This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Chernobyl nuclear disaster

Chernobyl nuclear power plant

Chernobyl nuclear power plantOn April 26, 1986, an explosion and fire took place at the Chernobyl nuclear power complex in the Soviet Socialist Republic of the Ukraine, releasing massive quantities of radioactive material into the atmosphere that spread over all of Belarus and much of the Ukraine, Russia and Europe.

The disaster was precipitated by an experiment that began on April 25 to test an alternate means of power supply to the core cooling system, needed to contain high temperatures in the event of a power outage. Due to inadequate equipment, mismanagement and human error, the test created a nuclear reaction that escaped the control of the night shift workers on staff, leading to explosions that exposed the reactor.

The Soviet Union blocked news of the disaster from the population until a few days later, when radiation was found on the clothes of workers at a Swedish nuclear power plant about 800 miles away. Though the Gorbachev government attempted to minimize the situation in public pronouncements, the disaster response was one of the largest in human history. With fears that an uncontrollable nuclear reaction could take place, thousands of tons of sand, lead and boric acid were dropped from helicopters over the reactor. By December,1986, about 250,000 workers had been involved in the construction of a giant sarcophagus over the destroyed plant. Two nearby towns were abandoned completely.

The number of those killed remains in dispute. Thirty-one plant workers and firefighters died within three weeks from radiation poisoning. Estimates supported by the International Atomic Energy Association and the World Health Organization put the number of those who died due to health complications resulting from the explosion at fewer than 10,000. However, a team of Russian scientists led by Alexey Yablokov, head of the Russian Academy of Sciences under Gorbachev, in 2007 asserted that nearly 1 million “excess deaths” in the former Soviet Union and Europe took place as a result of the disaster.

50 years ago: UAW head calls for shorter work week

Walter Reuther

Walter ReutherOn April 27, 1961, United Auto Workers President Walter Reuther issued a call for an adjustable work week to combat high unemployment. The proposal would have shrunk the work week, at full wages, when national unemployment hit a certain threshold. Reuther said that the funds for the program could be realized by levying a 1 percent payroll tax on employers. The unemployment rate was then relatively high for the 1950s and 1960s, at 7 percent.

Under the plan to adjust the Fair Labor Standards Act if unemployment were to rise above 2 or 2.5 percent, the work week would automatically be curtailed. As the unemployment rate rose higher, the work week would be shortened accordingly. Employers who defied the law would be forced to pay their workers overtime from 38 hours per week.

Reuther delivered the address in Detroit at a special collective bargaining meeting of the 1.2 million-member UAW, then the most powerful union in the US. He criticized President Kennedy, whom the UAW had helped to elect, for opposing a shorter work week on the grounds that it would slacken production. “What about the 5.6 million unemployed workers who would like to work 40 hours but aren’t given one hour of work a week?” Reuther asked.

“It [the president’s program] does not deal with the basic structural weaknesses within the American economy out of which we have had three recessions in eight years,” Reuther said, “We need deep economic surgery in the American economy or we are going to go from recession to recession.”

In advancing the proposal, Reuther was fending off even more far-reaching demands from the rank and file in advance of contract talks with the Big Three US auto companies. At the UAW convention, he reportedly fought against demands to reduce the work week to 30 hours at full pay and establish 60 as the age of retirement.

The guiding principles of the post-war unions—anticommunism and the defense of American business interests on a global scale—were already revealing their reactionary implications in 1961. Days before Reuther’s Detroit speech, the UAW head had met with AFL-CIO President George Meany in Washington. Five-and-a-half years after the two men had led the merger of the industrial (CIO) and craft (AFL) unions, overall federation membership had declined by 2.5 million. Industrial workers were being displaced and vast sectors of the economy, including almost all of the US South, remained unorganized.

75 years ago: French elections point toward revolution

Leon Blum

Leon BlumFrench parliamentary elections held on April 26, 1936 signaled a sharp turn to the left by the French working class and a general diminution in support for parties that occupied the center of the political spectrum. The elections resulted in the formation of a Popular Front government headed by the reformist socialist Leon Blum.

The French Communist Party nearly doubled its vote from the 1932 elections, winning 15.26 percent. The social democrats saw their vote dip slightly, from 20.51 percent to 19.86 percent. The Radicals, the party of the reform bourgeoisie, saw its share of the vote fall by nearly 5 percent, from 19.18 percent to 14.45 percent. The parties of the right saw their vote decline to 42.7 percent of the electorate from 45.9 percent in 1932.

Leon Trotsky, recently driven from his exile in France to Norway, said that the election results demonstrated that the vote was “not in favour of the People’s Front Policy, but against it.” The real aim of the Popular Front, Trotsky wrote, was not to advance the interests of the French working class, but to subordinate it to the desire of Moscow to conclude an alliance with the French bourgeoisie against Hitler’s Germany.

The entire aim of the Popular Front campaign, Trotsky wrote, was to convince workers that “complete salvation lies...in the [Radical] ministry of Daladier.”

“How did the masses respond?” Trotsky asked. “When one-and-a-half million voters cast their ballots for the Communists, the majority of them mean to say thereby: ‘We want you to do the same thing in France that the Russian Bolsheviks did in their country in October, 1917.’”

Trotsky also noted the repudiation of the socialist splinter groups that were gravitating toward the Radicals. “The masses have discarded the group that was the most systematic and resolute, the loudest and the most outspoken in advocating an alliance with the bourgeoisie.”

Finally, he noted the movement of the petty-bourgeois layers away from the Radicals and toward the Socialists, and the movement of the workers and poor peasants away from the Socialists and toward the Communists. In other words, a political regroupment was “taking place along the class axes and not along the artificial line of the ‘People’s Front.’”

Trostky sensed that France had entered a period of social revolution that would not be decided in parliament. With a strike wave emerging that would soon lead to a massive general strike, the leader of the Fourth International warned that the struggle would be “consummated either in the greatest of victories or the most ghastly of defeats.” The decisive question was the need to break the masses from the Stalinists and Socialists who, as the crisis deepened, redoubled their efforts to block the revolution.

100 years ago: France sends forces to Morocco, inciting crisis in Europe

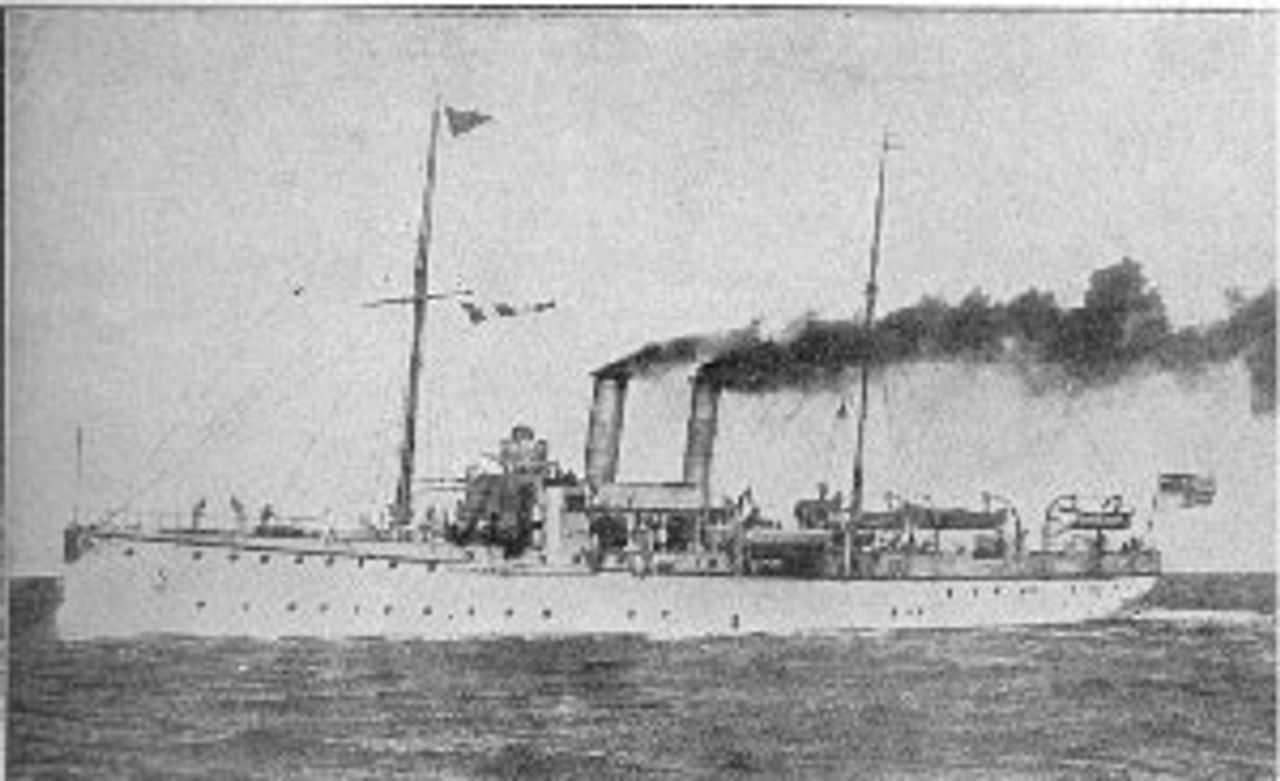

German gunboat Panther in Moroccan waters, 1906

German gunboat Panther in Moroccan waters, 1906On April 27, 1911, France notified the European powers participating in the Algeciras Conference that it was sending a battalion to the Moroccan city of Fez in the name of protecting European lives against civil unrest. In fact, the operation’s aim was to prop up the Sultan Abdelhafid, who was at that point besieged in his Fez palace by a popular rebellion.

The incident set off the second crisis in five years over Morocco between Germany, on one side, and France and Britain, on the other. In the first Moroccan crisis, in 1905, Germany determined to test Britain’s interest in backing up France’s aggrandizement in Africa. France had earlier concluded secret treaties with Italy (1900) and Britain and Spain (1904) recognizing its right to Morocco.

German opposition, which included Kaiser Wilhelm giving a speech in Tangier calling for Moroccan independence, provoked a crisis that saw France order troops to the German border and Germany issue a call-up for military reserves. The situation was temporarily defused almost entirely in France’s favor via a conference headed by US President Theodore Roosevelt. At the Algeciras Conference in Spain, all the European powers save Austria-Hungary backed the French. Germany was totally isolated.

By 1911, France was moving toward putting Morocco under the status of protectorate, while granting certain concessions to Spain. The rebellion against Abdelhafid provided the pretext.

Once again, Germany challenged the French maneuver, sending the battleship Panther to Morocco’s Atlantic Coast in the summer. This time the Kaiserreich acceded to French control of Morocco in exchange for a territorial concession in the French Congo. France once again enjoyed the vigorous backing of Britain and Russia.