This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Scientists confirm hole in ozone

NASA image of ozone hole at its largest

NASA image of ozone hole at its largestrecorded size in 2006

Measurements taken by the Nimbus 7 satellite and confirmed this week in 1985 revealed the growth of a hole in the atmosphere’s protective strata of gas known as the ozone layer above Antarctica. A number of scientists linked the depletion to human pollution.

For several years scientists had noticed what appeared to be a hole in the ozone layer that emerged each October, and that appeared to grow larger with each successive year. Dr. Donald F. Heath of the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland said November 6, 1985, that analysis of the satellite data confirmed the hole’s existence and indicated that it was growing more rapidly than previously thought.

Although the link between human pollution and the hole in the ozone could not be fully established, since 1974 it had been predicted that certain substances would deplete the ozone layer, among these fluorocarbons, nitrous oxide, bromine compounds, and methane.

As early as 1980, the US National Academy of Scientists had warned that even a moderate reduction in the size of the ozone layer would likely drastically increase cases of melanoma, weaken production of certain crops, and destroy the larvae of some marine species.

50 years ago: France assassinates Cameroonian revolutionary in Geneva

Félix Moumié

Félix MoumiéOn November 3, 1960, Félix-Roland Moumié, a nationalist revolutionary from Cameroon, was assassinated on a trip to Switzerland by French secret service agents. Moumié, 35, was administered a fatal dose of thallium in Geneva.

Moumié was a leader of the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (UPC), which had been created in 1948 among Cameroonian trade unionists. It was outlawed by the French colony in 1955. This precipitated guerilla war against the French colonizers, the minority white settlers and other pro-French elements that lasted until 1970. Moumié’s predecessor as leader of the UPC, Ruben Um Nyobé, was gunned down by French commandos in 1958 near his native village.

Moumié’s assassination came only weeks after Cameroon was granted formal independence under the French puppet government of Ahmadou Ahidjo, and as French Cameroun and British Cameroon made preparations for unification.

Though its guilt was never seriously in doubt, France long denied responsibility for the killing of Moumié. Much later a number of agents and high-ranking officials admitted their involvement or were otherwise implicated in the assassination, among them two former prime ministers, Michelle Debré and Pierre Mesmer, and Jacques Forccart, President Charles De Gaulle’s Chief of Staff for Africa. Messmer and Forccart both justified the killing, calling Moumié a communist. “Je ne crois pas que cela ait été une erreur,”—I don’t believe it was an error—Forccart declared in a 1995 interview. No one has ever been held to account for the crime.

France’s dirty war in Cameroon was overshadowed by its humiliating defeat in Vietnam (1946-1954) and its failure to retain Algeria after a brutal war against the Arab population (1954-1962), but tens of thousands were also killed in the French effort to maintain its interests in the west African nation, with some estimates going as high as 300,000 to 400,000 dead.

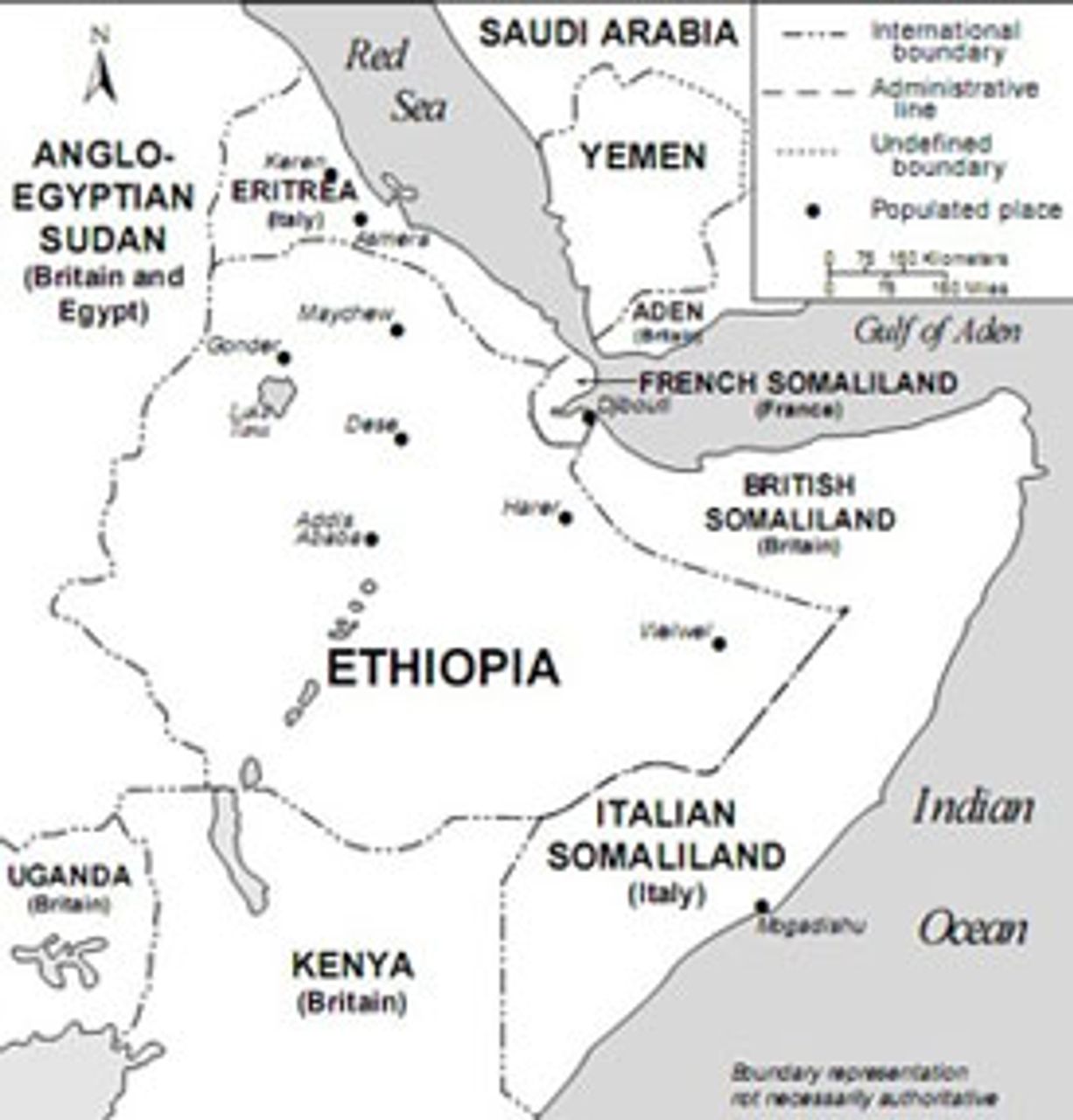

75 years ago: The rape of Ethiopia

Horn of Africa before Italian invasion

Horn of Africa before Italian invasionIn the second major advance of the Italian military in Ethiopia, 120,000 of the country’s soldiers began a march toward Mek’ele this week in 1935 with the aim of once again capturing the city for Italy. Italian troops had previously occupied Mek’ele during the first Italo-Abyssinian War (1895-1896).

Under the leadership of General Emilio De Bono, the Italian army marched across 25 miles of Ethiopian territory, seizing control of the towns of Hawzen and Enda Abbamas as they made their way. The army built roads for trucks and other military vehicles as they traveled to compensate for the lack of modern infrastructure in the Ethiopian terrain. They met with little opposition from the outmatched Ethiopian forces. By the week’s end, Mek’ele fell to Italy.

As the Italian army penetrated further into his country, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie delivered a radio address broadcast in the United States in a desperate attempt to gain the support of the US and other non-member states in supporting the League of Nations’ sanctions against Italy. “Ethiopia does not desire to involve other peoples and other nations in her distress,” said Selassie, “But now the time has come—at Geneva the hour for collective action against the aggressor has been solemnly marked by nations in conference assembled. Sanctions will be formally applied within a few days in a sincere attempt to kill the dogs of war.”

Ultimately, the major imperialist powers forced no sanctions on Italy capable of bringing an end to Mussolini’s war, and not all member countries observed the sanctions that were put in place. Britain and France, in particular, refused to take a strong stand against Italy as they still hoped to gain Mussolini as an ally against the threat posed by Adolf Hitler in Germany.

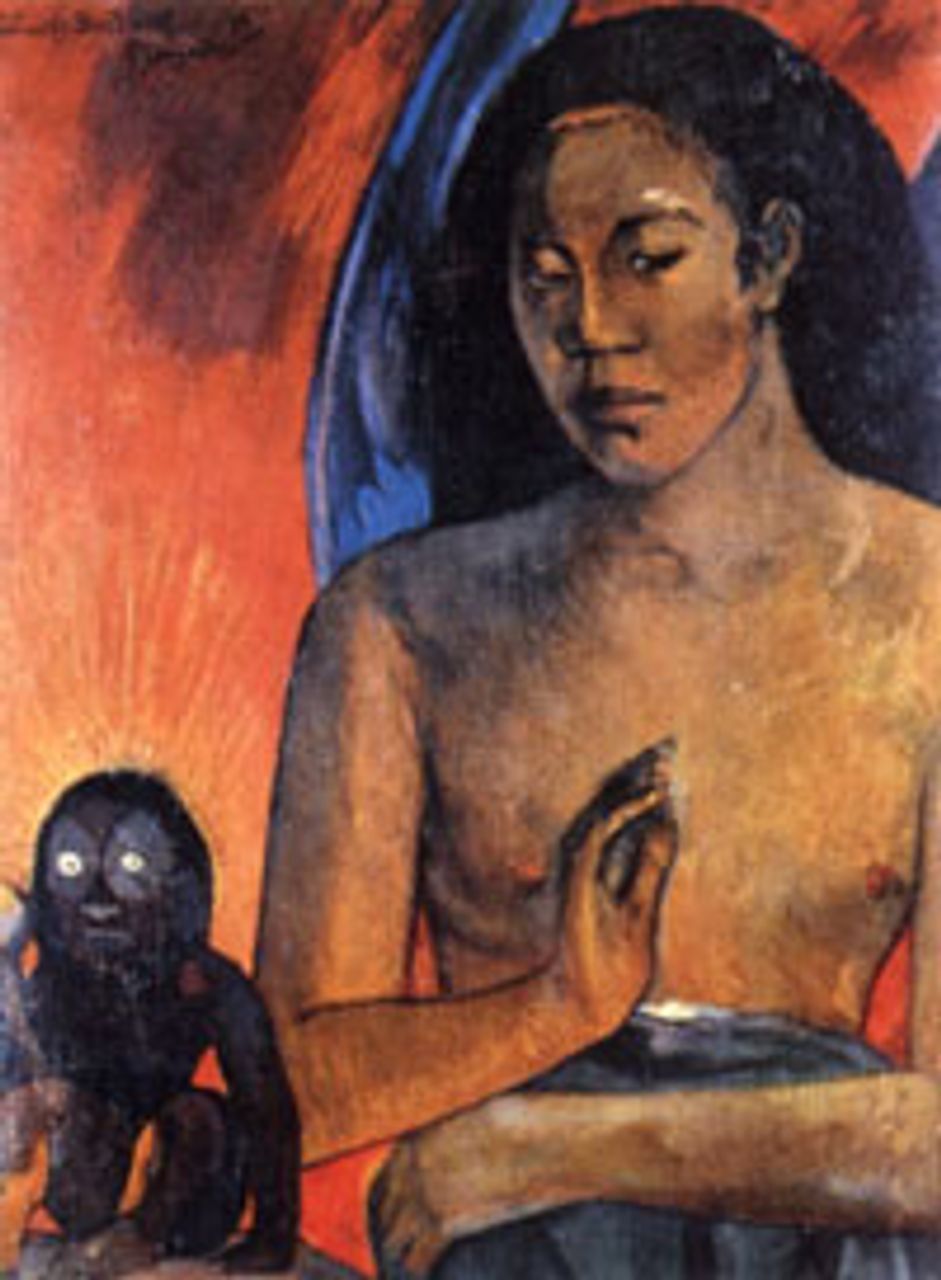

100 years ago: British critics attack post-impressionist art exhibition

Poemes Barbares, Gauguin, 1896

Poemes Barbares, Gauguin, 1896A major showing of works by Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Matisse, premiering November 5 1910—Guy Fawkes Day—shocked British art critics and stirred up a long-lasting debate about what quickly came to be called “post-impressionist” art.

According to the art historian Rachel Teukolsky, “the paintings’ styles looked so unlike the realist canvases to which the British public was accustomed, that some reviewers accused the artists of attempting literally to destroy the Western visual canon.” A number of critics associated the paintings with French revolutionary political traditions. “[I]n France a reform movement always has its section who are for the barricades, the guillotine, and the Anarchist’s bomb,” lamented a review for the Spectator.

The critical furor, however, drew enormous interest in the showing, which was held in London’s fashionable Grafton Galleries, and soon helped to establish post-impressionism itself as an established form of art highly sought after by collectors.

During the exhibition, event organizer Roger Fry wrote that the post-impressionists “are in revolt against the photographic realism of the nineteenth century…[they are] cutting away the merely representative element in art to establish…the fundamental laws of expressive form in its barest, most abstract elements.”