Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould opens soon in a number of US cities. This comment appeared as part of coverage of the Toronto film festival in 2009.

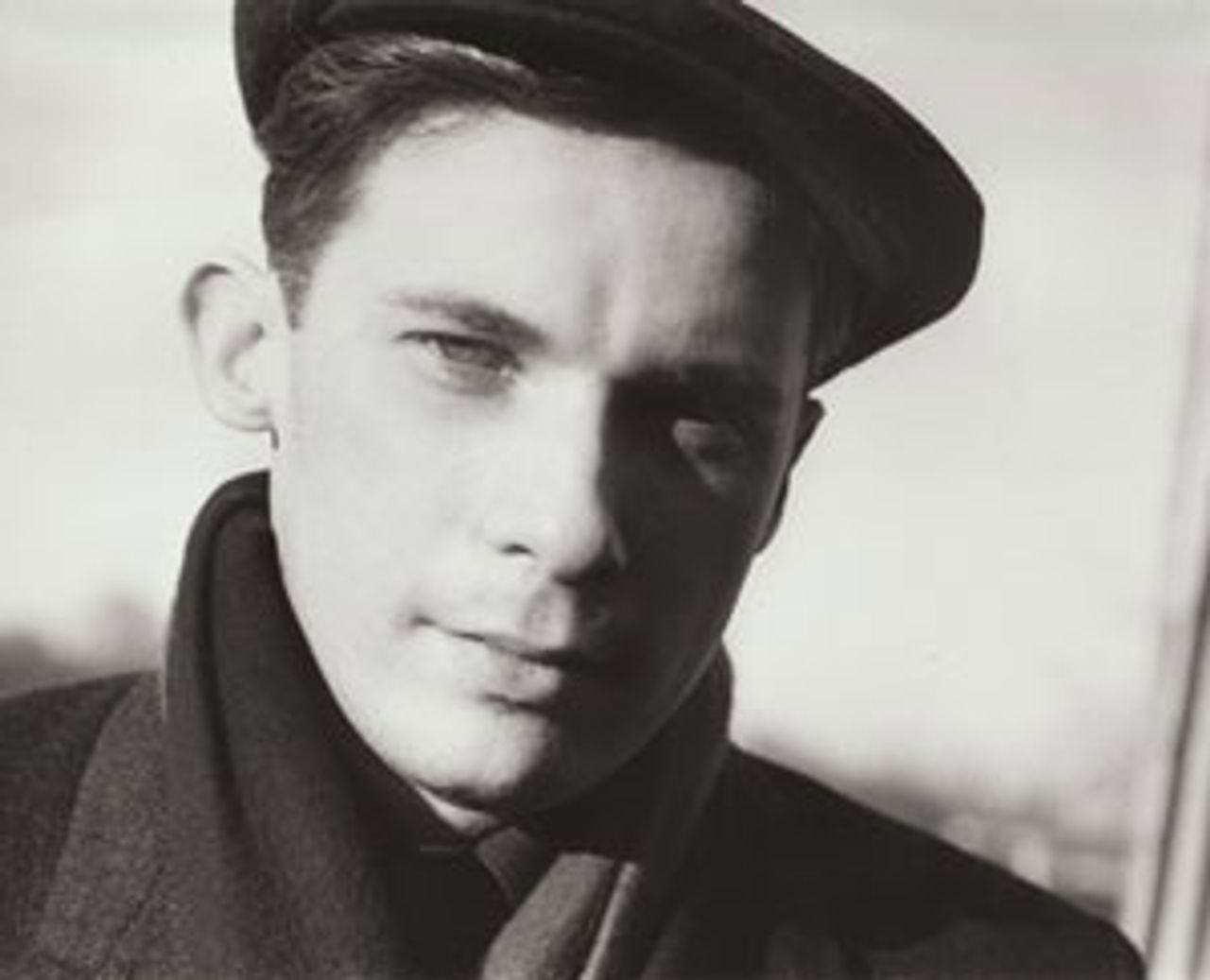

Glenn Gould

Glenn Gould

Genius Within: The Inner Life of Glenn Gould by Canadian documentarians Michéle Hozer and Peter Raymont is a compilation of previously unseen footage of Gould, as well as hundreds of photographs and excerpts of private home and studio recordings. The film’s main talking heads include Cornelia Foss (painter and wife of Lukas Foss, the prominent composer, pianist and conductor); Roxolana Roslak, the Hungarian soprano; pop-singer Petula Clark; and Vladimir Ashkenazy, the Russian conductor and pianist, to name a few.

Gould (1932-1982), one of the great pianists of the twentieth century, was highly eccentric and reclusive. The documentary traces his life and career, whose highlights include the history-making eight-concert tour in Moscow and Leningrad in 1957, in which Gould performed Bach—a composer seen as too connected to religion by the philistine Stalinist bureaucracy—to a wildly enthusiastic public. A photograph of Gould and the Soviet pianist Sviatoslav Richter records the meeting of two supreme musicians.

Another seminal event treated in the film is the 1962 New York Philharmonic concert, viewed as one of the orchestra’s most controversial. Remarks made by conductor Leonard Bernstein in introducing Gould are famous: “Don’t be frightened. Mr. Gould is here. … You are about to hear a rather, shall I say, unorthodox performance of the Brahms D Minor Concerto, a performance distinctly different from any I’ve ever heard, or dreamt of for that matter. … But the age-old question still remains: ‘In a concerto, who is the boss, the soloist or the conductor?’ … [W]e can all learn something from this extraordinary artist, who is a thinking performer.”

Gould’s five-year affair with Cornelia Foss, which only recently became public (her husband, composer, conductor and pianist Lukas Foss, died in February 2009), is one of the film’s preoccupations. Foss speaks fondly of Gould—as do her children. Gould was an admirer of her husband’s musicianship. The families of both Cornelia and Lukas had fled Nazi Germany.

Genius Within takes up Gould’s decision to quit public performance for the recording studio in 1964 more or less at the height of his career. Emotional factors aside, the Toronto-born pianist saw the relationship of a concert performer to the audience as akin to that of a bullfighter to his spectators. The metaphor was not meant approvingly. He felt that recording was a more democratic, do-it-yourself technology, a sentiment ahead of its time.

Says Cornelia Foss: “Anything pretentious made him ill,” and the desire to shun celebrity entered into his decision to quit the stage. The relationship between Foss and Gould ended as the latter descended into paranoia and abuse of prescription medication. Recalling Gould as a “Renaissance Man,” the film asks but never answers the question: What in the Gould mystique continues to captivate beyond the genius of his music?

Genius Within refers in vague terms to the 1960s and raises interesting questions about a man who took his art seriously—to a crippling degree. But more could have been done to connect, in a complex fashion, the artist’s contrarian streak with the upheavals and traumas of the times.