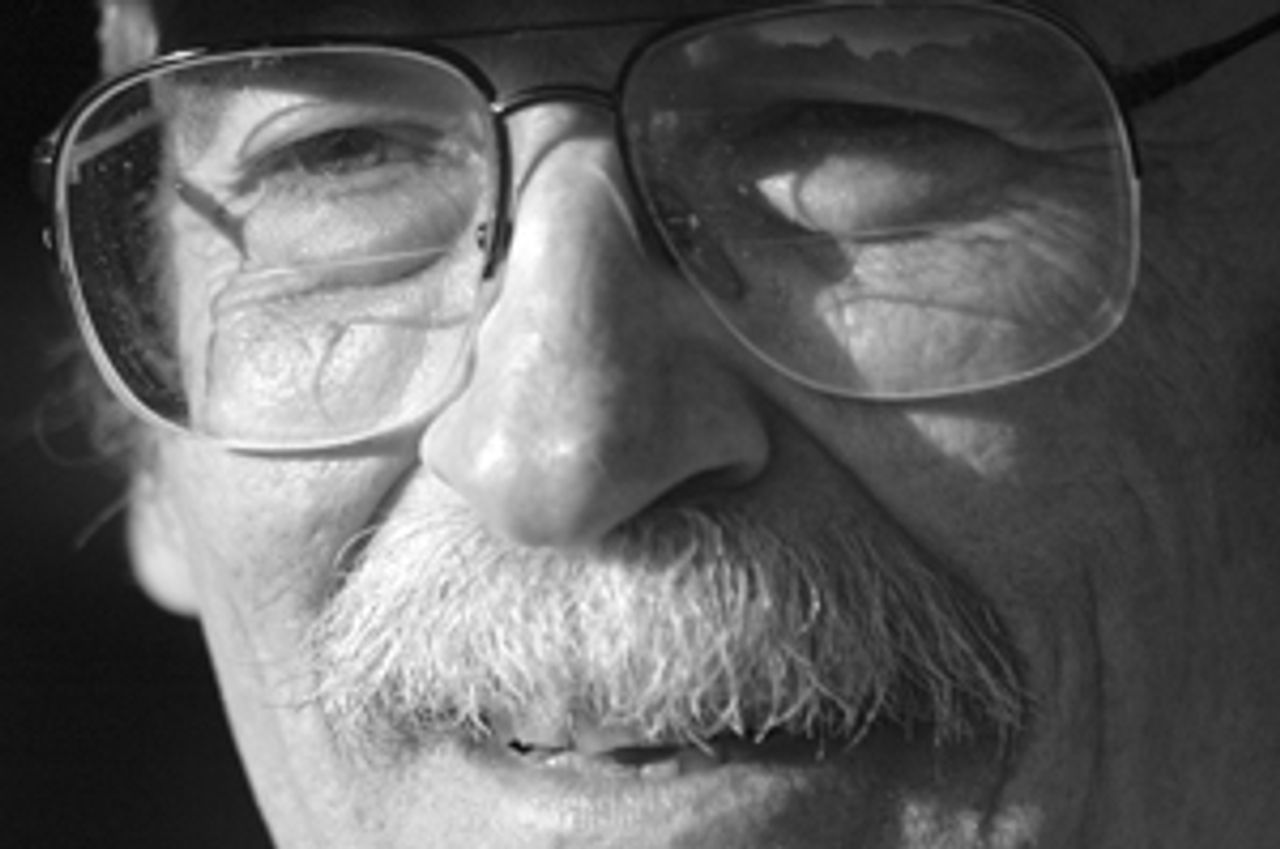

Richard Brenneman being interviewed for the Marina Zenovich documentary, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired

Richard Brenneman being interviewed for the Marina Zenovich documentary, Roman Polanski: Wanted and DesiredSwiss authorities announced July 12 that 76-year-old filmmaker Roman Polanski would not be extradited to the US. Polanski was arrested September 26, 2009 on his arrival in Zurich to attend a film festival. He remained under house arrest at his chalet in Gstaad until the Swiss justice ministry rendered its recent decision.

Roman Polanski

Roman PolanskiThe effort by the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office, assisted by the Obama administration’s Justice Department, to extradite Polanski in relation to charges of having sex with a teenage girl dating to the late 1970s, was a vindictive and politically motivated act.

An unsavory alliance of extreme right-wingers, feminists and liberal media pundits came together over the Polanski issue, demanding that “justice be done” once and for all in the case of this “rapist” and “pedophile.” Erstwhile “left” elements paid no attention to the facts of the case, including the systematic violation of Polanski’s rights by the judge in the case in 1977-78, or its social and political implications, so blinded are they by the prejudices of identity politics.

As we noted earlier in July, this sordid coalition “uses inflammatory, fake populist arguments as a means of whipping up the most backward layers of the American population with hot-button appeals to the ‘protection of children against predators.’ The targets of this lynch mob are ‘Hollywood types,’ artists, intellectuals and non-conformists of every variety. The anti-Polanski effort has undertones of xenophobia and anti-Semitism, along with old-fashioned American Puritanism.”

Richard Brenneman

Richard BrennemanRichard Brenneman is an author and veteran journalist, who covered the Polanski case for the Santa Monica [California] Evening Outlook. As the newspaper’s court reporter, he had a unique vantage point on the events and an unusual relationship with Judge Laurence J. Rittenband. Brenneman figures prominently in the 2008 documentary, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, directed by Marina Zenovich. He has written numerous recent articles on the case.

Brenneman was kind enough to consent to a telephone interview. He spoke to us from his home in Berkeley, California.

David Walsh: Can you tell me how you got involved in coverage of the Roman Polanski case?

Richard Brenneman: I was hired by the Santa Monica Evening Outlook, a newspaper that no longer exists, to cover the courts and do special projects—investigative work, as it were. And the first case I covered was a murder case with connections to Chicago organized crime apparently. It was in the courtroom of a judge named Laurence Rittenband.

Rittenband was the senior judge on the Santa Monica court. When the Polanski case came to Santa Monica, he grabbed the case. Since I’d been covering trials in his courtroom for the previous several months, Rittenband basically appointed me the liaison to the out-of-town press that poured in for the case.

DW: What was your impression of the press corps? Were there especially disreputable elements?

RB: One tabloid, for example, offered me $25,000—a considerable sum of money in 1977—if I would give them the inside details on the young woman involved in the case, and help them set up an ambush photo of her.

DW: Did you have any encounters with Polanski himself?

RB: Not until many years later. Twenty years later, I spoke to him briefly, when I was thinking of writing a book about the case. He was very calm and very reasonable. We didn’t discuss the details of the case. We discussed more about how intense media coverage and sensationalism can influence the judicial process.

In 1977, from a distance, my initial sense of Polanski was of someone stunned by what had happened.

It was a perfect Hollywood case. You had someone who was a controversial figure, he had made some brilliant films, including Chinatown—which as the case went on I came to see as really a cinematic foreshadowing of what happened to him. He was Jewish, he was short, he was the victim of the most brutal mass murder cult California has seen, he was someone who was associated with all manner of rumors, especially once the case began.

DW: You can’t help but think that here was someone who was a prime target for scapegoating and the media frenzy.

RB: The fact that the case was grabbed by a judge such as Rittenband who was obsessed with celebrity, and who considered himself something of a celebrity, had the most profound impact on what came about.

The conduct of the district attorney’s office, to my mind, was exemplary. The individual who handled the case, Roger Gunson, is an extremely honest individual. The district attorney at the time, John Van de Kamp, was a reasonable person himself. Their interest was in seeing a resolution of the case. They wanted a conviction on the record, but when the victim let it be known that she would not under any circumstances provide any testimony in the case, they were faced with the necessity of arriving at a plea bargain.

Douglas Dalton, Polanski’s lawyer, had a reputation for being a superb negotiator, and his talent lay there. He was not a flamboyant attorney at all.

DW: One of the most fascinating aspects you deal with in your articles is the history and character of Judge Rittenband, a prominent figure in this whole affair.

RB: Judge Rittenband was a most impressive human being, but the man who was most impressed with Judge Rittenband was Judge Rittenband. In some ways, he was a classical figure. Like Polanski, he was short, he was Jewish, he was brilliant and he knew he was brilliant. He was fascinated with the darker side of life.

They were both celebrities. Rittenband was a celebrity at the Hillcrest Country Club, where he mingled with some of the wealthiest, most powerful and influential people in the country.

Polanski moved in exalted circles. They had some acquaintances in common, because some of the film industry people hung out at the club, as did the judge.

DW: What was the significance of the Hillcrest Country Club at the time?

RB: Back in the 1920s, the Los Angeles Country Club, the gathering place of the elite, would not take actors or Jews as members. Members of the wealthy Jewish population in Los Angeles decided to form their own country club, and Hillcrest was the result. Hillcrest was, and is, a gathering place of the elite. Memberships are inheritable, and legal battles have been fought over it. It is a place of privilege and power, where a lot of dealing goes on, just as at the L.A. Country Club.

Rittenband held court there. The club’s main dining room was for men only. When you walked into center of the dining room, there was a pillar. The judge’s table was at the pillar, in what I call the gunfighter’s seat. With his back to the pillar, he saw everyone who came into the room, everyone saw him. Everyone would walk by and pay tribute to him as they walked in. He had the power seat in the power institution.

His best friend, Sidney Korshak, was an attorney who never bothered to get his legal ticket in California, and who was identified by both the US and the California attorney general as the principal link between organized crime, business and labor politics in the US.

Korshak, from Chicago, had been sent out by the Capone organization as their representative in Los Angeles to the film industry. His closest ally in the industry was Lew Wasserman, the head of MCA Universal, the largest film producer and the largest producer of television in the world at the time. Wasserman had constant contact with Korshak. Wasserman was also Ronald Reagan’s agent back in his show business days. Both Reagan and Korshak were groomsmen at Frank Sinatra’s wedding.

DW: When you mention all these connections, it makes you wonder about the forces that wanted to see Polanski punished.

RB: The judge was not vindictive toward Polanski originally. If anything, he was somewhat sympathetic, or even cynical. His initial reaction, on hearing the details of the case, was ‘Oh, was this a mother-daughter hooker team?’

At the time, the judge was dating a woman who was 19 when they first met, he was now 70.

DW: According to your articles, Rittenband was complaining that he was getting phone calls pressuring him to be tougher on Polanski. Who was he getting phone calls from?

RB: The wives of his friends from Hillcrest. The whole thing spun out of control as the result of something I witnessed while waiting for breaks on the Polanski case. It was a rape case involving a 19-year-old schizophrenic girl. The woman was examined on the stand by the prosecutor, and when it came time for the defense to examine her, she went catatonic. She threw her arms across her chest and refused to respond.

Judge Rittenband asked her to testify, explaining that the law says it’s a fundamental right of the defendant to cross-examine any witnesses against him.

None of that was reaching her. After a couple of times of gentle prompting, Rittenband railed at her from the bench—it stunned everyone in the courtroom. And when she still refused to testify, he had his bailiff arrest her on contempt, and handcuff her, take her out of the courtroom. She was hauled off to jail. When she came back the next day, her face was covered with angry bruises, also stitches, I believe. On the jail bus, a bunch of black women had tried to talk to her, and when she didn’t answer, they took it as a sign of racial prejudice, and laid into her.

When she came back into the courtroom, everyone was stunned. She did manage to make it through her testimony. I wrote stories about it, both when she was arrested and when she came back with her injuries. This was precisely at the moment that the attorneys were hammering out the details of the plea agreement in the Polanski case. The agreement was reached on the same day that my story about the girl’s beating came out.

We were an afternoon paper, and so the paper didn’t arrive at the homes of Rittenband’s Hillcrest friends until after the decision had been reached. He got home after reaching the deal with Polanski, and he was deluged with phone calls. It was then that the judge called me into chambers, the next day, after getting all these calls, and he looked at me and said, ‘Dick, what the hell do I do with Polanski?’

He was asking me, as a reporter, basically what decision he could make that would play best in the press.

DW: This was not a rhetorical question.

RB: No, he called me into chambers, that was the clear indication of his intent. He wanted advice.

DW: How did you respond at that moment?

RB: I just remember leaning back and throwing my hands up, and saying, ‘Judge, that’s your decision, there’s nothing I can say.’ I was absolutely astounded. First of all, if he’d been smart, he could have conducted a roundabout conversation and gotten the information he’d wanted in the course of it. Just like any good interviewer. And I realized that if I told him something, he’d do it. It was the most stunning single encounter that I’ve ever had as a journalist with a figure in power.

His concern was not at all about justice, his sole concern was in saving face.

DW: The judge’s decision later to send Polanski to Chino State Prison for 90 days for the diagnostic analysis …

RB: That was illegal. A psychiatric diagnosis cannot be imposed as a sentence. In any case, there was no reason to send him to Chino. Two psychiatrists and the county’s most skilled probation officer all reached the conclusion that there was nothing about Polanski that mandated prison time whatsoever. They concluded that he was not a mentally disordered sex offender.

The only reason Rittenband sent him to Chino was so he could say, ‘I sent the son of a bitch to prison.’ It was absolutely blatant.

In any event, Polanski was released in January 1978, after 42 days. And there were more phone calls. What Rittenband is hearing from his pals at Hillcrest, or their wives, is, ‘You’ve got to send this guy to prison, 42 days is a farce.’

The judge at that point decided, ‘Well, it’s a 90-day diagnostic, so I’ll send him back for another 48 days.’ The problem is, it’s very questionable whether a judge can send anyone to state prison for 48 days. Anything less than a year is handled in the county jail. But Rittenband wanted prison, and the only reason Rittenband wanted prison was self-serving, his own reputation. Justice had nothing do with it.

DW: When did he decide to renege on the plea bargain?

RB: What I think happened is that after Polanski got out … and I would defy anyone to spend 42 days in Chino and think it was not punishment. Regardless of that, the 90 day figure was out there, which is the maximum under law for this process. Forty-two days was not an unusual period of time for one of these evaluations.

The judge knew that. My perception was that the figure of 90 days got taken up by his friends, and they all presumed that Polanski would be doing three months in prison. And when it turned out to be less than a month and a half, this is informed speculation, the judge was confronted with ‘90 days isn’t much, and you didn’t even give him that!’

So Rittenband at that point completely lost it. You have to remember that this judge was a raging egomaniac. He had his bailiff keep leather-bound volumes of all the clippings about his cases, which he would have the bailiff show to reporters who asked about him. I have never seen that.

Here was the judge for the first time getting bad press in his career. He had lost high-profile cases in the past, Elvis Presley, Cary Grant, Marlon Brando, on and on. Here he was getting the negative feedback and he was desperate to save face.

What I think happened, and the reason Polanski fled, was this: Rittenband played tennis every day at the Hillcrest. One day after tennis, in mid-December 1977, Rittenband went into the shower room and producer Howard Koch was there and he overheard Rittenband tell someone ‘I’m going to give him the maximum.’ My sense is that Koch misunderstood what he meant. I think the judge meant to say, I’ll give him all the 90 days, the maximum for the diagnostic process. Koch interpreted it as the maximum for the crime pled to, at least a couple of years in state prison, if not more.

Even Roger Gunson, in the documentary Wanted and Desired, acknowledges that he couldn’t be sure what the judge would do. So no one knew what the judge would do, and Polanski, having fulfilled every aspect of the plea agreement—including having done the prison time specified in the plea bargain—took it upon himself to flee, and, honestly, had I been in the same situation, with the resources that Polanski had, I probably would have left the country too. Because the judge was crazy.

DW: What was your reaction when Polanski was arrested in Switzerland last September?

RB: Let’s go back first to when I found out that the judge died. He died in 1993, but I didn’t find out about it until three years later. The moment that I found out, I sat down and wrote out an affidavit, and sent it to Doug Dalton, Polanski's attorney, telling him that the judge had called me into chambers and that I considered this improper conduct, and that if it ever became necessary, I would be glad to testify.

I wrote the letter then because I had an agreement with the judge that anything we discussed in chambers I would not divulge. The judge would give me background, would explain points of law to me, because I had never covered the courts before—so he was a source. When I learned the judge had died, the agreement was terminated, and since I had facts that might determine the outcome of the case, I was morally obligated to come forward and say what I knew.

So when Polanski was arrested, my first response was, ‘Oh, shit, this is all going to be coming up again.’ The fact that he was arrested in Switzerland surprised me, because I knew he had been visiting there for years. When the arrest broke, my immediate assumption was that I might find myself in play in this again, as a witness this time.

I thought: why the hell is the L.A. district attorney bringing this up again? My conclusion was that they had been so embarrassed by the documentary, Wanted and Desired, in which I told my story and which raised the case in a manner in which I was glad to see it raised.

Why the hell don’t they just leave this alone?

I think this has to do with the political ambitions of the Los Angeles district attorney, Steve Cooley, as well. Here he is, wanting to become state attorney general, and here he can …

A big difference in context between the time of the original case and the present day is that the Polanski case was kind of the final act in the death of the 1960s. There was a much different attitude toward sex in those days. There was no HIV. In the years since there has been this whole hysteria about ‘sex abuse cults’ of children; we’ve become extremely sensitized to child sexuality and exploitation, never mind that the biggest culprits in this are the media anyway.

When Polanski was arrested again, it was a perfect vehicle for pushing a whole bunch of politically sensitive hot buttons with the Republican base, sexual abuse of children, European decadence, Hollywood decadence, society corruption. It was a perfect way for the DA to get his name in the press in ways that would give him favorable coverage.

DW: One of the nails in the coffin of the extradition process was the refusal of the California authorities to provide the Swiss with the transcript of testimony Roger Gunson provided this past winter.

RB: Everyone knows the content of his testimony, he speaks about it in the documentary. He would have made a case for judicial misconduct. The district attorney’s office doesn’t want it officially known that it broke an agreement into which it had entered with Polanski. But the superior court system has no interest in seeing those transcripts either. They didn’t want the revelation that one of their most esteemed judges, one of their highest profile judges, had been corrupt.

A lot of people are happy that it played out this way, without the facts about the misconduct and corruption coming out.

I have a larger question.

At the time the case happened in 1977, I didn’t realize who Sid Korshak was. I had had lunch with the man Rittenband introduced as ‘My friend Sidney’ at the Hillcrest. But I didn’t know who Sidney Korshak was. I simply noticed that when the three of us were having lunch at the judge’s table, that all eyes in the room at one point or another were on us. I had the definite feeling that I was part of something significant and that I hadn’t the faintest notion what it was.

In addition to his celebrity trials, Judge Rittenband did all the law and motion work for the Santa Monica courthouse. That is, when a case before any of the judges in the courthouse needed a legal reading on it, or if there was a motion to be considered, Rittenband was the one who made the decision, and those decisions can often effectively determine the outcome of a case, one way or another. If a judge decides a case has been brought improperly, or whatever, the case is thrown out. Or a ruling could buttress a case.

The judge was in a position of tremendous power. Every Friday morning he held law and motion calendar in his room. Typically, he would start out with a pile beside him two feet high, and people would come in and argue their motions.

Bear in mind his association with Korshak, and Korshak’s position of power, which was phenomenal. Rittenband with a single decision could torpedo or buttress a case. This raises a legitimate question, was he the mob’s fixer? I don’t know the answer.

The Santa Monica courthouse covered all of Westwood, Beverly Hills, Bel Air, Brentwood, Malibu, Century City, where the majority of the town’s well-off lawyers had or still have their offices. No judge was in a position of greater power in the nation’s largest substate judicial system. Who knows what the judge was doing? I don’t, but I have every reason to suspect that not everything was on the up and up.

If we had a strong press corps in this country, and since the time of the Polanski case, the press corps has been gutted, reporters would go into and take a look at the judge’s decisions. Is there someone else today who’s fulfilling that same role? I don’t know. We won’t know, because the nation’s press corps has been tamed.