The First World War (1914-1918) marked the initial foray by the US ruling elite into promoting a war with assistance from Hollywood film companies. The nation’s belated entry into the bloodbath in April 1917 was driven by the dynamic expansion of US capitalism and its increasing dependence on the global economy.

The US could no longer afford to observe from the sidelines the conflicts between the great powers, which in the first world war involved Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, on one side, and a dozen allied countries (i.e., England, France, Italy and Russia) on the other.

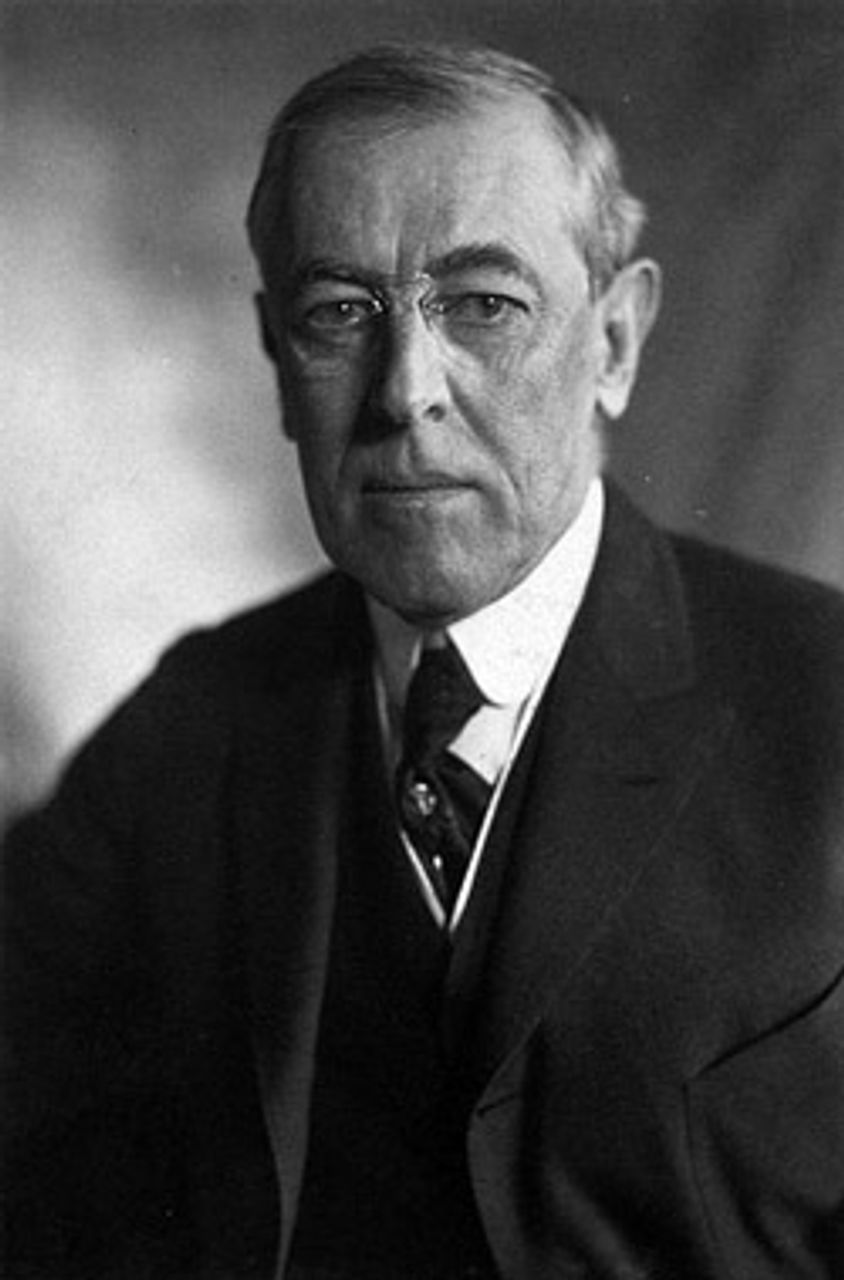

Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow WilsonThe challenge facing the Woodrow Wilson administration was selling its imperialist agenda to the general public. As historian Howard Zinn has noted, widespread popular hostility to the military action proved momentarily beneficial to left-wing elements in the socialist movement in the US who staged well-attended anti-war rallies and achieved some successes in municipal elections as a result of their opposition. But the war ultimately divided American socialists just as it did European socialists. In his 1938 affidavit for the Dies Committee (later the House Committee on Un-American Activities), for example, socialist author Upton Sinclair (producer of Sergei Eisenstein’s uncompleted ¡Que Viva Mexico!) stated he resigned from the Socialist Party in 1917 in order to declare his support for the government’s entry into World War I. [1]

Asserting the most pious and democratic motives for its military intervention was the only way the US government could garner public support for the war. The tremendous wealth, resources and economic potential still possessed by American capitalism made it possible for Wilson’s Democratic administration to preach magnanimity towards those suffering overseas. Most conveniently for Wilson, the country had in place a ready-made propaganda machine: the American film industry. What occurred during 1917-1918 (the period of US intervention) was an aggressive pro-war, film-driven public relations campaign unlike any yet undertaken. The end result was a triumph for US (and Hollywood) capitalism and a tragedy for humanity, as 320,000 American casualties were added to millions of fresh corpses around the globe.

D.W. Griffith

D.W. GriffithAt the time of the US entry into World War I, Paramount, Fox, Universal, Vitagraph (the basis for Warner Bros.) and the studios of Metro and Goldwyn (the nucleus of MGM) were already in full swing. Each company had one or more production plants, rosters of popular actors, actresses and creative personnel under contract and massive publicity/advertising/distribution apparatuses. Remarkably, artistic expression was not stifled under such conditions. Striking, lyrical achievements were in fact commonplace during the 1910s. This was the era of D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance and Lois Weber’s The Hypocrites (both 1916). It was the era of star/director Charlie Chaplin dissecting poverty and the class system in his brilliant 1917 comedy shorts Easy Street and The Immigrant. It was the decade that launched the remarkable careers of John Ford, Frank Borzage and Raoul Walsh. In the 1910s, it was still possible to make a studio film without too much front office interference.

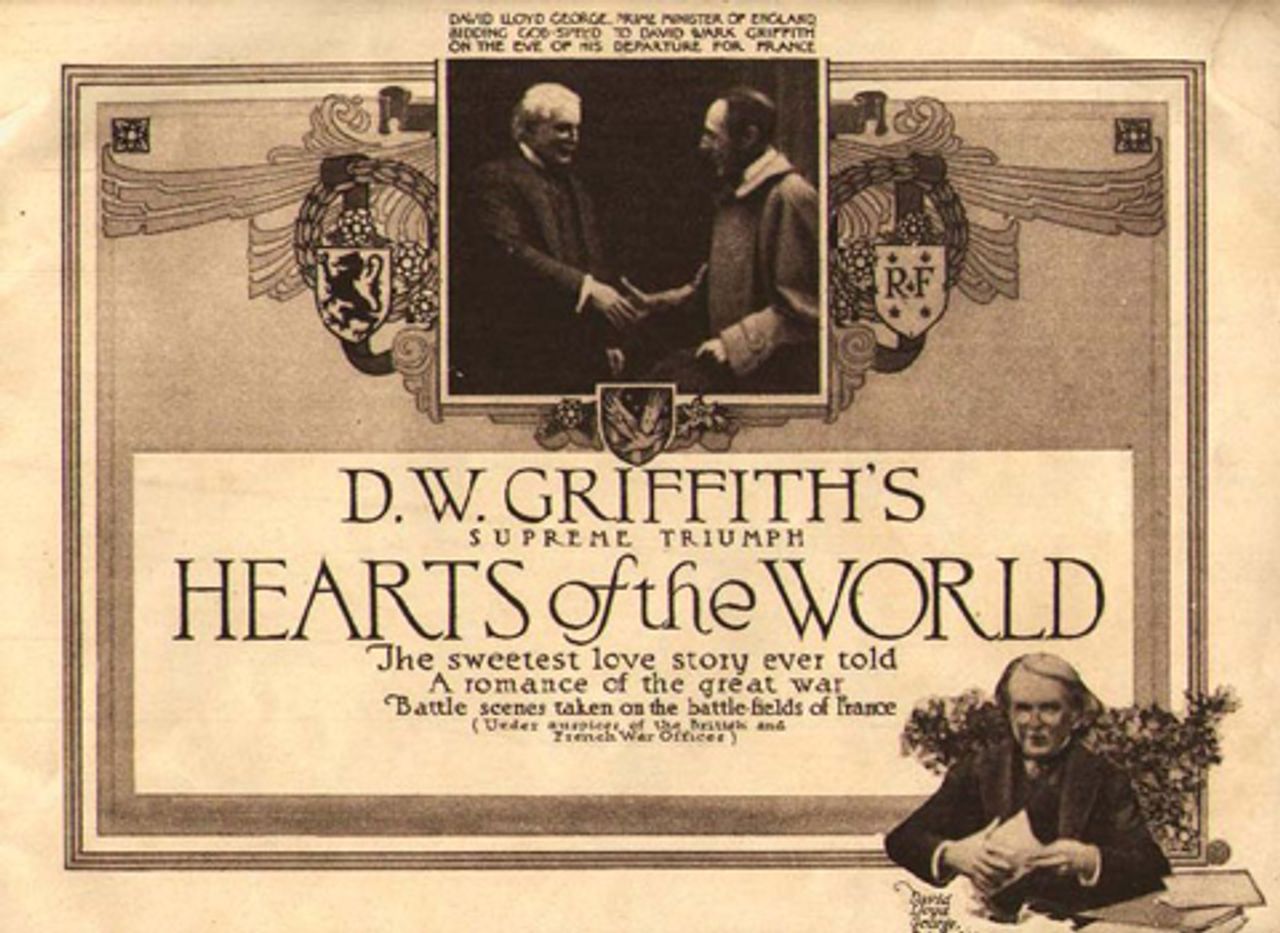

Hearts of the World (D.W. Griffith)

Hearts of the World (D.W. Griffith)That the director of the pacifist Intolerance could turn around and make the pro-war Hearts of the World two years later illustrates the political and economic pressures facing US filmmakers and their corporate subsidizers after 1916. During the first three years of World War I, the US film industry suffered losses by the closing off of certain European territories, war shortages, regulations and war-related disasters. Shrewd studio leaders understood the long-term value of the war. Unlike European film companies, the US studios enjoyed an unimpaired home market and predicted a decline in film imports as a result of the war. As German, Italian and British film production plummeted, Hollywood envisioned its own world market for the first time. [2]

1916 publicity photo for the takeover of Paramount Pictures.

1916 publicity photo for the takeover of Paramount Pictures. (L to R) Jesse L. Lasky, Adolph Zukor, Samuel Goldwyn, Cecil B.

DeMille, Al Kaufman

The first significant alliance between the US movie business and Washington, DC occurred on 27 January 1916 in New York City when President Wilson greeted a Motion Picture Board of Trade banquet audience of nearly 1,000 people. The guest list included such industry luminaries as Kodak’s George Eastman, Paramount’s Adolph Zukor and Samuel Goldfish (later Goldwyn). Toastmaster J. Stuart Blackton of Vitagraph spoke of the need for military preparation to protect US territories and recited a pro-war poem whose final words were “So fire your forges and dam the bills/For the wings of peace must have iron quills.” When Wilson addressed the audience that night, he kept his remarks limited to vague statements about truth in film storytelling. In any event, the contact between industry leaders and their chief executive gave legitimacy to the youthful US motion picture trade. [3]

Carl Laemmle

Carl LaemmleIn fairness, many of the studio chiefs felt vulnerable because they were immigrants. For the German Carl Laemmle, president of Universal Film Manufacturing Company (later Universal Pictures), these fears were justified in the fall of 1915 after several British newspapers accused Hollywood films of being backed by German capital. Laemmle moved quickly to distance himself from any German alliances by taking his lead from the Wilson administration. When neutrality was Wilson’s position in the autumn of 1914, Universal issued the two-reeler Be Neutral. When Wilson stressed preparedness, Universal offered the xenophobic 40-reel serial Liberty. In June 1916, the studio held a preparedness parade and in September of that year distributed the Lon Chaney-Dorothy Phillips war feature If My Country Should Call. [4]

Immediately after President Wilson declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, Universal announced Universal Preparedness Productions, whose offerings included serials, shorts and features with such titles as Uncle Sam at Work, The War Waif, The Birth of Patriotism and Uncle Sam’s Gun Shops. The studio scored additional propaganda points by releasing Rupert Julian’s The Kaiser, The Beast of Berlin (1918) and a satire, The Geezer of Berlin (1918). The anti-Kaiser propaganda apparently did its job well. In Davenport, Iowa, a public screening of The Beast of Berlin was interrupted when a man yelled and rushed down the aisle of the theater with a gun, firing two shots at the screen. [5]

In the fall of 1917, Universal signed its first government contract to produce official state films, starting with the US Department of Agriculture. During the summer of 1918, Laemmle’s studio produced a series of one-reelers on The Wonders of Our War Work, each of which bore “the official sanction and authority of the Committee on Public Information.” Universal lobbied newspaper support for the motion picture industry’s war activities to counteract “misguided zealots” singling out the film business as being expendable during wartime.

Universal’s Jewel production label also capitalized on the jingoistic atmosphere by filming the popular Henry Irving Dodge story The Yellow Dog and launching a “win the war” campaign in connection with chambers of commerce and various nationalistic organizations. All these pictures were still not enough for the US government. In the fall of 1918, the Department of Justice detained a shipment of Universal films to Brazil, accusing the Brazilian branch manager of “pro-Germanism” and demanding his removal (it is not known whether Universal complied). [6] With all this in mind, it is impossible not to wonder whether Laemmle’s eventual support for Lewis Milestone’s anti-war masterwork All Quiet on the Western Front (released by Universal in 1930) was not an unconscious attempt to offset some of his studio’s World War I activities.

Laemmle was only one of many moguls reaching out to the government. In early 1917, executives from Vitagraph, Famous Players-Lasky (Paramount’s official name at the time), Mutual, Fox and several trade magazines, joined Universal in sending President Wilson a telegram pledging “combined support for the defense of our country and its interests.” Reminding Wilson of Hollywood’s ability to influence the opinions of its daily 12 million US cinema patrons, the signers offered to form a commission “to place the motion picture at your service in the most intelligent and useful manner.” In July of that year, Wilson appointed William A. Brady of World Film to head the National Association of the Motion Picture Industry (NAMPI), an organization allied with the government’s Committee on Public Information. Brady assured Wilson of “the undivided conscientious and patriotic support of the entire [film] industry in America. I have the honor to be your obedient servant.” [7]

And obedient Brady and his studio colleagues were throughout the duration of US involvement in the war. “Propaganda” soon became the industry rallying cry. As the US laid battle plans, Variety reported that film companies “dealing entirely with Uncle Sam’s preparations for war” were elated over the fact that the government was planning to review films “suitable to promoting the proper propaganda” for army and navy recruiting.

Distributor Louis B. Mayer (the future head of MGM) had full charge of NAMPI’s New England war campaign and told Boston theater owners that motion pictures were “the great intermediary between the public and the government of Washington.” Widespread exhibition of films, said Mayer, provided “invaluable aid to the government and its various propagandas.” At the first rally of the Motion Picture War Relief Association in Los Angeles in May 1918, Paramount/Lasky director Cecil B. De Mille told the crowd of 2,000 that “The motion picture is the most powerful propaganda and sends a message through the camera which can’t be changed by any crafty diplomat.” [8] (This kind of comment, it should be noted in passing, gives the lie to the argument that the post-revolutionary Soviet government invented film propaganda.)

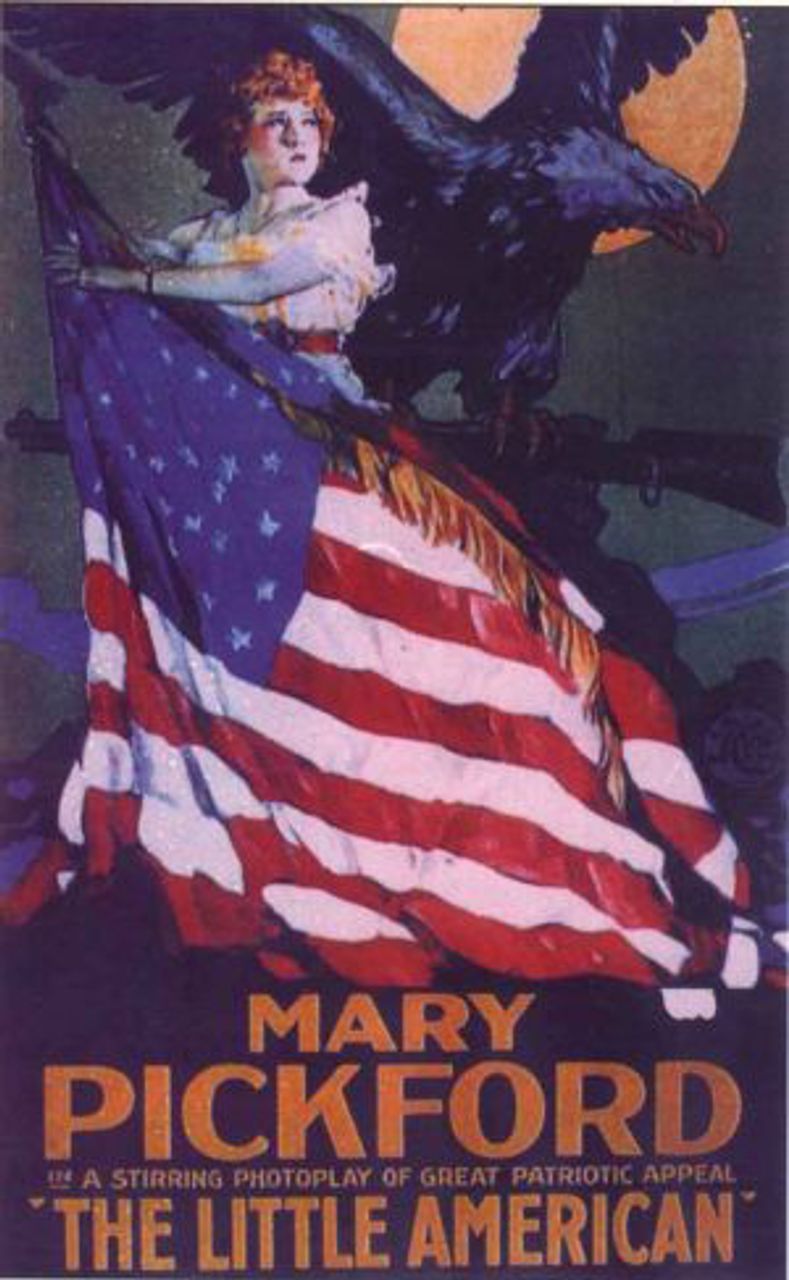

In August 1917, NAMPI assigned influential film people to government branches. Stars Mary Pickford and Anita Stewart were both appointed to the Women’s Defense Committee. Adolph Zukor and theater magnate Marcus Loew were dispatched to the Treasury Department. Exhibitor Samuel (“Roxy”) Rothapfel and the president of Metro Pictures were sent to the Department of the Interior. Mayer went to the United States Shipping Board. William Fox, Jesse Lasky, Edwin S. Porter (director of The Great Train Robbery in 1903) and Lasky star Douglas Fairbanks divided up between the East and West Coast branches of the American Red Cross. [9]

Personal appearances by stars were essential in promoting the war. In December 1917, the Canadian-born Pickford took a break in San Francisco location filming of Amarillo of Clothesline Alley to lead a Marine Corps band down Market Street, “clad in a skirted variation of a marine corps uniform.” In July 1918, the Motion Picture War Relief Association staged a parade in Los Angeles with Fairbanks as grand marshal leading 200 mounted aides. Universal director Lois Weber (Griffith’s commercial equal at the time) marshaled the women’s division of this parade that included thousands of marching men and 47 bands. Film stars Pickford, Chaplin and Fairbanks jointly addressed huge crowds in Manhattan to sell Liberty war bonds and subsequently toured the country individually. For “Liberty Day” in New York City on October 12, 1918, Zukor arranged for a traveling theater to appear on major street corners with stars from his Manhattan and Fort Lee, New Jersey film studios promoting war bonds with “a host of pretty bond sellers.” [10]

Personal appearances aside, nothing advertised government war bonds better than motion pictures. NAMPI arranged for prominent studios to produce short propaganda films touting so-called “Liberty Loans.” The Second Liberty Loan drive in the fall of 1917 was pushed by five movies featuring “leading stars and personages of stage and screen.” For the Third Liberty Loan campaign, Douglas Fairbanks starred in the short Swat the Kaiser. For the Fourth Liberty Loan drive, NAMPI chairman Zukor appeased the Treasury department by arranging for the production of 40 Liberty Loan Specials from 12 film companies and 37 stars. Among these were 100% American with Mary Pickford, Sic ‘Em, Sam with Fairbanks, The Taming of the Kaiser Bull starring Mae Murray, and Charlie Chaplin in The Bond. Hard sell pitches also came from actress Lillian Gish (dreaming of invading Germans) and comic Roscoe Arbuckle (confronting the Kaiser in Berlin). President Wilson was impressed enough by these Hollywood propaganda actions to sing the industry’s praises at the National Press Club in Washington. Several Liberty Loan films were subsequently screened in the rotunda of the US Capitol for senators, their wives and Senate employees. [11]

Political film censorship was rampant during this time. In cities with German-American populations, even pro-war movies were targeted. De Mille’s The Little American, starring Pickford, was initially banned in Chicago for its negative portrayals of German soldiers. Most censoring, however, occurred when films did not toe the official government line. In Pennsylvania, the state attorney general threatened to revoke licenses for cinemas exhibiting films that could endanger enlistment. Similar measures were discussed in New York State. In Maryland, the governor arranged with the state censor board to recall previously approved films containing any mildly anti-war sentiments or grim scenes of battlefield carnage. The Evening Sun of Baltimore praised actions to ban “maudlin pacifist and exaggerated pictures” of war. In an unusual statement, the paper went so far as to proclaim, “Any attempts to undermine and discredit the Government now are far more harmful than the sight of some lady with too abbreviated drapery capering on the screen.” [12]

This intense censorship climate was exacerbated by Wilson’s signing of the Espionage Act in June 1917, which attacked any forms of speech construed as critical of the war. Under such conditions, several film figures were arrested. French citizen Frank J. Godsell was taken into custody by the US government for showing “pro-German” films of “German militarism as an exalted institution,” according to Variety. Despite Godsell having changed the intertitles (cinema was still a silent technology in the 1910s) of the original version to downplay German propaganda; and despite his picture having screened at the National Press Club in Washington, the New York attorney general’s office seized the film. [13]

The most infamous and telling World War I film censorship case was the banning of the independent Revolutionary War picture The Spirit of ’76. Produced by Robert Goldstein (an original investor in Griffith’s 1915 pro-slavery blockbuster The Birth of a Nation), the feature became the center of government attacks after being suppressed by Chicago censors in May 1917, just a month prior to the signing of the Espionage Act. Although Goldstein regained control of the film for Los Angeles, Spirit of ’76 was soon confiscated by the Department of Justice and its producer charged with espionage. The film was deemed a threat to the British war effort due to hostile portrayals of England during the Revolutionary War, despite the overall jingoistic pro-US message. In May 1918, a shocked Goldstein received a 10-year prison sentence and a $5,000 fine (he eventually obtained an early release). [14]

Taking aim at businesses and individuals who demonstrated any “pro-German” sensibilities was part and parcel of the mood established by the Wilson administration. In late 1917, an executive at the Associated Motion Picture Advertisers introduced a resolution discouraging film companies from advertising in newspapers supportive of Germany. Half a year later, William Fox, the Hungarian cinema magnate who ran Fox Film Corp., threatened to fire any Fox employee who was not “100 percent American.” Branch managers were instructed to submit confidential reports “as to anybody whom they even suspected of not being true Americans,” stated a trade account. “These reports, Mr. Fox announced, would be thoroughly investigated, and if any employee in the Fox forces should be found to be even slightly pro-German he would be dismissed.” [15]

Such actions disturbingly foreshadow the firing and blacklisting of leftist and liberal film employees during the late 1940s and 1950s when HUAC carried out its Cold War Hollywood attacks.

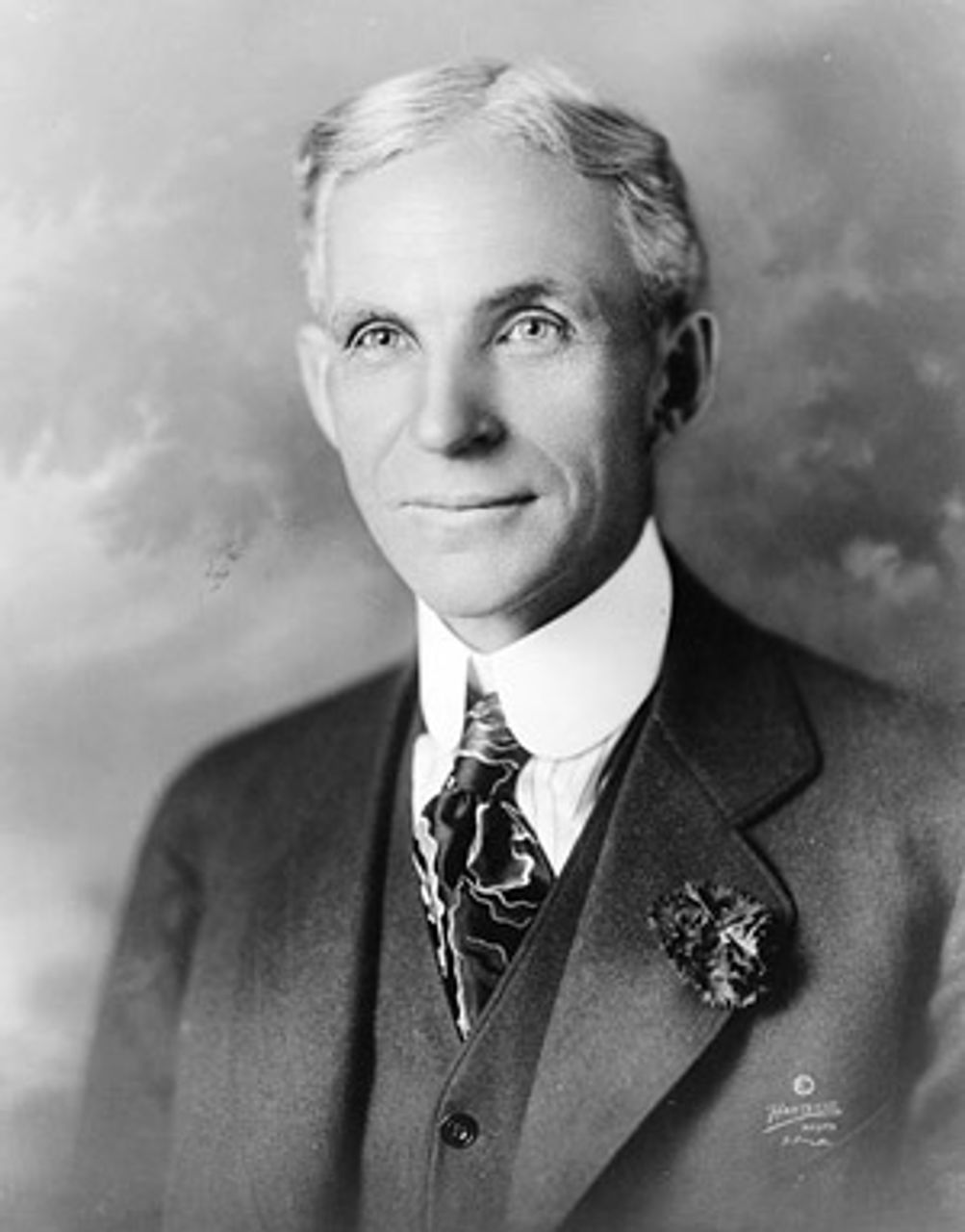

Henry Ford

Henry FordThe US government did permit political dissent of a certain type to reach cinema screens. Henry Ford, auto magnate, virulent anti-Semite and isolationist, opposed the outbreak of war for the damage he thought it would do his business operations (he later became a firm supporter of American intervention). Right up until the time the US officially declared war, it was still possible for Universal newsreel cameramen to accompany Ford’s “Peace Pilgrims” to Europe. At the dawn of 1916, the French-owned Pathé Exchange even distributed an anti-war three-reeler called The Horrors of War, which future war profiteer Ford publicly endorsed. One very short and momentous year later, no US film producer would have dared issue such a picture to theaters for fear of political reprisals. Pro-war studio-distributed newsreels and government films soon replaced the “horrors of war” documentary. [16]

In a similar vein, Liberty Loan public and film appearances did not dissuade Charlie Chaplin from making his satirical Shoulder Arms, released shortly before the 1918 Armistice. The increasingly inflamed atmosphere of “anti-red” paranoia also failed to dissuade Triangle Film Corp. from presenting a feature sympathetic to socialism called The Answer (1918)—five months after the Russian Revolution. These, however, were exceptions in an intensely reactionary atmosphere.

The beleaguered public of the World War I years could not be fooled for long. As soon as the war came to an end, the pro-war cult collapsed. Hollywood writers and directors were equally scarred by the impact of the devastating war and responded with artistic rage. Only 27 months after the Armistice, Metro Pictures released Rex Ingram’s harrowing masterpiece The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921). That such a downbeat pacifist drama could go on to become a huge success is a testament to public backlash against the government’s 1917-1918 propaganda campaign. Hostility towards the war continued through the Great Depression years and studios responded with such remarkable anti-war dramas as King Vidor’s The Big Parade (MGM 1925) and Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front.

This all too brief period of humanistic reflection on imperialist warfare regrettably gave way to more intense rounds of Hollywood’s political capitulation. There was a high price to pay for such capitulation. Film industry support for US government actions during World War II surpassed anything Hollywood had done during 1917 and 1918. After that war ended in 1945, the government showed its gratitude by carrying out, with studio cooperation, “anticommunist” purges from which US filmmaking has yet to recover.

Film is a powerful medium, but nowhere in the world is it so much a private preserve of commercial interests as in the US. As the social crisis develops and the working class comes forward, these interests will once again fiercely exert their social priorities and demands. In both world wars, the Depression and the witch-hunt era, the studio heads demonstrated their devotion to US capitalism.

At the same time, of course, there are countless writers, actors, directors and even producers who are critical of American society and who could be won to opposing it. A knowledge of this history is vital to them, too.

Notes:

[1] Zinn, Howard, A People’s History of the United States (Harper & Row, 1980), pp. 355-56. Bentley, Eric, editor, Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts from Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938-1968 (New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press/Nation Books, 1971, 2002), p. 48.

[2] “The War’s Effect on the Movies,” The Billboard (19 December 1914), p. 153.

[3] Bush, W. Stephen, “Motion Picture Men Greet President,” Moving Picture World (12 February 1916), pps. 923+. “First Board of Trade Banquet, Attended by President Wilson, Marks New Era in Industry,” Motion Picture News (12 February 1916), pp. 817-18.

[4] Variety (20 August 1915), p. 17. “Universal Backs Wilson on Neutrality”, Motion Picture News (19 September 1914), p. 57. The Billboard (19 September 1914), p. 46. Moving Picture World (22 July 1916), p. 644. Motion Picture News (12 August 1916), p. 927. Universal advertisement, ibid, pp. 928-29. Moving Picture World (9 September 1916), p. 1629.

[5] Universal advertisement, Moving Picture World (5 May 1917), p. 706. Ibid, p. 810. Universal advertisement, ibid, p. 820. Moving Picture World (3 August 1918), p. 703. “Shot ‘Beast of Berlin,’” Variety (12 April 1918), p. 47.

[6] “Universal Gets Government Contract,” Moving Picture World (15 September 1917), p. 1774. “Universal Puts Out Stirring Training Film,” Moving Picture World (4 May 1918). “Universal to Make Films for Government,” Moving Picture World (22 June 1918), p. 1724. “Universal Appeals to Newspapers,” Moving Picture World (29 June 1918), p. 1850. “Roosevelt Backs Anti-Yellow Dogism,” Moving Picture World (17 August 1918), p. 992. “Jewel’s Anti-Yellow Dog Campaign Is Spreading Fast,” Moving Picture World (24 August 1918), p. 1137. Variety (13 September 1918), p. 49. Variety (20 September 1918), p. 49.

[7] “President Wilson Offered Aid of Film Men,” Motion Picture News (24 February 1917), p. 1197. “President Wilson Calls Upon Film Industry,” Moving Picture World (14 July 1917), p. 217.

[8] “Gov’t to Look at Films,” Variety (4 May 1917), p. 16. “War Work Under Way in Boston,” Moving Picture World (1 September 1917), p. 1350. “Industry in West to Black the Government,” Moving Picture World (15 June 1918), pp. 1549-50.

[9] “Motion Pictures Mobilized for War,” Moving Picture World (11 August 1917), p. 918.

[10] “Mary Pickford Leads Parade,” Moving Picture World (5 January 1918), p. 127.

Variety (16 August 1918), p. 40. “Industry in West to Black the Government,” Moving Picture World (15 June 1918), pp. 1549-50. “Industry to Back Liberty Loan,” Moving Picture World (9 June 1917), p. 1617. “Industry’s Drive Under Full Speed,” Moving Picture World (19 October 1918), p. 352. “Motion Picture Industry Boosting Bond Sale,” Moving Picture World (4 May 1918), pp. 672-74. “Public Responds to Players’ Appeals,” Moving Picture World (18 May 1918), p. 972.

[11] NAMPI advertisement, Variety (12 October 1917), pps. 36-37. “Five Hundred Prints for Liberty Film,” Moving Picture World (13 October 1917), p. 209. “Zukor Committee Announces Plan for Loan Drive,” Moving Picture World (3 August 1918), p. 665. “Liberty Loan Distribution Arranged for Special Films,” Variety (30 August 1918), p. 41. “Synopses of Liberty Loan Specials,” Moving Picture World (5 October 1918), p. 122. “Great Array of Star Films to Boom Liberty Loan Drive,” Variety (20 September 1918), p. 49. “Fifty Stars Contribute to Loan,” Moving Picture World (7 September 1918), p. 1407. “Industry’s Drive Under Full Speed,” Moving Picture World (19 October 1918), pp. 351-52. NAMPI advertisement, Variety (27 September 1918), pp. 44-45.

[12] “That Chicago Censor,” Variety (6 July 1917), p. 17. “Bans All Films That Discourage Enlisting,” Moving Picture World (5 May 1917), p. 832. “Shall Horrors of War in Film be Banned?” Moving Picture World (5 May 1917), p. 834. “Maryland Censors Recall Certain War Films,” Moving Picture World (12 May 1917), p. 997.

[13] “Juggling Propaganda,” Variety (22 March 1918), p. 57.

[14] AFI Catalogue of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States; Feature Films, 1911-1920 (Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1988), p. 875.

[15] “Pro-German Papers Cut Off,” Variety (2 November 1917), p. 53. “William Fox Will Dismiss Pro-Germans,” Moving Picture World (29 June 1918), p. 1859. “What William Fox Is Doing to Help Win the War,” Moving Picture World (21 September 1918), p. 1745. “How Fox Organized the War Drive,” Moving Picture World (30 November 1918), pp. 923-24.

[16] Moving Picture World (26 February 1916), p. 1273. Pathé advertisement, Moving Picture World (8 January 1916), pps. 192-193, quoting Ford in 3 December 1915 New York Journal. “Patriotism Pervades Hearst-Pathe News,” Moving Picture World (17 April 1917), p. 2921. “Triangle to Distribute ‘Booster’ Picture,” Moving Picture World 27 (October 1917), p. 509.