Modern, the AGO has put together from its own collection an exhibition of drawings and paintings on paper by a key figure in Abstract Expressionism, Robert Motherwell (1915-1991), an artist who wrote and spoke extensively on the school’s theory and practice.

In addition to Motherwell, some of the more prominently represented artists include Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Lee Krasner, Arshile Gorky, Franz Kline and Louise Bourgeois.

Mark Rothko, 1949

Mark Rothko, 1949[Photo credit: The Museum of Modern

Art, Department of Imaging Services]

Abstract Expression as a school of painting distinguished by its large-scale, nonrepresentational imagery may defy easy interpretation, but a consideration of its social and intellectual origins, partially provided by explanatory panels throughout the current exhibit, offers some important insight.

One returns again and again to the postwar period, in an effort to sift through and sort out the artistic developments, trends and moods, many of which continue to have an influence down to our day. For the American artist in particular, social reality presented itself as an extremely contradictory phenomenon. The ‘war for democracy’ and against fascism was over, the US and its allies having triumphed. Economic life revived, and living standards would rise. The American left, in the form of the Communist Party and its periphery, promised great things from the Democratic Party, the party of Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Yet this falsely optimistic mood would rapidly dissipate. The atomic bombing of Japanese cities, the onset of the Cold War, the dramatic shift to the right by the American establishment in 1947-48, the purges of left-wingers in the unions and the entertainment industry, the anticommunist hysteria, the overall atmosphere of conformism and fear … to say the least, the artists and intellectuals were caught unawares by these developments.

Joan Mitchell, 1957 [Photo credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, Thomas Griesel]

Joan Mitchell, 1957 [Photo credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services, Thomas Griesel]How was the contemporary artist, cut off for the most part from a left-wing analysis of all this (as he or she had not been in the late 1930s), to make sense of the new realities?

As one of the AGO exhibition panels explains, “This generation had just lived through the Great Depression and the horrors of World War II, including the Holocaust and the dropping of the atomic bomb … They sought to invent art that would reassert the highest ideals of humankind, create a new beginning and prove human beings capable of greatness and beauty.”

I have for some time been an admirer of many of these artists, particularly Bourgeois, Motherwell and Rothko. With the passage of more than 60 years since the New York School arose, during which time several generations of their cultural descendants have reached maturity and beyond, it seems not only possible but necessary to continue working at a fuller appraisal and one that, if possible, goes beyond matters of personal taste.

Shift to New York

The Second World War and postwar period witnessed a geographic and aesthetic shift in the avant-garde in modern art from Europe to America, a shift distinguished by a marked turn away from representation towards high abstraction in its fullest and most finished form, most particularly in the paintings of the New York School.

Abstraction in some fashion was an almost inevitable development in modern art. That it found such extreme expression in the aftermath of some of the greatest horrors in human history, however, and involved such a deliberate rejection of any concrete presentation of the world as preached and practiced by the New York School, sheds light on both the artists’ difficulties and the degree to which their work was a response to these events.

In the writings of figures such as Motherwell, one finds a grappling with some of these issues and this history, and with the relationship of art and artists to the world. At one point he observed, “Abstract art is an effort to close the void that modern men feel.” Existentialism and other bleak intellectual trends no doubt had an impact on the New York artists.

Naturally, one must weigh the sometimes lofty goals the artists set for themselves against what they achieved.

Standing before the somber expanse of one of Mark Rothko paintings, for example, the viewer is almost overwhelmed by emotion for a generation scarred by fascism and war, so palpably expressed in his work. To some degree this is also true in regard to the other artists’ work shown here, but Rothko’s paintings, which are only sampled in this exhibit, stand apart in their truthful simplicity. Powerfully compassionate, his images are a deep lament, evoking a sense of loss that ultimately consumed the artist who, in later years, took his own life.

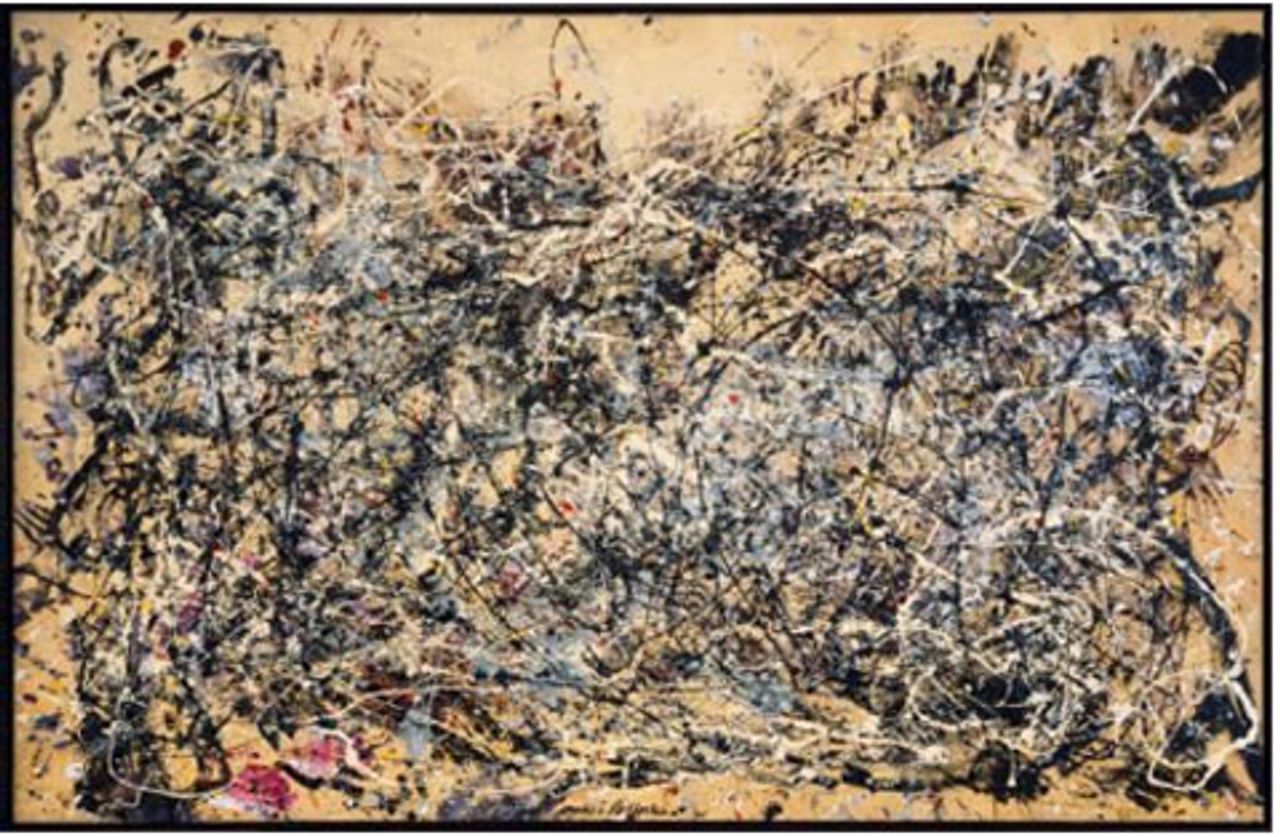

Jackson Pollock, 1948 [Photo Credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services]

Jackson Pollock, 1948 [Photo Credit: The Museum of Modern Art, Department of Imaging Services]The paintings of Jackson Pollock present their own peculiar problems. The range of work shown here reveals a breadth of style that evolved unevenly, leading up to his well known “drip paintings.” It is his less abstract if less innovative paintings, however, such as “Easter and the Totem” or “Stenographic Figure” that, in my opinion, reveal a more meaningful engagement with his medium and with the world.

In his exuberant and angry presentation of semi-abstract forms, such as “Woman, I,” Willem de Kooning provides a bridge between the figurative and the abstract, although the distinction in his case is not always helpful or even accurate. Certainly many contemporary painters refer to de Kooning as a primary influence and his work has spawned a certain following, but here too one feels the artist caught in something of an aesthetic and intellectual cul-de-sac.

The New York School artists rejected the crudities of Stalinist “socialist realism” and similar dishonest, anti-artistic trends, but wasn’t there the danger that in reducing art to the individual artist’s subjective experience alone, that they were throwing the baby out with the bathwater and ultimately cutting themselves off from the source of important artistic work, the aesthetic confrontation with the objective world of nature, society and human relationships?

As impressive and even moving as many of these works can be, and notwithstanding the astronomical value placed on much of this work by the art market, their greater significance remains to be established.

The problem of Motherwell

Robert Motherwell was not only a prolific artist until his death two decades ago, but also gained recognition as a writer and teacher on Abstract Expressionism. In his early writing he advocated a significant role for art and artists as allies and even leaders in the struggle for revolutionary social change. And while some of these observations were insightful, under the weight of events, Motherwell came to repudiate the optimism he once held about the bond between art and social life.

One painting from the series he entitled “Elegy to the Spanish Republic” (1965-67) is included in the AGO exhibition. A classic Motherwell image, featuring his trademark large black ovals pushing dark yellow shapes at the edges and imparting feelings of a dark strength and tenderness, it is among his most moving works. As the title indicates, and notwithstanding a growing skepticism, he continued until the end of his life to feel great sympathy for potentially emancipatory struggles such as the Spanish Revolution.

Extolling the combative spirit of the movement he helped to develop, Motherwell once declared that, “Abstract Expressionism was the first American art that was filled with anger as well as beauty.” Although he continued to champion abstraction in art, in his own way he acknowledged that it could represent a retreat in the face of social reaction and political disappointment. “Until there is a radical revolution in the values of modern society, we may look for highly formal art to continue,” he commented, tellingly.

Furthermore, although the artist continued to assert that art could only be truly understood and develop on the basis of an internationalist outlook, he did grow increasingly conservative politically. Under the influence of the Cold War, and his own relatively privileged position, Motherwell came to view the prospect of socialism as incompatible with the supposed freedom of the artist. He justified his abandonment of explicitly left-wing views by claiming that “The middle-class is decaying, and as a conscious entity the working-class does not exist.”

What hope he saw then lay in the activity of the individual, the artist. Defending the trend toward increasing abstraction in art, Motherwell argued that, “now artists especially value personal liberty because they do not find positive liberties in the concrete character of the modern state.”

In short, the artist fell back on rather banal, anti-communist conceptions, so popular in the academic and artistic worlds in Cold War America, counterposing all too easily and self-servingly artistic and social aspirations. He argued, for example, that “Criticism moves in a false direction, as does art, when it aspires to be a social science,” as though any conscientious critic or artist would propose such a thing. Moreover, he asserted that art could not be rationally understood: “[M]ake no mistake, abstract art is a form of mysticism.” Not a very helpful conclusion to reach.

An art of lost hopes

Initially, the leading artists of the New York School—nearly all of whom had been involved in left-wing politics (Communist Party, the Trotskyist movement, anarchism) in the late 1930s—did not view their effort as a largely personal struggle or merely an exploration of new forms, but on the contrary as a liberating means by which they might be united with broader social struggles and currents. The most penetrating saw their work as socially vital, drawing on the influence of the surrealists with whom many of them, including Motherwell, had studied and worked throughout the 1930s and into the war period.

The idea of abstract imagery as somehow divorced from social reality and the concrete actuality of life gave rise to such notions as ‘pure’ form and color advanced by some of Motherwell’s contemporaries, but which he opposed. On the contrary, he argued that, “Any red (for example) is rooted in blood, glass, wine, hunters’ caps, and a thousand other concrete phenomena.”

The artists’ unfavorable historical situation and the conditions of official hostility toward creativity and protest within which they worked in the US in the late 1940s and early 1950s help explain why they came to see formal innovation as their greatest contribution. Interestingly, Motherwell himself had warned in 1946, “the most common error among the whole-hearted abstractionists nowadays is to mistake the medium for an end in itself instead of a means.” However, even the best of intentions, as in his case, were defeated by the circumstances of the time.

Working through the repressive McCarthyite period, the New York School artists were not only frustrated in their aim of making their work socially relevant, but saw it subverted and employed for reactionary political ends. As one of the panels in the AGO show explains, “It was in the midst of this atmosphere of hyper-patriotism that Abstract Expressionism was promoted as a symbol of American cultural freedom, in contrast to the state repression of Soviet Russia.”

Unquestionably, the artists of this school brought to bear great talent and conviction to their work. They believed deeply and even heroically in the importance of art, but the problems they confronted, originating outside the artistic sphere, lend to their work an air of melancholy, if not tragedy. Indeed, one gains a stronger sense from the exhibition and a consideration of their objective situation why so many of the artists of this school came to a sad end through drugs or alcohol, or in some cases suicide.

On balance, one can argue that Abstract Expressionism represents the culmination of a certain line of development or tendency in modern art. However, modern art itself cannot be honestly discussed outside an appreciation of the tumultuous character of the 20th century, during which so many artistic schools “follow[ed] each other without reaching a complete development.” (Trotsky)

Despite the seriousness and imagination of the finest New York School representatives, the art of the trend speaks to something of an impasse, ultimately irresolvable within the limits that the artists understood themselves to be working.

It may be tempting to speculate as to whether the art of this school will live on in the future as a living force or primarily a historical curiosity, but the question may be an academic one. It doesn’t seem likely that it is simply the prevailing cultural stagnation that directs us toward its beauty and depth of commitment.