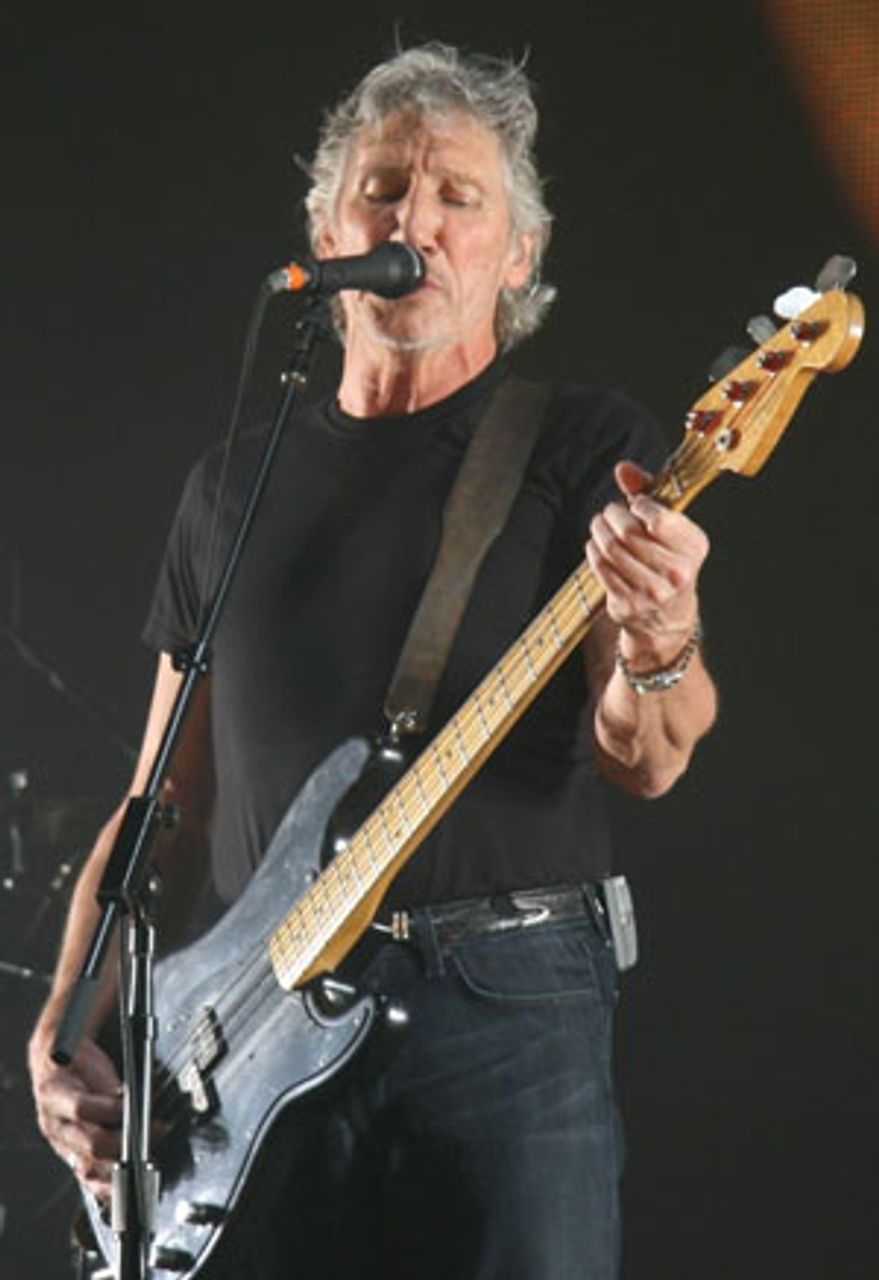

Roger Waters Photo: Eddie Berman

Roger Waters Photo: Eddie BermanIn 1979, the progressive rock band Pink Floyd released its 11th studio album, entitled The Wall, which was to be accompanied by possibly the most ambitious live show in rock history as well as a film, released in 1982 and directed by Alan Parker. The live show centered on the building of a 40-foot-high wall separating the audience from the band. Huge animations were projected onto the wall, which effectively became a giant screen, while giant inflatable monsters stalked the stage and the band played variously from behind, in front of and on top of the wall.

Roger Waters, the band’s bassist and lead songwriter, committed this year to taking the show back on stage for the first time since an enormous 1990 concert in the no-man's land at the site of the Berlin Wall that had until then divided Berlin between East and West. While Waters is utilizing the most modern projection and lighting technology, computer graphics and stage effects, the major change to the show is the integration of new political commentary and the accentuation of previous statements in the music.

Over the last four decades, both under the Pink Floyd name and under his own, Waters has been releasing music that is powerfully opposed to religion, imperialism and capitalism. His last solo rock album, Amused to Death (1992), was explicit and unreserved in its criticism of contemporary society—in ambitious songs like “What God Wants,” “The Bravery of Being out of Range” (about the Gulf War) and “Perfect Sense,” in which a massive audience bellows the “global anthem:” “It all makes perfect sense expressed in dollars and cents, pounds shillings and pence!”

In 2005, Waters released two singles over the Internet that made clear his opposition to the Iraq War and the Bush administration (“To Kill The Child”) and to the demonization of the people of the Middle East (“Leaving Beirut”).

His new tour furthers these positions. Apache helicopters roar toward the audience, Boeing bombers drop crosses, Stars of David and dollars signs, faces of dead soldiers and civilians linger on the screen and a giant projected camera “spies” on the audience. Waters rouses the audience with a resounding rendition of “Bring The Boys Back Home,” in which he dramatically projects a quotation from Dwight D. Eisenhower across The Wall: “Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired, signifies, in the final sense, a theft, from those who hunger, and are not fed, those who are cold, and not clothed.”

Waters’ music and his Wall show in particular represent a unique achievement for the rock genre. The development of rock as an artistic form has been contradictory. While rock was gradually induced to take itself more seriously by the late 1960s as the youth became more assertive and politically involved, the genre mostly absorbed the mindset that was politically expressed by the New Left. Lyrics, while no longer dwelling in the clichés of earlier love songs, were often nonsensical and at most reflected the banalities of drug use, Eastern religions and a pretentious ambiguity toward all questions that raised social (especially class) and not merely individual questions.

New experimentation in rock during the late 1960s matured into progressive rock at the beginning of the 1970s. Pink Floyd was originally a “psychedelic” band with typical nonsense lyrics and themes, becoming only gradually a band known for its deep and challenging concept albums. While progressive rock made important advances in the 1970s, it suffered greatly from the inability of progressive rock bands to concentrate on real social problems and concerns, leading to the subgenre’s association with fantastic, vacuous themes and pointless instrumentals. By the late 1970s, progressive rock had become discredited and its stylistic opposite, punk, captured the imagination of rock listeners for a time. The Wall’s success at the end of the 1970s was surprising during the period of progressive rock’s decline. Progressive rock never recovered as a dominant form of rock music, and many of its bands returned to more radio-friendly music in the 1980s, before largely disappearing from the public consciousness in the 1990s.

It is clear that Waters’ achievements should be welcomed when seen in the context of rock history, which has a tragically dismal record with political and social commentary. There are however, areas in which The Wall reflects confusion and vacillation on the part of Waters that are characteristic of the petty-bourgeois “far left” in the United States, where he now lives. Waters, who goes as far as putting George W. Bush’s picture next to Mao’s, Stalin’s and Hitler’s during The Wall concert, air-dropped leaflets lauding Barack Obama during his 2008 presidential campaign. Waters has been outspoken in his criticism of Bush, Tony Blair and past presidents and prime ministers in interviews, on albums and during his concerts in the past, but he now refrains from addressing his stance toward Obama, who has pursued a path identical to Bush.

Waters is unwilling to draw conclusions from his criticisms of capitalism and the government. He does not want to lean too far in any one direction. Waters carefully prepares the concert’s projections to give equal consideration to American soldiers who have died in the wars and to civilian victims. Along with the cross, Star of David and the dollar sign, he shows B-52s dropping crescent moons and hammer and sickles! This can only confuse the audience. What exactly is to replace the chilling slavery and mayhem that Waters so boldly presents to the audience as their reality? What action can we take? Certainly The Wall’s unaltered conclusion, that “the bleeding hearts and the artists” in their “ones” and “twos” are burdened with task of correcting the world, is inadequate and irresponsible to suggest. Why bring audiences together and rip part of the façade off capitalism only to tell the audience that there is nothing for them to do—that, as the New Left used to say, “all ideologies are wrong” and what we need is common decency?

The Wall remains, however, a positive application of rock music to the exposure of the barbarism and hatred that weigh down on working people all over the world. It remains for rock musicians and all artists to draw principled conclusions from the suffering and the inequities of modern life and use their creative gifts to enrich their audience’s vision of the future and give them the confidence to pursue the necessary struggles.

Terrence McGovern

6 October 2010