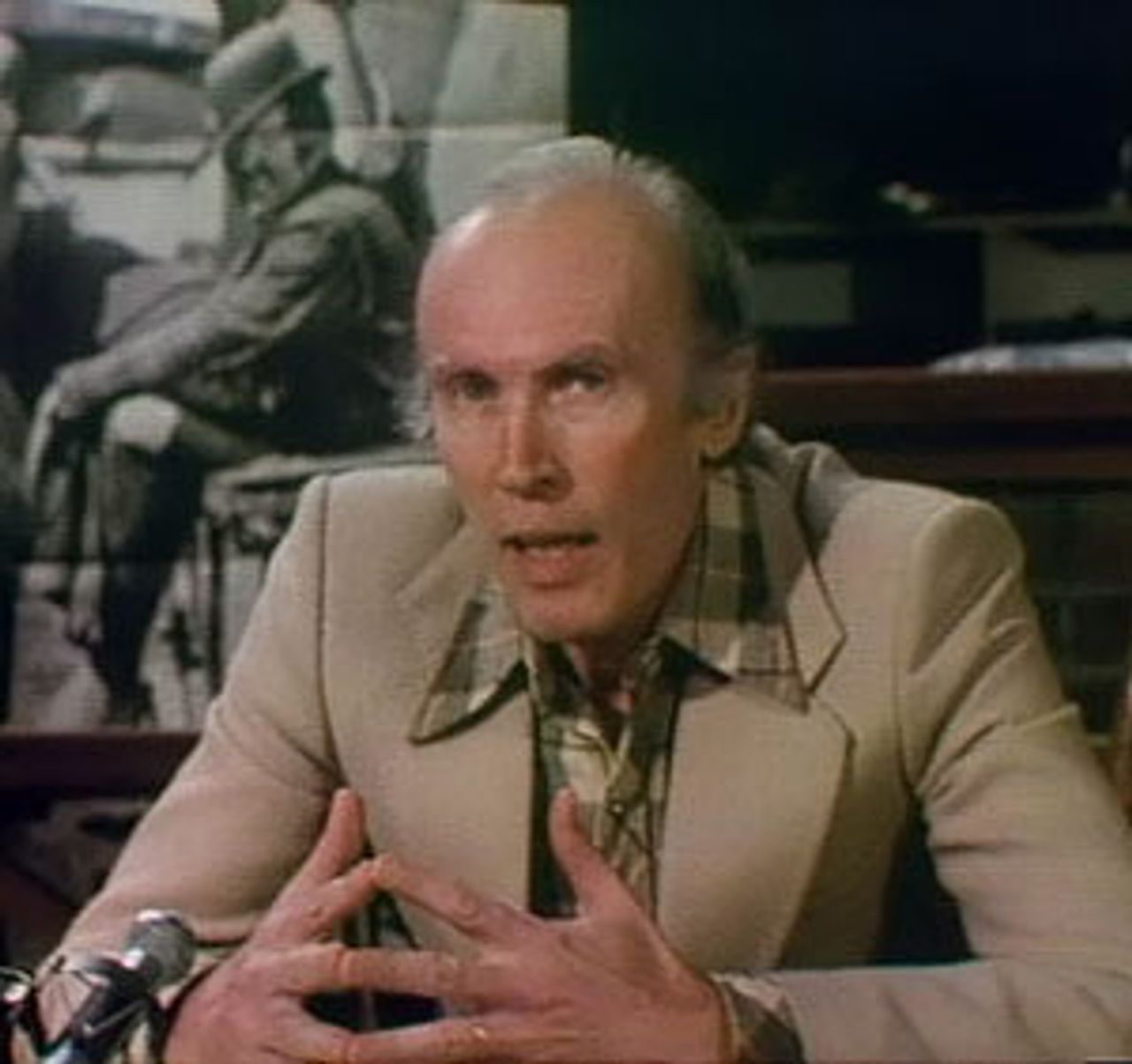

Eric Rohmer

Eric RohmerFrench film director Eric Rohmer died January 11 in Paris, at the age of 89. Rohmer’s work was most prominent in the 1970s and 1980s, although he continued making films until 2007.

He is perhaps best known for My Night at Maud’s (Ma nuit chez Maud, 1969), Claire’s Knee (Le genou de Claire, 1970), Chloe in the Afternoon (L’amour, l’après-midi, 1972), Pauline at the Beach (Pauline à la plage, 1983), Summer (Le rayon vert, 1986), and his four “Tales” of the seasons made throughout the 1990s.

My Night at Maud’s

My Night at Maud’sAt least two things are striking about the release dates of those films: first, that Rohmer was nearly 50 when he entered the limelight, and, second, that he came into his own, so to speak, in the immediate aftermath of the betrayed French general strike of May-June 1968. The significance of this second fact is something that needs to be thought about.

All of Rohmer’s films are intelligent and carefully made, with varying degrees of irony and detachment, portraying men and women in various states of either self-delusion or temptation, or both, as they pursue and reveal themselves in their relationships. “What I say,” he explained once, “I do not say with words. I do not say it with images either.… I do not say, I show. I show people who move and speak. That is all I know how to do, but that is my true subject.” With how much insight and depth he showed people “moving and speaking” remains an issue to be explored.

At present, many uncritical tributes to Rohmer are appearing (including one from the president of France himself), praising the writer-director’s “restrained,” “elegant” and even “sublime” films. A degree of exaggeration is inevitable in the case of a man who continued quietly working away at his craft until near the end, and whose personal conduct, as far as one knows, was above reproach. Moreover, some of the adulation no doubt stems from a sincere desire for a more thoughtful and sensitive approach to filmmaking than we presently confront. However, a measured approach is called for in dealing with the body of Rohmer’s work, which is of a distinctly mixed character, with pronounced and even fatally debilitating weaknesses, and which emerged across a number of complex and turbulent decades.

The filmmaker kept his private life and biography strictly to himself, and some mystery remains about his origins. He was born either Jean-Marie Maurice Schérer or Maurice Henri Joseph Schérer in the provincial city of either Tulle or Nancy, in March 1920. Schérer taught literature and wrote novels before turning to cinema after World War II. Along with a number of others, including Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, and Jacques Rivette, Rohmer (who reportedly adopted the pen name, his second, in the mid-1950s to keep his artistic interests from his family) began writing for André Bazin’s influential Cahiers du cinéma magazine (literally, “Notebooks on cinema”) in the early 1950s.

A great deal of mythology has grown up around the Cahiers du cinéma group of critics, who later formed the core of the “New Wave” (La Nouvelle Vague) in French filmmaking in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Considerable claims were made about their work at the time, but the enduring creative results of the New Wave appear more and more open to question as the years go by.

The group’s members for the most part exhibited an interesting spontaneity (this was never Rohmer’s strong point), concreteness, and flexibility, but they were also guilty of much triviality and self-indulgence. That they by and large ignored the most pressing problems of the postwar years in France, at least until the mid-1960s, is undeniable and discrediting. To help explain how and why such talented individuals remained so indifferent to the social and popular state of affairs, one must bear in mind that the film magazine’s founding in 1951 was bound up with the culture wars in postwar France and that Cahiers du cinema located itself in the “apolitical” or even right-wing camp.

Of course, the situation was very much complicated by the fact that the official left wing of the French literary and film world was dominated by the Stalinist Communist Party and intellectuals in its orbit. There were many reasons for finding that milieu unappealing, including the ferocious Stalinist repression of artists and intellectuals in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, and individuals such as Truffaut and Godard eventually worked their way toward the left. But not everyone who found him or herself on the political right was there by default.

Rohmer, for one, seems to have been relatively clear about where he stood. In a 1983 interview included in The Taste for Beauty, a collection of his essays, the writer-director explains that his first ideological polemics occurred in the context of the Cold War and involved differences between the “political wing” and the “noncommunist wing,” Bazin and others, on L’Écran français (another film journal), in 1949 or so.

Rohmer recalls: “Bazin and [critic-filmmaker Alexandre] Astruc were, for example, the only ones who said good things about American film. During the cold war it was not acceptable to say anything good about American film.… The spirit of opposition [between the factions] is still around from those years.” This is important, and true.

In a review of the Biarritz film festival in Les Temps modernes [Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s journal], also written in the postwar years, Rohmer commented: “If it’s true that history is dialectic, at some moment conservative values will be more modern than progressive values.”

The issue here is not to “indict” Rohmer for his views, but to examine what role his conceptions played in the working out of his art over the next number of decades.

The oldest of the New Wave members, he also began his career the latest and perhaps with the most difficulty. He wrote extensively on film in the 1950s, including a monograph with Claude Chabrol on Alfred Hitchcock, published in 1957. A number of Rohmer’s early short films, including Veronica and Her Dunce (1958), Presentation, or Charlotte and Her Steak (1960), Nadja in Paris (1964), while perfectly watchable, lack inspiration and urgency. His first feature film, The Sign of Leo (1959), about an expatriate American down on his luck in Paris, a more serious effort, did not meet with success.

So Rohmer worked in television documentaries, edited Cahiers du cinéma until 1963, and did not venture into feature filmmaking again until 1966, when he directed The Collector (La Collectionneuse), an odd but affecting film about a triangular relationship. Two male friends, Adrien (Patrick Bauchau) and Daniel (Daniel Pommereulle), expecting to spend an indolent summer in a St. Tropez villa belonging to a third friend, are disturbed by the presence of 20-year-old Haydée (Haydée Politoff), the supposed “collector” of the title—i.e., a collector of numerous boyfriends.

The Collector

The CollectorFor a Rohmer film, there is an unusual degree of verbal violence and antagonistic interaction. Only Haydée, alternately fought over, ignored, manipulated, and occasionally abused by the two self-involved, egotistical men, emerges in an especially sympathetic light. Paying occasional attention as it does to money, ambition, and with elements of satire (in the person of a cynical American art collector), one is tempted to argue that in its tone this is Rohmer’s most socially critical (and self-critical) film—relatively speaking, of course.

Moreover, although it contains a version of the Rohmer formula, as defined by critic Molly Haskell, “[Male] A, who is committed to [Female] B, meets and is tempted by [Female] C, but renounces her in favor of B,” never is this “renunciation” and return to the original woman (in this case, Adrien’s model girlfriend who has gone off to London) more obviously self-serving, insincere, and dubious.

La Collectionneuse is, somehow, an angry and questioning work. The scene in which Daniel, an artist, refuses to sell his work to the American collector and denounces him in no uncertain terms would never be repeated in a Rohmer film. One critic categorizes La Collectionneuse with Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) and Weekend (1968) “as prophetic films whose anti-bourgeois credo” foreshadowed the May-June events.

The film may very well express “stirrings of something to come” (as do Godard’s works), but this needs to be made more precise, especially in the light of Rohmer’s subsequent development. From an objective standpoint, what finds expression in La Collectionneuse tends to be the angry, frustrated mood of sections of the French middle class on the eve of the 1968 upheavals (and which found partial reflection in the student revolts): diminishing prospects and a general sense that the future was bleak for a generation of university-trained professionals; discontent with the commercialization and increasing impersonality of French society; anti-American sentiments bound up with growing US encroachment into European economic and cultural life at French expense; and so on.

Nonetheless, if it is not an appealing film, La Collectionneuse may contain some of Rohmer’s most haunting (and beautiful) images. It even brings certain of Rainer Fassbinder’s films to mind (Beware the Holy Whore, etc.), as unlikely as that now might seem. But then one remembers that Fassbinder dedicated his early film, Love is Colder than Death, to Rohmer and Chabrol, along with several others. Since the German director’s film was shot in April 1969, before My Night at Maud’s came out, it would appear likely that Fassbinder had La Collectionneuse, along with some of Rohmer’s short films and perhaps The Sign of Leo, in mind.

The dates here are significant. La Collectionneuse was released in France in March 1967; Rohmer’s next film, a critical and commercial triumph, My Night at Maud’s, was filmed in December-January 1968-1969 and opened in Paris in June 1969.

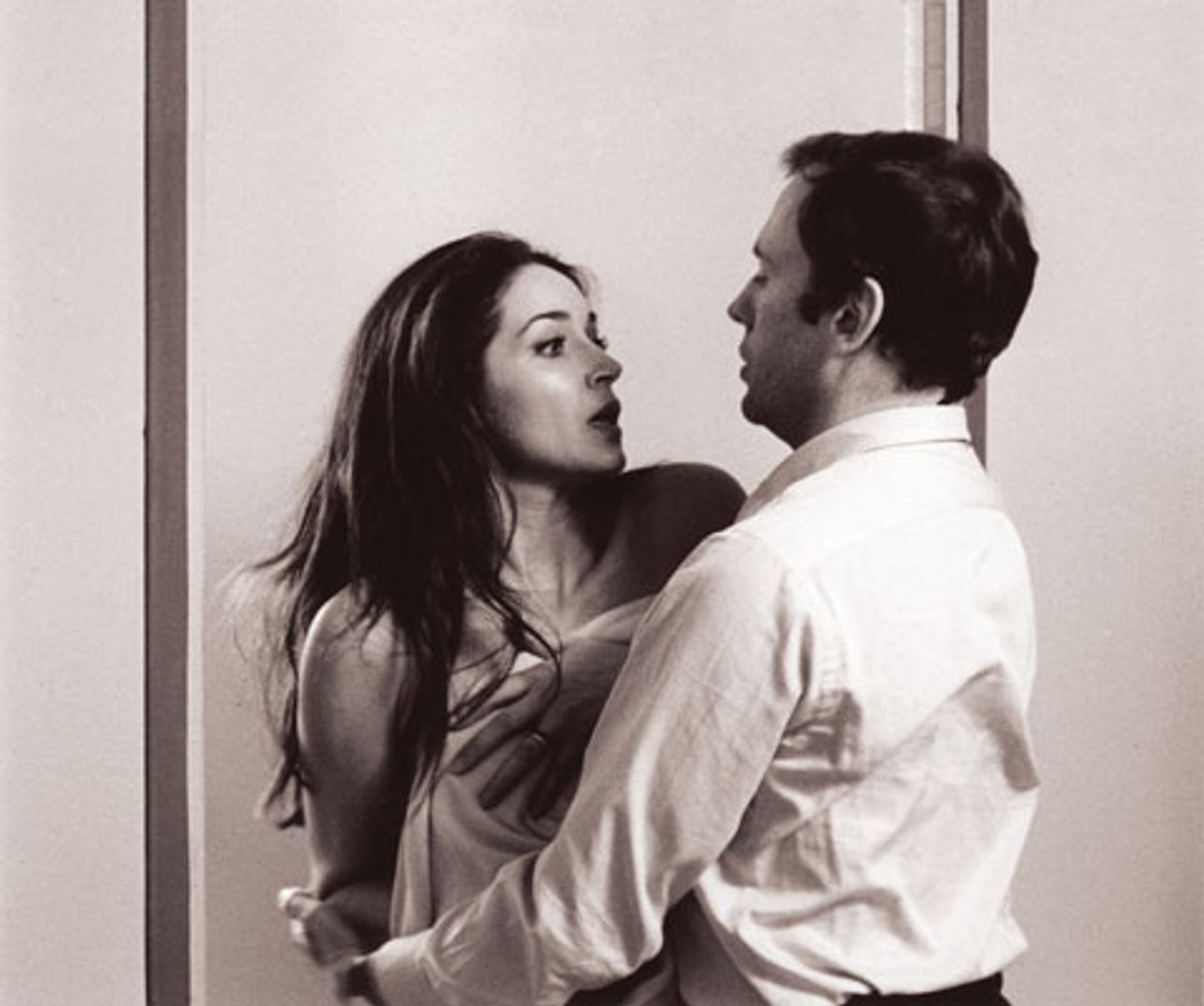

My Night at Maud’s concerns a devout Catholic, Jean-Louis (Jean-Louis Trintignant), who notices a pretty blonde woman in church and determines to marry her without having spoken to her. Vidal (Antoine Vitez), an old classmate and a “Marxist,” invites Jean-Louis to the apartment of the recently divorced and open-minded Maud (Françoise Fabian) for dinner and talk. The weather obliges Jean-Louis to spend the night at Maud’s, whose sexual favors he rejects. He eventually finds his soulmate, Françoise (Marie-Christine Barrault), and marries her.

In many regards, this work is the polar opposite of La Collectionneuse. My Night at Maud’s is shot in black-and-white, in winter, in the cold and snow, in the provinces. The drama unfolds, not in sun-dappled fields and on beaches or in an expansive villa, but, for the most part, in crowded cafes and cramped apartments. The film is tightly done, far more polished, less abrasive, with professional actors and precise timing. Its leading figure is not an artist or art lover, but an engineer for Michelin. The target of the director’s implied criticism is not a wealthy American entrepreneur, but a left-wing professor.

More significantly, in terms of the evolution of Rohmer’s themes, My Night at Maud’s marks a considerable leap. Jean-Louis’ refusal of the sensuous Maud, and “loyalty” to Françoise (a woman he has not yet really met), is more preposterous and rooted in fantasy and superstition (the latter’s looks, their common Catholic faith), and, therefore, far more powerful and convincing. Whatever we may think of Jean-Louis’ choice, we are clearly intended to see his intuitive epiphany about Françoise as carrying considerable spiritual weight, perhaps even as part of a divine plan, or at least as his gamble, à la Pascal, that such a plan exists for him.

One can only deduce from the aesthetic and intellectual facts that the events of May-June 1968, and the threat to the foundations of French capitalism they represented, had a deep impact on Rohmer. It seems to have both energized and alarmed him, driven him toward more serious and widely accessible work, put paid to his “anti-bourgeois” phase, and brought into focus what he valued and what he rejected in life.

This is not meant to imply that My Night at Maud’s represents an artistic or intellectual regression. Life is not so simple. It is, by most standards, a far superior film to La Collectionneuse. There is memorable and incisive dialogue, events that stand out, flawless acting. One recalls, in particular, the conversation between Jean-Louis and Vidal (“To a communist, Pascal’s wager is very real.…”), and the late-night talk between Jean-Louis and Maud, 30 years after a first viewing.

However, My Night at Maud’s set Rohmer on a course from which he would not essentially deviate for the next three decades. It consolidated his dramatic-moral “formula” (the return of A to B, in various forms, and his repudiation of C), in which from now on he had much more of a vested interest.

Is it possible to read too much into Rohmer’s response to the 1968 events? Perhaps, but then perhaps not. No doubt many of the elements of his thinking and his art were already in place. In 1965, in an interview with Cahiers du cinéma, he had declared: “I don’t know if I’m on the right politically, but in any case what’s certain is that I am not on the left. That’s right, why should I be left-wing? For what reason? What’s to compel me? I’m free to choose, aren’t I? Well, people aren’t free. Nowadays you have to make your act of faith with the left, and then you can do anything.…” But the general strike and accompanying events certainly confirmed and accelerated his political and social trajectory.

In any event, the comment in the 1965 interview is self-serving. The issue is not “the left” per se, but an artist’s attitude toward reality and the fate of humanity. What one asks, in the first place, is: Does a particular standpoint encourage or discourage the broadest, most comprehensive, most penetrating view of life? Rohmer dealt with aspects of reality, but avoided many important ones. His characters, one should not have to point out, are almost invariably petty bourgeois, attractive (in at least two films a character, unpleasantly, announces her dislike of “ugly people”), and economically free of care. Removing money pressures from the artistic treatment of love relations alone is to distort them, almost beyond recognition—every significant artist in modern times has understood that.

Claire’s Knee

Claire’s KneeRohmer proceeded from My Night at Maud’s with obvious confidence, to Claire’s Knee (Le genou de Claire) and Chloe in the Afternoon (L’amour, l’après-midi). In the first, a middle-aged diplomat (Jean-Claude Brialy) on vacation is egged on by a friend, a woman writing a novel, to seduce a teenage girl, but he falls for her sister instead, and obsesses about her knee. The events are painstakingly and picturesquely developed, but Brialy, who of course returns to his fiancée in the end, always seemed hopelessly smug. The “formula” is already something of a “formula.”

Chloe in the Afternoon is more interesting, although uglier in its implications. A successful and married young businessman, Frédéric (Bernard Verley), who imagines himself a lady-killer, encounters the former lover (Zouzou) of a former friend. Once a model, Chloe, a bohemian, is now at loose ends, financially and emotionally. She and Frédéric begin meeting, in the afternoons of course, simply to talk, but one thing threatens to lead to another. In the end, Frédéric literally runs back to his tearful wife, leaving Chloe naked on her bed.

Haskell, writing in 1980, was scathing about the film’s conformist intellectual thrust. She refers to “Frédéric’s farcical escape from Chloe and fatuous reunion with his wife, and Rohmer’s vindication of conjugal love” as a “complete capitulation to bourgeois morality, a victory of blindness over (in)sight. Frédéric’s self-deception, his commitment to the idea of an emotion, or a person, instead of to the person herself, is total.… By an association which he [Rohmer] makes inescapable, traditional aesthetic values become linked with reactionary social aims.”

The five films Rohmer wrote and directed between 1981 and 1986, The Aviator’s Wife, A Good Marriage, Pauline at the Beach, Full Moon in Paris, and Summer, reveal the filmmaker’s strengths and weaknesses in even more pronounced form.

The slightest of the five, The Aviator’s Wife and Full Moon in Paris, border on the inane. One feels oneself, frankly, in the territory of American television situation comedies of the decade, those that specialized in stories “about nothing,” or Woody Allen at his most irritating (that is, before his collapse in the mid-1990s).

The other three movies are made remarkable at moments by performances from Marie Rivière, André Dussollier, and some of the younger actors. Summer, about a young woman who can’t decide where to take her vacation, also threatens to topple over into triviality, but Riviére’s strong, unsettling presence at least suggests that something more existential than holiday plans is at stake. And the last moments, as her character waits for a sign from the natural world as to what she should do, are quite moving.

Unhappily, there is little to choose between among A Tale of Springtime, A Winter’s Tale, A Summer’s Tale, and Autumn Tale, made from 1990 to 1998. In attempting to recall them, one tends to forget which film concerned a shy young man who has to choose between a number of women in a seaside town, which one involved a young woman scheming to set her father up with her new acquaintance, which centered on a vineyard owner whose friend wants to pair her off, and which of the four follows a woman still pining for a lover (and father of her child) whose address she unfortunately mislaid. The acting remains textured and precise, the dialogue civilized, and the images crisp, but little else stands out.

In the new century, Rohmer vented his spleen against the French Revolution (and contemporary French society) in The Lady and the Duke (2001), based on the memoirs of Grace Elliot, a Scottish aristocrat trapped in Paris as the overthrow of the old order begins in 1789. We commented on the WSWS: “Veteran French filmmaker Eric Rohmer has joined the chorus of intellectuals and filmmakers who take for granted that the French Revolution of 1789 was one of history’s bloody abominations.… As in all of Rohmer’s work, the revelation and discovery of character occur through bouts of intense dialogue. L’Anglaise et le duc is more of a revelation about its creator’s ideological bankruptcy than anything else. However masterfully Rohmer has digitally recreated eighteenth century Paris, his artistry is subordinated to a very reactionary and stupid goal.”

In conversations with French journalists at the time (ironically enough, in early September 2001), the 81-year-old man made his positions clear. Speaking of anti-royalist Paris, Rohmer noted to Le Monde that it was “comprised of elements that we now call uncontrolled, often people without work, who are looking for adventure, like today’s hooligans.” He used the language of the French right, which stigmatizes the youth of the working class and poor suburbs.

He told Libération that “I think Grace Elliot was mostly right about the Revolution—it was the end of a world, of a refined civilization.” When the newspaper’s interviewer suggested that Rohmer had little sympathy for the people, the latter responded, “Who do you call the people? I am showing mass murderers, the dregs of society, people who killed for pleasure and under the influence of alcohol.… They were manipulated by the politicians, Marat, Danton, Robespierre.… On the other hand, I believe that there exists a good people, calm, who stayed home and who deplored the excesses.”

The interviewer pointed out that this “good people” was not much in evidence in the film. Rohmer replied, “There are nonetheless Grace’s servants.” Precisely…these are the “good people” who know their place and stay at home.

There is this deeply conservative, intellectually blind side to Rohmer which ought not to be ignored. Working class characters in his films? One remembers the retired taxi driver who makes a brief appearance in Summer, who has never been out of Paris, more or less, who has no desire to go anywhere or do anything different. This is the “honest French workman,” who never questions anything too deeply, a loyal servant, to whom Rohmer pays respect.

Everyone in his or her place, doing what he or she ought to be doing—or, rather, because Rohmer is not that simplistic a thinker or an artist, the complex, confusing, indefinite movement toward that desired state of equilibrium. He sees or searches for the presence of a “natural order,” which is to say most probably, a “divine order,” on earth.

The events of May-June 1968 loom large in this career, the revolution that didn’t occur, that he devoutly wishes would never occur. One critic notes that at the center of Rohmer’s series of “Moral Tales” (La Collectionneuse, My Night at Maud’s, Claire’s Knee, Chloe in the Afternoon and a number of the other early films) “one finds lack, the non-event.”

There is this bit of dialogue in Claire’s Knee:

Jerome: And if I don’t sleep with her?

Aurora: The story will be much better, because it is not necessary that something happens.

…

Aurora: For me to write our story, it has to happen.

Jerome: And if it doesn’t happen…?

Aurora: Something always happens, if only your refusal to let something happen.

How appropriate is it for a conservative film director, in the land of revolutions, during a reactionary time, to celebrate and cherish the event that doesn’t happen, that mustn’t happen?

One forgets too much of Rohmer’s work. It is not the intimacy, the working in detail as such, but the failure to turn the details of life into immense drama. Great drama corresponds to contradictory movement and change, processes that Rohmer feared and resisted. From the ideological point of view, we are witness to a prolonged argument against social revolution, the unknown, the future different from the present.

Instead, we have circularity, regularity, the movement of the seasons, French summer vacations that always end on time, the back and forth from Paris to the countryside, or from the city to the suburbs. Trains! Trains between cities, subway trains, commuter trains. Movements on schedule—one goes somewhere, but one is always guaranteed to return to the same point, one is imprisoned on tracks. How comforting.

In 2008, we commented, at the time of his final film’s appearance, The Romance of Astrea and Celadon: “Rohmer will be remembered for his intelligent considerations of the moral struggles (or sweatings) of the French urban middle class in the post-1968 era. His is a universe in which social upheaval lies decisively outside the frame. Rohmer’s first great success, My Night at Maud’s, significantly, came in 1969. His works have alternated between the self-involved and trivial, on the one hand, and the emotionally acute and quasi-satirical, on the other. No one, however, has ever questioned his sensitivity and intelligence.

“Age is one crisis that befalls everyone, but a few years ago, Rohmer said he had run out of stories to tell. What could that mean but that the ‘post-1968’ period in which he flourished was coming to an end in France, along with the relations and social psychology with which it was associated, and a pre-’something quite different’ was emerging?”