This is the sixth in a series of articles on the recent Berlin International Film Festival, February 11-21. Part one was posted on February 24, part two appeared February 26, part three March 3, part four March 6 and part five March 11.

The documentary, Fritz Bauer—Tod auf Raten (Fritz Bauer—Death by Instalments), directed by Ilona Ziok, celebrates the German jurist and prosecutor Fritz Bauer (1903-1968), who now—unjustly—is almost forgotten. His name is missing, for example, from Manfred Görtemaker’s History of the Federal Republic.

Fritz Bauer was a Jew and a Social Democrat, who endured time in concentration camps and in exile under the Nazi regime. From 1956 Bauer was the Hesse state attorney general in Frankfurt and one of the few prominent lawyers who had not had a career in the Third Reich.

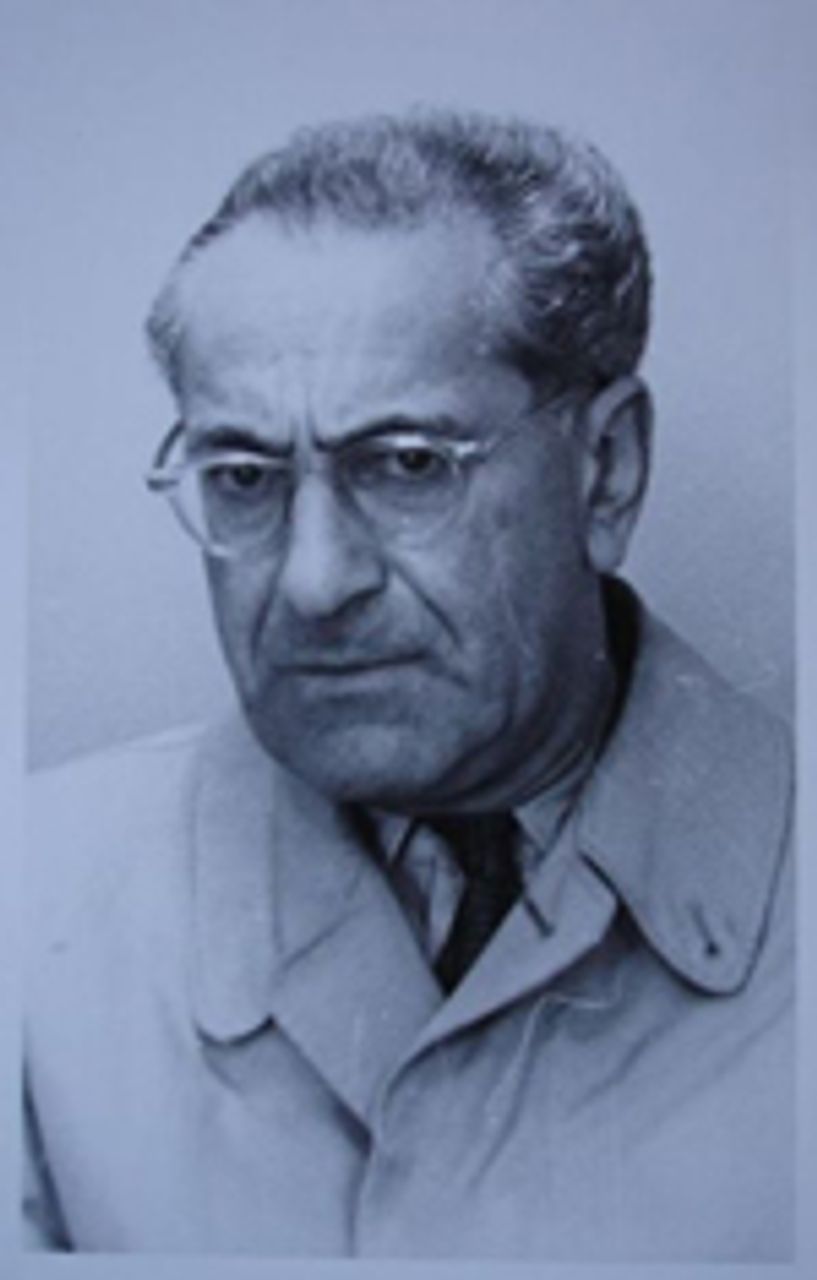

Fritz Bauer

Fritz BauerAfter the Second World War, most of the former fascist officials, including those in the judiciary, showed no sense of guilt about the Nazi crimes, claiming they had only been following orders and serving the state, i.e., Hitler. In the new West Germany, former SS officers stubbornly, and in many cases, successfully, insisted on reinstatement or the payment of their pensions.

For his part, Bauer fought for the general right to resist the crimes of the state. For him, it was not only the military opposition of July 20, 1944, (when elements in the army and intelligence attempted and failed to assassinate Hitler) that was laudable, but also the Communist Party-led resistance. Bauer instigated the famous Frankfurt Auschwitz trial (1963-1965), and was preparing a lawsuit against the legal perpetrators of euthanasia, when he died in 1968 under mysterious circumstances.

With the help of historical archive material, including a meeting of lawyers and students in 1964, and interviews with eyewitnesses, the film succeeds in presenting Bauer as an honest and principled opponent of the Nazi judicial swamp that dominated West Germany in the 1950s and 1960s. This filthy crowd displayed brazen self-assurance in the face of any attempt to hold them accountable for their crimes under the Hitler regime.

We learn that Bauer secretly supplied Israeli intelligence with information that led to the arrest of Nazi criminal Adolf Eichmann in 1961. Bauer was certain that an official extradition request would have meant Eichmann being immediately alerted by officials from the relevant German authorities.

The film shows how former Nazi judges exhibited an unparalleled cynicism toward the victims of the Hitler regime, their former enemies.

From Fritz Bauer—Death by Instalments

From Fritz Bauer—Death by InstalmentsExisting criminal law (which dated in part from the time of the former kaiser’s regime) was not designed to deal with mass murder. So Nazi murderers got off with minor penalties.

The film draws attention to the case of the influential jurist Eduard Dreher, who was the leading prosecutor of the Special Court in Innsbruck during the Nazi era. In post-war West Germany, he drafted a bill—which in combination with the statute of limitations already adopted—made the punishment of Nazi criminals virtually impossible in the future. Dreher—known today for a standard legal work, his commentary on the Penal Code—drew up the law, the film suggests, so cleverly that the Bundestag (German parliament) was deceived. It was unanimously adopted, including with the votes of Willy Brandt, later the Social Democratic Party (SPD) chancellor, and then SPD leader Herbert Wehner.

Ingo Müller, author of Furchtbare Juristen (Horrible Jurists, 1987), points out that before the bill was introduced in the Bundestag, it passed before several panels of experts, which leads one to conclude that there was a tacit consensus in ruling circles about the need to put an end to investigations into and prosecutions of those responsible for the Nazi horrors.

Müller’s argument would also help explain why the Bundestag failed to adopt laws condemning mass murder, and why, in 1960, the ability to punish many of the crimes committed in the Nazi era was allowed to expire under the statute of limitations. Fritz Bauer commented critically about this, declaring it was no surprise that the courts and prosecutors concluded that, “according to the legislative and executive branches, the legal process of dealing with the past was closed.”

From Fritz Bauer—Death by Instalments

From Fritz Bauer—Death by InstalmentsThe main merit of the film is its examination and reminder of the Nazi past. Incidentally, Ziok’s documentary also features a young Christian Democratic politician named Helmut Kohl, who in 1962 took up the cudgels against Bauer, declaring that it was not possible to form an objective opinion concerning Nazism! This was only 17 years after the fall of the Third Reich. In 1982, of course, the right-wing Kohl became German chancellor.

Ernst Achenbach (1909-91), the Free Democratic Party (FDP) parliamentary deputy and former Nazi, like many others in that party, is also mentioned.

One is continually reminded by Fritz Bauer—Death by Instalments of the outrageous fact that virtually the entire Nazi judiciary found employment in the legal apparatus of West Germany, including the first president of the Federal Court, also a former judge under Hitler.

The film expresses honest indignation, and certainly contributes to forming a critical attitude toward the machinery of the modern German state. However, the documentary is rather limited when it comes to present-day realities. Two of those interviewed in the film express their conviction that the conditions existing in Bauer’s time as prosecutor are no longer possible today. Of course, for obvious reasons of time and age, there are no former Nazis currently sitting in the Bundestag. However, the examination of the past “legal errors,” as Ingo Müller ironically describes them, would be instructive.

Laws are passed today that play directly into the hands of right-wing forces. In this regard, it should be pointed out that—despite the collapse and discrediting of the Third Reich—the state’s authoritarian approach in protecting the interests of the wealthy elite has certainly persisted.

A degree of social polarisation has now emerged representing a fundamental break with the post-war “social partnership” that predominated in Germany. Tax breaks for the rich and the adoption of the Hartz IV anti-welfare “reforms,” introduced by the former SPD-Green Party government, followed by the government’s massive bank bail-out, are symptomatic of this process. Pouring oil on the flames, German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle (FDP) has uttered a series of demagogic outbursts against welfare recipients.

During the Nazi era, Eduard Dreher, as a representative of class justice, demanded the harshest punishment for trivial crimes. At his insistence, an ordinary gardener was sentenced to death for the crime of stealing some food and using a bicycle without authorization.

The unanimous adoption of the aforementioned Dreher law in 1968 dealt Fritz Bauer a severe blow. The passage of emergency laws by the grand coalition of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and SPD in the same year, at a time of political unrest and growing economic crisis, giving the state the right to limit basic democratic rights, left Bauer—a Social Democrat—shocked and helpless. All the more because it was his party helping to give an impetus to ultra-right, anti-democratic forces, against whom he had stubbornly fought for so long. Bauer died only a few weeks later.

The author also recommends:

Forty years since the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial: Part 3—Juridical cover-up of Nazi crimes

[29 April 2004]

To be continued