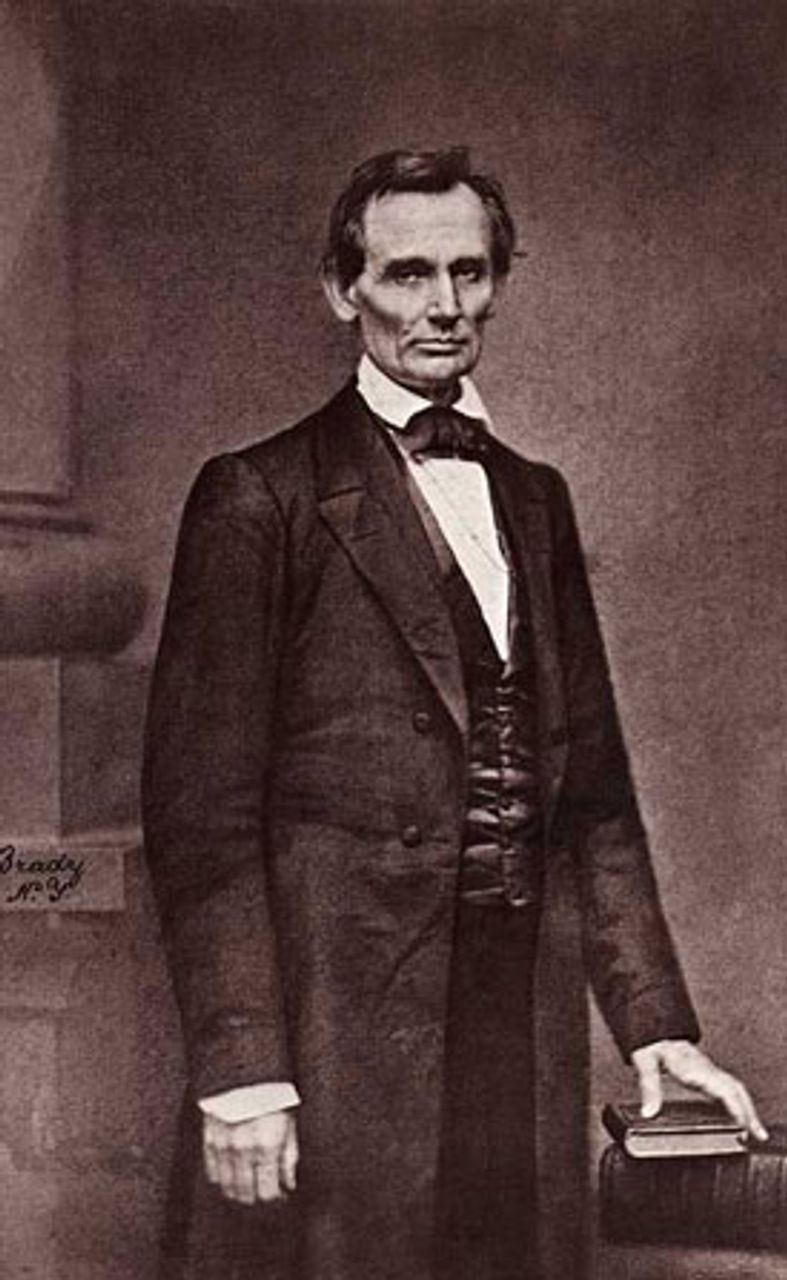

Lincoln in 1860

Lincoln in 1860On December 20, 1860, six weeks after voters of the United States elected Abraham Lincoln as the 16th president, South Carolina seceded from the union. Other Southern states soon followed, leading within little over five months to the outbreak of the American Civil War, the bloodiest conflict in US history, and ultimately to the freeing of four million slaves.

The Southern slave-owning class viewed the election of an anti-slavery administration as a mortal threat. Though not an abolitionist, Lincoln was an opponent of slavery and determined to use all means at his disposal to stop its spread.

“A Party founded on the single sentiment of ...hatred of African slavery is now the controlling power,” wrote the Richmond Examiner of Lincoln’s election. The New Orleans Delta declared no one can any longer “be deluded...that the Black Republican Party is a moderate party. It is in fact essentially a revolutionary party.” (1)

In the ensuing secession crisis Lincoln played a critical role, coming to express the growing public sentiment for resistance to the ever more provocative actions of the southern slavocracy and the policy of capitulation pursued by the outgoing administration of Democrat James Buchanan.

In moving to break up the union the South carried out what noted Civil War historian James McPherson of Princeton University called a “pre-emptive counterrevolution,” using a term he borrowed from historian Arno Mayer. “Rather than trying to destroy the old order, a pre-emptive counterrevolution strikes first to protect the status quo before the revolutionary threat can materialize.” (2)

In other words, sensing that the tide of historical development was moving against it, the southern planter aristocracy chose to instigate civil war rather than accept any restrictions on slavery, the source of its power and wealth. It would not be the last attempt by a retrograde social order to employ violence in order to evade the verdict of history.

The mayor of Vicksburg, Mississippi called secession “A mighty political revolution which [will] result in placing the Confederate States among the independent nations of the earth.” (10-3n)

McPherson replies, “What were these rights and liberties for which Confederates contended? The right to own slaves; the liberty to take this property into the territories; freedom from the coercive powers of a centralized government.” (4)

Or as Massachusetts abolitionist Edmund Quincy wrote in December 1860, “We are on the eve of the oddest Revolution history has yet seen. A Revolution for the greater security of Injustice and the firmer establishment of Tyranny.”(5)

The election of Lincoln brought to a head the sectional struggle over the question of slavery that had been left unresolved by the American Revolution. Far from gradually dying out, as the revolutionists of 1776 had hoped, after the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 slavery expanded rapidly in the early decades of the 19th century. The Democratic Party, founded during the administration of Andrew Jackson (1829-1837), became the political vehicle for the most rapacious section of the Southern planters. It sought not the status quo, but the expansion of slavery across the Americas.

The slavocracy, acting through the Democratic Party, advanced ever more provocative pro-slavery policies, increasingly inflaming public opinion in the free states. In 1846 the Democratic administration of James K. Polk instigated war with Mexico in a land grab aimed at opening to slavery vast new territories to the west. When, in 1850, California was admitted to the union as a free state, the South responded by forcing a punitive fugitive slave law through Congress requiring citizens to actively assist in the capture of runaways.

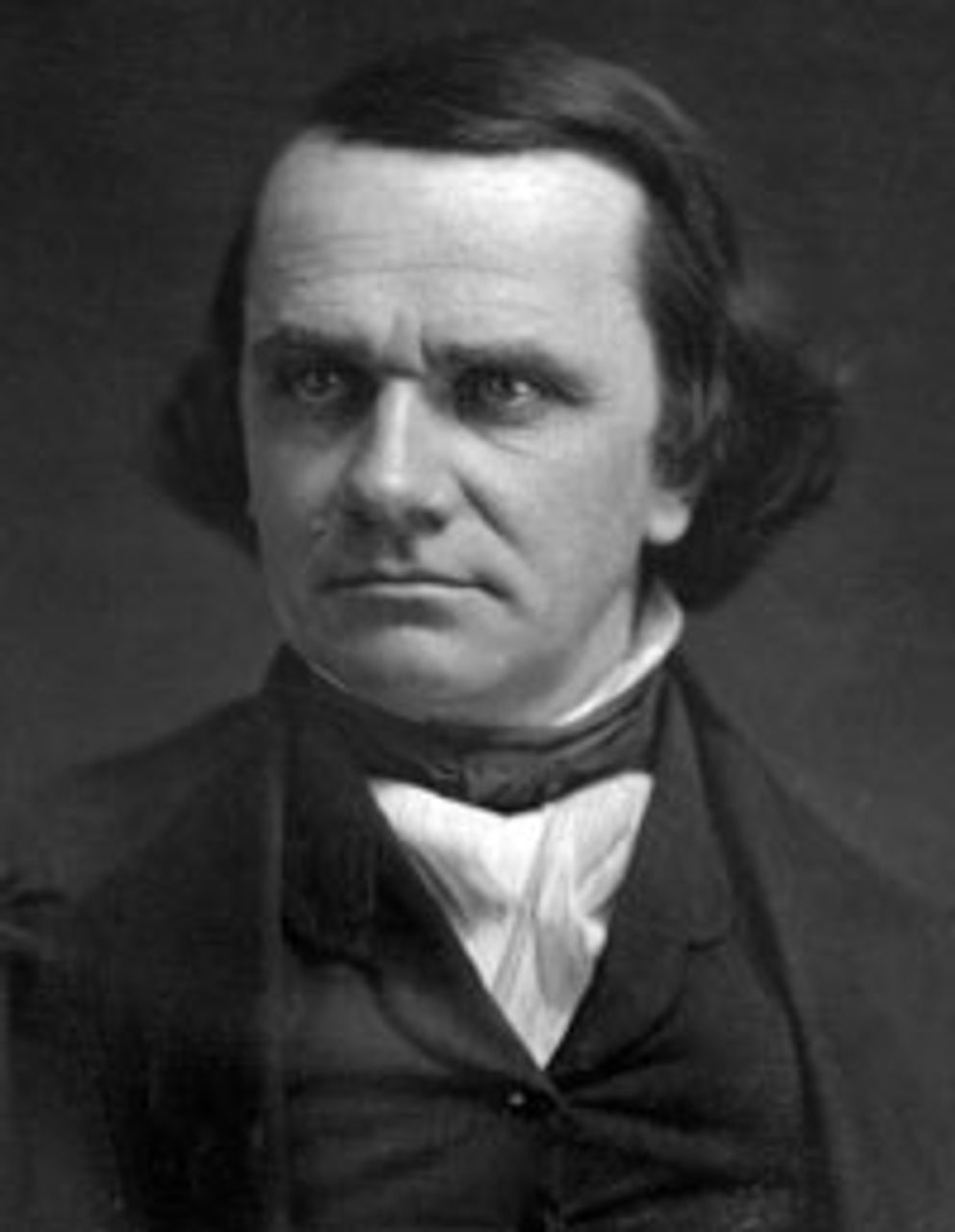

Stephen Douglas

Stephen DouglasIn 1854 Illinois Democrat Stephen Douglas crafted the Kansas-Nebraska Act, with explosive results. Kansas-Nebraska repealed the Missouri Compromise, which had banned slavery in the territories of the Louisiana Purchase north of latitude 36 ° 30’. Instead, it allowed voters in the territories to decide the question of slavery, the doctrine of so-called popular sovereignty. It marked a decisive break with long established precedent, for the first time removing all federal restrictions on the spread of slavery into the territories.

The immediate result was the development of armed conflict in Kansas, where pro-slavery forces attempted to terrorize opponents of slavery. In one of the most notorious incidents, a pro-slavery militia burned the anti-slavery capital of Lawrence. These outrages inflamed sentiment in the North. Abolitionists supplied arms and money to anti-slavery settlers in Kansas to meet the attacks blow for blow.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act brought Abraham Lincoln back into politics. In 1848 Lincoln had retired to his Illinois law practice after one year in the US Congress, where he had unsuccessfully joined an effort to pass legislation barring slavery in the lands annexed during the Mexican-American War. Lincoln soon emerged as an eloquent and forceful opponent of the expansion of slavery.

Kansas-Nebraska led to a radical realignment of political forces. The old Whig Party, which had been based on sectional compromise, collapsed. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party became more and more divided along sectional lines.

The Republican Party, founded in 1856 on a platform opposing further concessions to the slavocracy, united anti-slavery Whigs and anti-Kansas-Nebraska Democrats. It polled 1.3 million votes in the presidential election of that same year. Lincoln joined the Republican Party and campaigned for its candidates.

The Dred Scott decision of 1857 added to political tensions. Dred Scott, a slave, sued for his freedom on the grounds that he had lived for an extended period in Illinois and the Wisconsin territory, where slavery was illegal. In a reactionary and provocative ruling the Supreme Court held that Scott had no standing to sue since blacks were not citizens and had no constitutional rights. Further, the court declared that Congress had no right to restrict slavery in the territories.

Lincoln and Douglas

Lincoln came to national prominence in 1858, when he ran as the Republican candidate for the Illinois Senate against Douglas. A series of debates with Douglas attracted large audiences and newspapers in the east carried transcripts of Lincoln’s speeches.

While Lincoln insisted he had no intention of rolling back slavery where it already existed, he called slavery, “a moral, social and political wrong.” In his “House Divided” speech Lincoln declared that “this Government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.” He hoped, “the opponents of slavery, will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction.” (6)

Lincoln at this point did not advocate social equality for blacks. Still, his views were in advance of majority opinion of the time. He held that Thomas Jefferson’s insistence that “all men are created equal” contained in the Declaration of Independence applied to blacks as well as whites. “The negro is included in the word ‘men’ used in the Declaration,” he declared. This “is the great fundamental principle on which our free institutions rest.” He continued, “In the right to eat the bread, without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and he is the equal of every living man.” (7)

It was Lincoln’s unequivocal insistence that the principles elaborated by Jefferson applied equally to all that won the undying enmity of the Southern planters. They were not satisfied with Lincoln’s pledge that he would not interfere with slavery. The South demanded that slavery be declared a positive good.

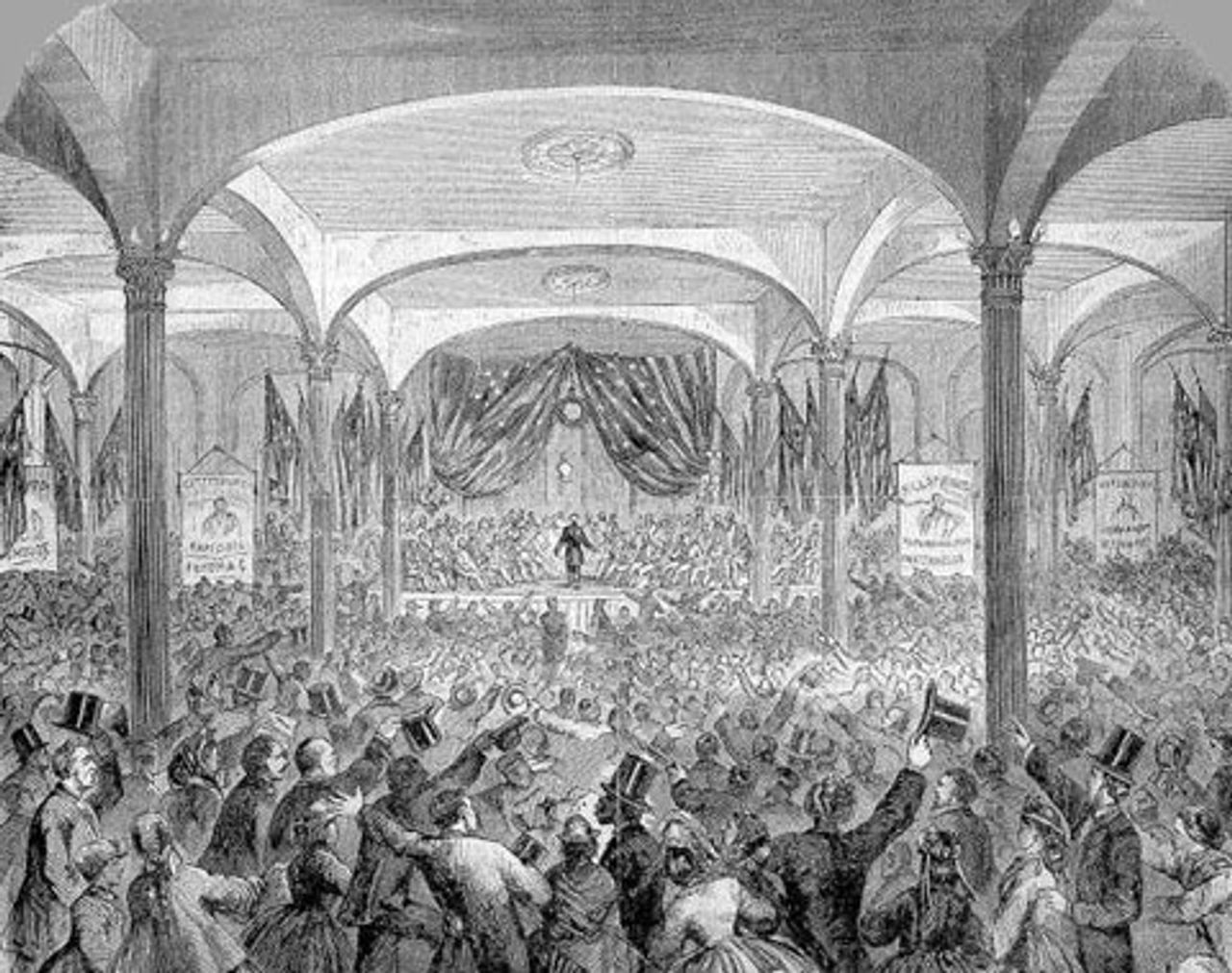

Lincoln speaking at Cooper Union

Lincoln speaking at Cooper UnionIn his famous 1860 address at Cooper Union in New York, which set him on the course to win the Republican nomination for the presidency a few months later, Lincoln, rhetorically addressing the South, declared, “Your purpose then, plainly stated, is that you will destroy the Government, unless you be allowed to construe and enforce the Constitution as you please, in all points in dispute between you and us. You will rule or ruin in all events.”

He asked rhetorically the question, “What will satisfy them?”

He answered, “This and only this: cease to call slavery wrong and join them in calling it right. And this must be done thoroughly—done in acts as well as in words.”

The Republican convention met in May in Chicago at the newly constructed Wigwam. New York Senator Seward expected to win on the first ballot. However, many in the Republican Party felt Seward could not be elected because he was not popular outside of the East. Opponents of Seward launched an effort to block his victory on the first ballot, nominating a host of “favorite sons.” The Chicago Tribune launched an all out editorial campaign in support of Illinois native Lincoln, whose humble origin—he had been born in a log cabin and worked as a flatboatman and rail-splitter—stood out in sharp contrast to Seward, who was identified with eastern banking interests.

On the first ballot Seward failed to achieve a majority of 223 votes, winning 173 ½ votes, to Lincoln’s 102, with 147 ½ going to other candidates. Lincoln’s total rose to 181 on the second ballot. Lincoln then obtained a majority on the third ballot, after his supporters won the support of delegates backing Ohio Governor Salmon P. Chase.

The Republican platform called for a ban on slavery in the territories. It also appealed to small farmers, with a plank calling for passage of a homestead law, giving free land to anyone willing to work it.

While anti-slavery forces united behind Lincoln, the slavery question split the Democratic Party along sectional lines. Southern Democrats walked out of the April nominating convention when they were unable to impose a radical pro-slavery platform and, in particular, the demand that slavery be permitted in the territories and protected there by the federal government. The Douglas Democrats were not prepared to go that far, holding to the doctrine of popular sovereignty.

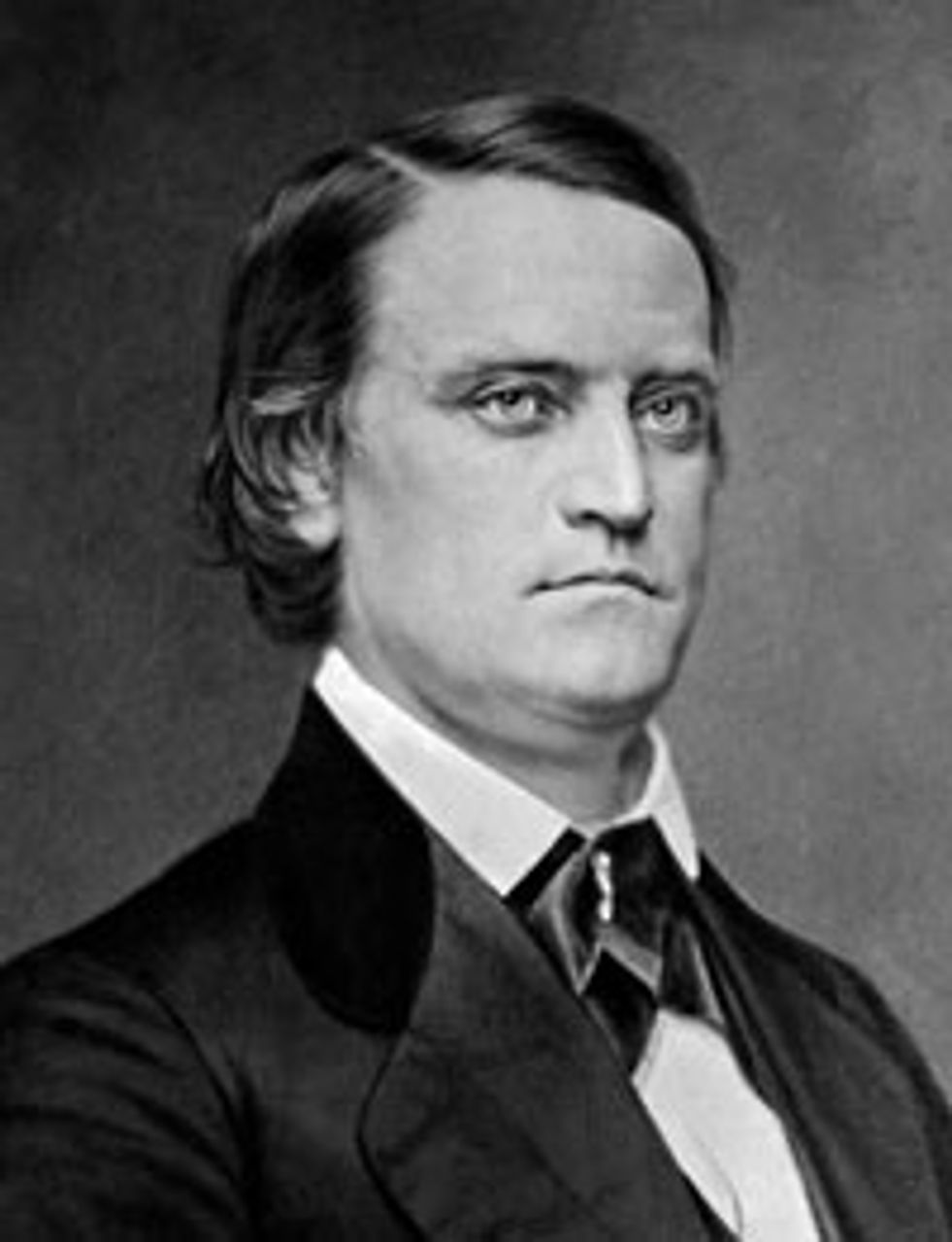

John C. Breckinridge

John C. BreckinridgeThe Democrats reassembled in Baltimore in June, where Northern delegates nominated Douglas with a simple majority. Southern delegates again walked out, this time calling their own convention in Richmond, Virginia where they nominated John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, vice president in the administration of James Buchanan.

A further fracture in the ranks of Lincoln’s opponents occurred when former Whigs nominated the aging John Bell, a wealthy Tennessee slave owner. Attempting to straddle the Republican and Democratic camps, Bell took no position on slavery, calling only for the preservation of the union.

Campaign polarized

The presidential campaign of 1860 was the most polarized and tense in American history. In the North the contest was between Douglas and Lincoln; in the South, between Bell and Breckinridge. The Republicans did not even attempt to field a ticket in 10 Southern states, where their speakers would have likely faced physical attack.

When, early in the campaign it became apparent that the split in the Democratic Party would probably result in the election of Lincoln, near hysteria gripped large areas of the South. The press spread rumors of abolitionist plots to arm slaves. Those suspected of Northern sympathies were hounded and even lynched.

Increasingly, talk spread of the South breaking up the union in the event of a Republican victory. Lincoln refused to be intimidated by threats of secession, rejecting requests to make conciliatory overtures to the South.

As the fateful election approached the Charleston Mercury warned, “The terrors of submission are tenfold greater even than the supposed terrors of disunion.”(8)

In the final polling Lincoln won a plurality of 40 percent of the popular vote. He carried every free state except New Jersey. This translated into a comfortable victory in the Electoral College, because of its winner-take-all system of apportionment. Lincoln won 180 electoral votes, to 72 for Breckinridge, 39 for Bell and just 12 for Douglas, who, despite his poor showing in the electoral college, came in second in the popular vote, polling 1.3 million votes to Lincoln’s 1.8 million.

Opponents of slavery celebrated the Republican victory. The noted African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass declared that Lincoln’s election meant the slave power no longer would rule the nation. “Lincoln’s election has vitiated their authority, and broken their power...More important still, it has demonstrated the possibility of electing, if not an abolitionist, at least an anti-slavery reputation to the presidency.” (9)

The reaction in the South was swift. “They know that they can plunder and pillage the South, as long as they are in the same union with us,” wrote a New Orleans newspaper reacting to Lincoln’s victory. “They know that in the Union they can steal Southern property in slaves, without risking civil war, which would be certain to occur if such a thing were done from the independent South.” (10)

The day after the election the South Carolina state legislature, called into special session by the governor, voted to set December 17 as the date for a special convention to consider secession. The legislatures of Georgia and Mississippi soon followed.

Following a unanimous vote for secession on December 20, South Carolina called on other southern states to join it in the formation of a “great slaveholding confederacy, stretching its arms over a territory larger than any power in Europe possesses.”

In the North financial markets panicked over fears of Southern borrowers repudiating their debts. For his part Lincoln, at least publically, refused to admit that the South seriously intended to break up the union. “Things have reached their worst point in the South and are likely to mend in the future,” Lincoln told a Philadelphia newspaper just days before the South Carolina secession convention. (11)

At the same time Lincoln refused to entertain proposals from some Republicans for political concessions to placate the southern slavocracy, declaring he did not want to put anything on record making it “appear as if I repented for the crime of having been elected, and was anxious to apologize and beg forgiveness.” (12)

Under the procedure set down in the American constitution, although elected in November, Lincoln would not take office until March. In the meantime, the lame duck Buchanan administration temporized and evaded responsibility in the face of the mounting secession crisis. In an address to the last session of the 36th Congress on December 3, 1860, Buchanan insisted that Congress had no “power to coerce into submission a state that is attempting to withdraw.”

Buchanan denounced the Republicans for provoking the South with anti-slavery agitation and counseled the Republicans to support a constitutional amendment protecting slavery in all the territories.

Meanwhile, Democratic Senator John J Crittenden advanced a proposal containing six constitutional amendments and four Congressional resolutions aimed at placating the South. It promised to permanently protect slavery where it already existed, including the District of Columbia. It would have extended the Missouri Compromise line westward, with slavery federally protected south of the line.

Lincoln’s early opposition to the Crittenden proposals, and indeed, any further compromise with the slavocracy, proved decisive in stiffening popular resolve to oppose the demands of the South. Initially some Republicans, most notably Seward, were inclined to accept the Crittenden amendments. However, as the seriousness of the secession threat became ever clearer, public opinion turned against the policy of capitulation to the slaveowners and a broad sentiment began to emerge for resistance. In this process Lincoln came to play a crucial role.

“No concession by the free States short of surrender of everything worth preserving and contending for would satisfy the South” Lincoln told Illinois Republican Orville Hickman Browning, stating his opposition to the Crittenden proposals. (13)

Attention soon focused on the fate of the few forts in the South that were still in federal hands. Whether or not the federal government decided to defend these forts would determine if it was serious about opposing secession.

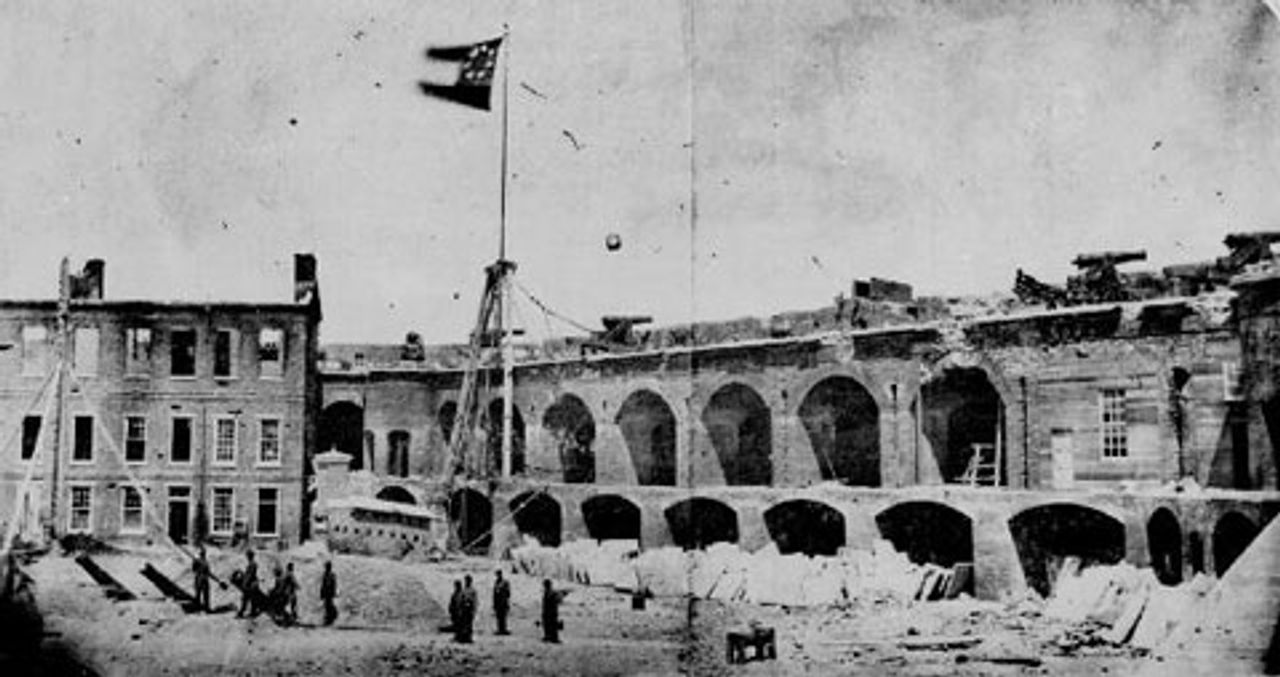

April 14, 1861: The Confederate flag is raised over Fort Sumter

April 14, 1861: The Confederate flag is raised over Fort SumterActing on his own initiative a few days after the South Carolina legislature voted for secession, the commander of the garrison of Fort Moultrie in Charleston decided to move his troops to the more powerful and less exposed Fort Sumter on an island in the middle of Charleston harbor. Meanwhile, Lincoln passed word to General Winfield Scott, commander of the US army, to hold or, if necessary, retake the fort.

For its part the states of the Deep South showed little interest in compromise over secession. “No human power can save the union, all the cotton states will go,” wrote Jefferson Davis on December 30, 1860. (14)

On February 4, 1861 delegates from seven states of the lower South met in Montgomery, Alabama to form a government, issuing an appeal to the remaining slave states to join them.

While the Buchanan administration sat passively by, the Confederate states seized federal property within their borders: customs houses, post offices, mints, arsenals and forts.

During the winter of 1860 eight slave states in the Upper South still held back from joining the Confederacy, prompting some within the Republican Party to urge a policy of waiting, lest hasty action provoke their secession.

In his inaugural address, Lincoln spoke in conciliatory terms, again offering to protect slavery where it already existed. At the same time he pledged to “hold, occupy and possess” federal property in the South and collect duties and imposts. However, the wording left it somewhat ambiguous whether or not this would involve the use of armed force.

Events soon forced Lincoln to act. In South Carolina the commander of Fort Sumter informed Washington that he only had a few weeks of supplies left, after which time he would have to abandon the fort. To the Confederates Sumter was a particularly odious symbol of federal authority—it had resisted all calls to surrender. The Confederacy was now attempting to starve out the garrison, ringing the harbor with artillery and blocking resupply.

Lincoln had the choice of either attempting to resupply the fort, which threatened to spark armed conflict, or hand it over to the Confederacy. Within his cabinet Lincoln found little support for resistance. General Scott also wanted to abandon the fort. Despite this opposition, Lincoln made the principled decision during the last weeks of March that Sumter had to be defended.

Public pressure also mounted on the administration to fight. Many Republicans were angered at suggestions that Sumter might be surrendered to the rebels. “If Fort Sumter is evacuated the new administration is done forever” read a typical letter from a citizen. (15)

While Lincoln was aware that the resupply effort had little chance of success, he ordered that an attempt be made, realizing that defeat in battle was preferable to the demoralizing impact on public opinion of capitulation without a fight. In any event, the South struck first, attacking Fort Sumter on the morning of April 12. The fort surrendered after a 34-hour bombardment.

The attack on Sumter had an electrifying effect on the North, rallying the public behind Lincoln. On April 15, Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion and summoned a special session of Congress. Civil war had begun.

The war provoked by the South only hastened the collapse of the slave system. While initially waged by the North as a war to preserve the union, it became transformed, in the words of Lincoln, into “a remorseless revolutionary struggle,” resulting in one of the greatest and most rapid overturns of private property in history. It ended with the liberation of four million slaves, worth some $3 billion at the time, over $1 trillion dollars in today’s terms. Karl Marx wrote, “Never has such a gigantic transformation taken place so rapidly.”

The Sesquicentennial of the election of 1860 is being observed at a time when American society is perhaps more sharply polarized than at any time since the period prior to the Civil War. If anything, the blindness, greed and rapaciousness of the American and global financial aristocracy puts into the shade the old southern slavocracy.

The system of capitalist wage slavery is threatening mankind with ever-greater poverty, environmental disaster and catastrophic wars. The yoke of private ownership of the means of production is strangling the productive forces of mankind. Only the struggle for socialism by the working class offers the people of the world a way forward. To carry out this great task the working class must assimilate the lessons of history. As in 1860, only through revolutionary struggle can the working class, the vast majority of humanity, free itself from the bloody chaos of capitalism.

Notes:

(1) James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, (Oxford University Press 1988), p. 233

(2) ibid. p. 245

(3) ibid. p. 240

(4) ibid. p. 241

(5) James McPherson, The Struggle for Equality, Abolitionists and the Negro in Civil War and Reconstruction, (Princeton University Press second paperback edition 1995), p. 29

(6) ibid. p. 11

(7) James M McPherson Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution, (Oxford University press, 1991), p. 52

(8) ibid. p. 250

(9) James McPherson, The Struggle for Equality, Abolitionists and the Negro in Civil War and Reconstruction,( Princeton University Press second paperback edition), p. 26

(10) Allen C. Guelzo ,Abraham Lincoln Redeemer President,( William B Eerdmans Publishing Co, 1999), p 250

(11) ibid. p. 253

(12) ibid. p. 254

(13) ibid. p. 255

(14) James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, (Oxford University Press 1988), p. 254

(15) ibid. p. 269