The Automatiste Revolution: Montreal 1941-1960: The Varley Art Gallery, Unionville, Ontario, until Feb. 28, 2010; The Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, March 19 to May 30, 2010

The Varley Art Gallery in Unionville, Ontario, just north of Toronto, is hosting what has been called “the show of the year” in Canada, bringing together the work of 15 artists known as the “Automatistes,” which deserves attention for a variety of reasons.

The name refers to a practice of the Surrealists known as automatic writing (i.e., supposedly writing—or creating generally—without the intervention of conscious thought) and was given to a group of artists in Montreal who, notwithstanding their relative obscurity, provoked a political storm in post-war Quebec and were in the vanguard of modern art in the 1940s and 1950s.

Like the Surrealists, the Automatistes regarded the development of art as a wider project that brought them to challenge what they viewed as an intolerable social and artistic state of affairs—in a body of work that spanned various disciplines and which is represented in the current exhibition by more than 60 art works and displays.

Paul-Émile Borduas, Bercement silencieux, 1956, Estate of Paul-Émile Borduas / SODRAC (2008)

Paul-Émile Borduas, Bercement silencieux, 1956, Estate of Paul-Émile Borduas / SODRAC (2008)With artist and teacher Paul-Émile Borduas as their leader and spokesman, the Automatistes were inspired by the oppositional spirit of the Surrealists as articulated by André Breton and others in the inter-war period. The pieces selected for the exhibition are drawn from numerous collections and sources and show critical moments that collectively provide an informative record of the group’s evolution.

Consequently, the exhibition focuses on material chosen as much for its historic as its aesthetic interest, which doesn’t necessarily result in the display of the artists’ finest work. The show includes a charming, if eccentric, film recreation of a solo dance staged in a rural Quebec winter, as well as selections of poetry, design and sculpture—in addition to an impressive collection of paintings that constitute its core.

Although the exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue co-written by art historians Roald Nasgaard and Ray Ellenwood, which provides some useful commentary, for those unfamiliar with this art and its environment something more is required to understand its significance.

Surreal to abstract

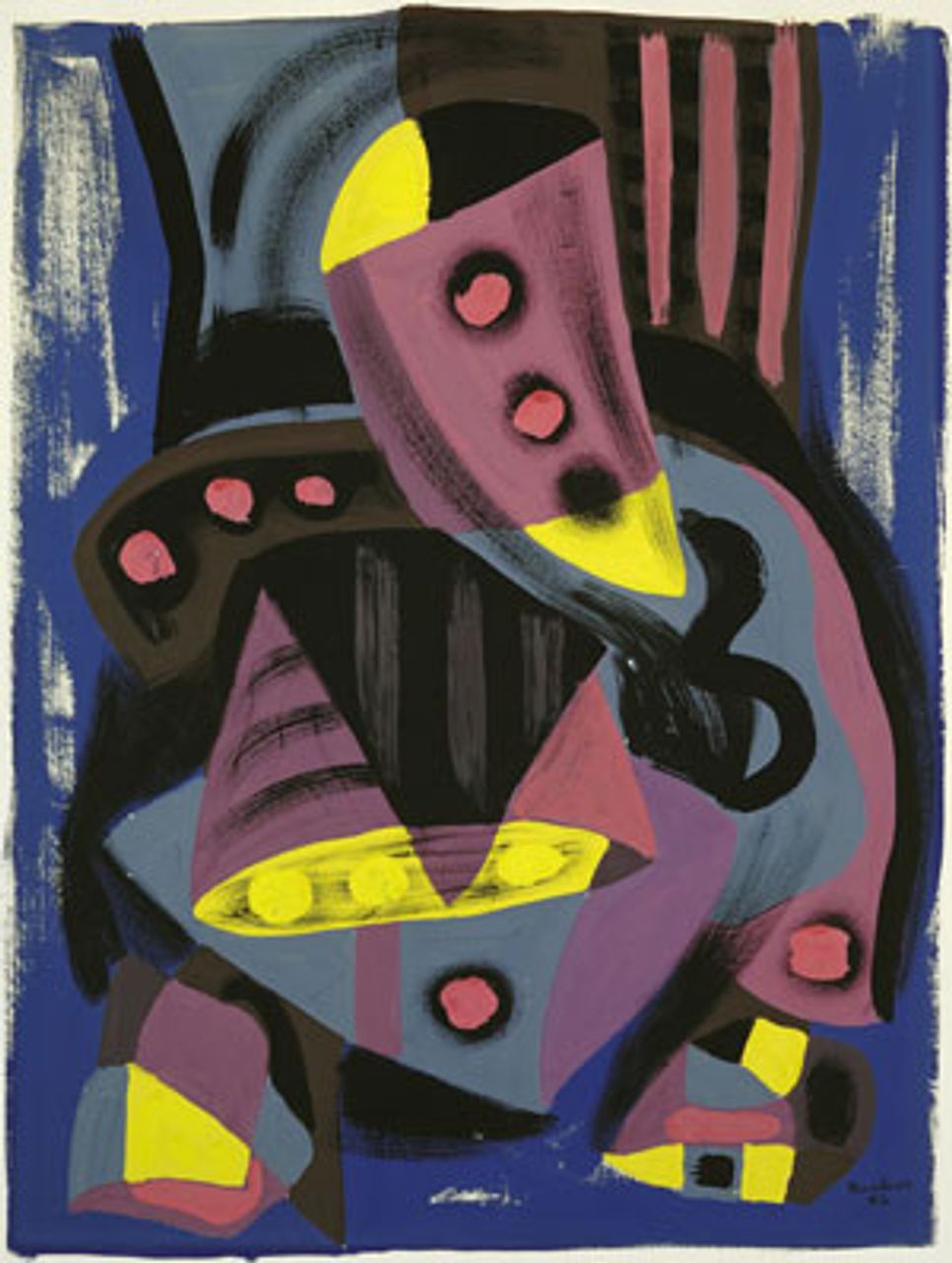

Paul-Émile Borduas, Composition, 1942,

Paul-Émile Borduas, Composition, 1942, Estate of Paul-Émile Borduas / SODRAC (2008)

Various terms are used to describe the painting styles developed by this group from Tachism in Europe (from the French word for stain, tache), or otherwise Gestural or Lyrical Abstraction, but the innovations of the Automatistes clearly paralleled those of the Abstract Expressionists in New York in their non-representational and spontaneous approach. Though not as well known as some of the New York School, the Automatistes include such noted artists—in addition to Borduas—as Jean-Paul Riopelle, Pierre Gauvreau, and Marcel Barbeau, whose works trace a remarkably similar development to their American counterparts.

With Paris at the centre of modern art before the war, and New York after it, artistic life in Montreal would have been relatively isolated from international currents. Still, some of the city’s leading artists travelled and studied abroad and were deeply influenced by developments in both Europe and the US.

With the simple and modest work, Green abstraction, painted in 1941, Borduas announced a new direction for abstract art that came to attract a number of his students, some of whom, like himself, had been trained to produce ecclesiastical art. These early paintings broke new ground in what came to be known as “Color Field” and “Action” painting, which can be seen in a number of the works in this exhibition.

Marcel Barbeau, Rosier-feuilles, 1946, © Marcel Barbeau / SODRAC (2008)

Marcel Barbeau, Rosier-feuilles, 1946, © Marcel Barbeau / SODRAC (2008)In addition, paintings such as Barbeau’s Rosier feuille (Rosebush leaves) in 1946, while not perhaps his most successful work, also took a new direction and anticipated the drip paintings of Jackson Pollack only a couple of years later, although there was no apparent contact between the artists. A subsequent piece that is also in the exhibition, Barbeau’s Au château d’Argol (1946-1947), is one of the more powerful and effective paintings of this genre.

Borduas described this new direction as “an art form entirely devoted to the exploration of the internal world, and one that marked the end of the attempt, followed up until this point, to represent the external world.”

Although, for the Automatistes (and other trends globally), there may have been no conscious connection between their move away from representation and towards abstraction, on the one hand, and a turn from the social to the largely personal, on the other, the respective transitions were unquestionably bound up with changes in the objective situation. In light of difficult prevailing conditions, this has to be seen as a retreat in the face of what were seen as problems insoluble from a political standpoint.

While the Surrealists in general used recognizable imagery in their work, although in often startling combinations and juxtapositions, artists like Borduas wanted to preserve what they took to be that movement’s spirit, but without its revolutionary oppositional content. This “excision” is not a small matter, and it shows the weight of the historical and social difficulties by the post-war years.

Whereas Breton denounced the hypocrisy and crimes of the bourgeois order and called for its overthrow, Borduas turned inward in despair at any political way forward, and toward supposed individual, spiritual salvation.

In Quebec, the difficulties were compounded by a stifling political and artistic climate that left the artists isolated and desperate for a means to affect change in their world.

Artists in revolt

With the publication in 1948 of their manifesto, “Refus global” (or “Total refusal”), the newly formed Automatiste group came into direct conflict with the repressive regime of Premier Maurice Duplessis (1936-1939, 1944-1959), allied with the Catholic Church in a period that came to be known as “La grande noirceur” (“The Great Darkness”).

After coming to power in Quebec in 1936, Duplessis quickly oversaw the passage of the infamous “Padlock Law,” which allowed the provincial government to lock any building allegedly used for disseminating “communism” or “Bolshevism,” and to ban any materials advocating such ideas.

Following the war, although Duplessis had been returned to power, Quebec experienced an upsurge in working class militancy that culminated in 1949—the year following the publication of the Automatiste manifesto—in the strike by thousands of miners in Asbestos, one of the most bitter, violent labor conflicts in Canadian history. Duplessis sent squads of police to protect the mines and break the strike during its four months, leading to mass arrests and beatings of miners. The ruling elite’s sensitivity about the call for revolt in the Automatistes’ statement, however muted, may be understandable.

The artists’ manifesto was signed by Borduas and 15 others, and was a broad assault on the collusion of the Catholic Church and the political elite in Quebec in the effort to strangle artistic and political freedoms. The manifesto denounces “the forces of oppression that had made of Quebec a suffocating environment, hostile to both individual and collective creativity.”

Although the manifesto forcefully exposed the rotten state of things, it did not propose to set them right politically. Bourduas openly declared his scepticism about any such project, stating that “For centuries, splendid revolutions fought by people who believed in them utterly have been crushed after one brief moment of delirious hope in their barely interrupted slide toward inevitable defeat.”

Borduas hoped that art by itself would provide the means for creating a kind of utopia—as he puts it—“toward the joyful fulfilment of our fierce desire for freedom.”

Pierre Gauvreau, Colloque Exhubérant, 1944, © Pierre Gauvreau / SODRAC (2008)

Pierre Gauvreau, Colloque Exhubérant, 1944, © Pierre Gauvreau / SODRAC (2008)The pamphlet containing the manifesto was authored by four other artists of the Automatiste group, in addition to Borduas: Bruno Cormier, who became a psychoanalyst; poet Claude Gauvreau; painter Fernand Leduc; and dancer and choreographer Françoise Sullivan. The 400 copies that were printed sold out quickly.

Even though the statement had a relatively small audience at the time, official reaction was uniformly and deeply hostile. In the weeks that followed, the Automatistes were subject to vilification by the Quebec government, the Catholic Church, and the media, with virtually no important voices coming to their defence. As a result, many of the Automatistes were victimized, in particular Borduas, who was fired from his teaching position at the École du Meuble (School of Furniture Design) the following month and was never able to teach in the province again.

Borduas published a second text some months later, with a more conciliatory tone, but to little avail. He spent most of his remaining career outside the province, and his official rehabilitation took place only after his death in 1960.

The wartime had seen an influx of immigrants to the province, as well as the transfer of the printing operations of a number of publications from France to Quebec, which together helped foster a cultural awakening. With the post-war reaction having set in, something of the reverse took place. Borduas, Riopelle and others moved to Paris or New York, both to flee harassment at home and to take part in more enlightened artistic environments in those centres.

The subsequent development of industry and the mass emergence of the working class in the 1950s and 1960s cleared away a lot of the old rubbish in Quebec, without of course touching the fundamental class and property relations. It was not until this process was well underway that the rebellion hailed in “Refus global” was taken up by a subsequent generation of artists, activists and intellectuals in the 1960s, without, however, in many cases, the original ferocity of the Automatistes.

Almost inevitably, despite their hostility to the status quo and their explicit rejection of politics in general, the Automatistes have been claimed by vying wings of the establishment, including Quebec and Canadian nationalists. Even gallery director John Ryerson packages them as national icons, declaring that “the Automatistes contribution to Canadian art history outshines that of the Group of Seven.”

The subsequent fate of its reputation notwithstanding, this relatively obscure group of artists in Montreal was able not only to assimilate important artistic tendencies of the day, but also to confront some of the most troubling issues then posed for art and artists.

With what success and to what end remain questions. Although a number of works from this group, particularly the paintings, continue to have appeal for their audacity and lively inventiveness, much of the work in the exhibition seems to belong to a bygone era. Did not the group’s exclusive devotion “to the exploration of the internal world,” while perhaps difficult to avoid given the unfavourable social circumstances, prove a blind alley in the end?

The artistic and social problems of the post-war years have not gone away. On the contrary, they are more acutely posed than ever. Nonetheless, the efforts of artists such as the Automatistes need to be understood both for their courage and commitment, as well as for their limitations.