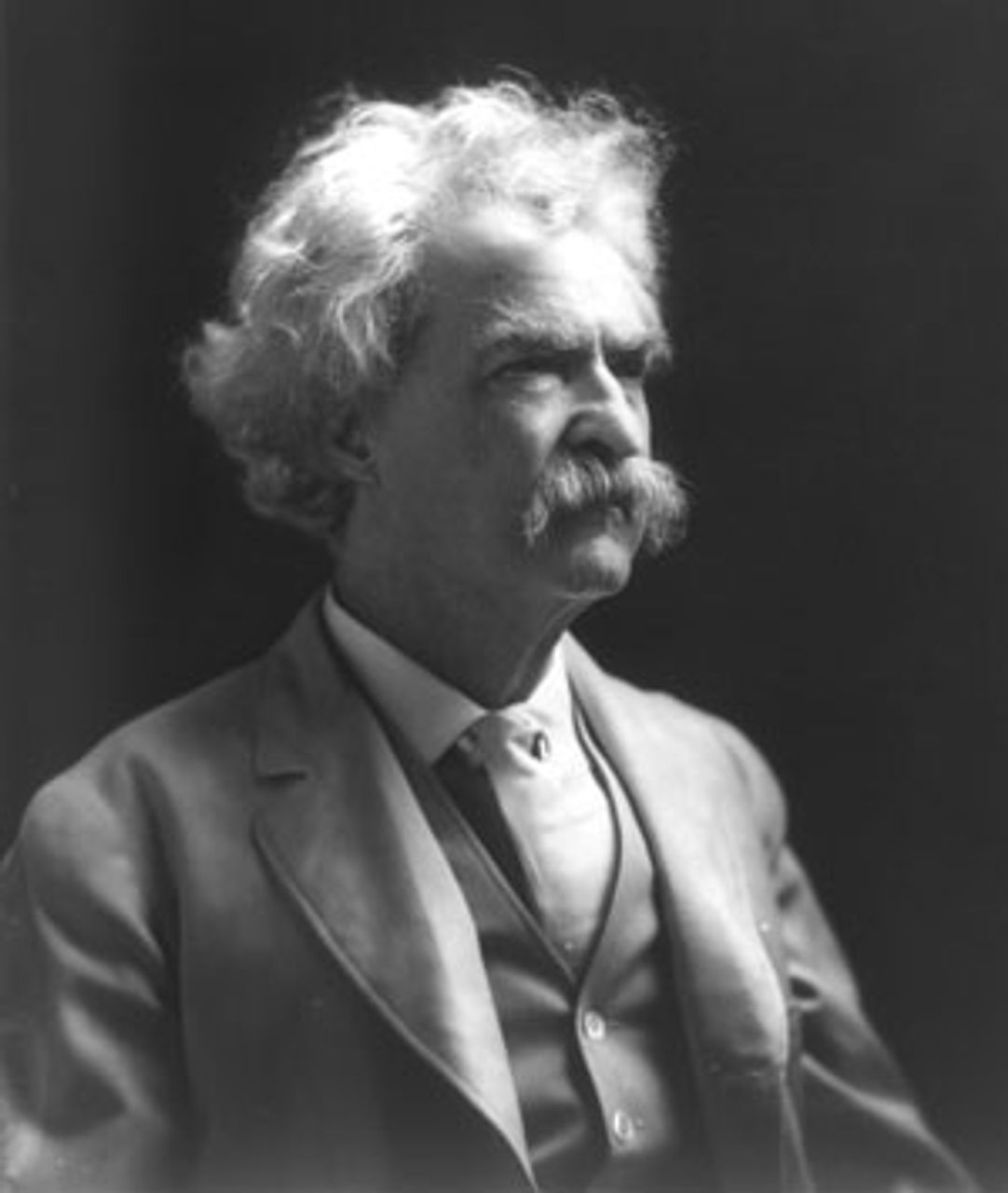

April 21 marked 100 years since the death of Mark Twain, one of the greatest American writers in history. Twain (1835-1910) was a brilliant satirist, a comic genius, and a master at capturing the sound and rhythm of American vernacular in so many of its nineteenth century varieties.

It is not possible in a single, relatively brief article to examine Twain’s life and writings in the manner they deserve. This is an enormous subject, full of complexities and contradictions. During his lifetime, the writer experienced great acclaim and success, along with financial bankruptcy and bouts of terrible personal tragedy.

One of the great comic writers of all time, one of the few who provoke the reader to laugh out loud, “what burned in him,” suggested the editor of his papers, Bernard De Voto, “was a hatred of cruelty and injustice,” as well as a “deep sense of human evil, and a recurrent accusation of himself. Like Swift he found himself despising man while loving Tom, Dick, and Harry so warmly that he had no proper defense against the anguish of human relations.”

Twain’s life spanned a remarkable period. He was born only 50 years after the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War—when many veterans of the independence struggle were still alive—in Missouri, at the time still frontier territory. Twain lived to see the US undergo a bitter Civil War, develop its industrial might and emerge full-blown as an imperialist power on the eve of World War I.

Whether restless by nature or necessity, Twain experienced every part of the country and encountered every social type early in life. De Voto noted that the author, in his formative years, “had seen more of the United States, met more kinds and castes and conditions of Americans, observed the American in more occupations and moods and tempers—in a word had intimately shared a greater variety of the characteristic experiences of his countrymen—than any other major American writer.”

Born Samuel Langhorne Clemens in Missouri in 1835, Clemens worked as a printer, journalist, and steamboat pilot on the Mississippi before gaining widespread recognition as a writer of travel letters, first on his trip to Hawaii (then known as the Sandwich Islands) in 1866 and then to Europe, North Africa and the Middle East a year later.

The material from the latter trip was turned into The Innocents Abroad in 1869. This work made Twain—he had already adopted his famous pen name while working at a Nevada newspaper in 1863—both critically and financially successful. The book sold 85,000 copies in its first 16 months.

An aphorism from the conclusion of the text shows that Twain had already developed his socially acute sense of humor: “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely on these accounts.”

Two critics comment that Twain’s own move East to New York City in 1866 “signaled the start of his remarkable synthesis of the elements of post-Civil War American writing as he undertook to link the local-color and Western tradition of his early work with the social, intellectual, commercial and industrial spirit of the decades he himself helped name the Gilded Age.” (From Puritanism to Postmodernism: A History of American Literature, Richard Buland and Malcolm Bradbury)

In his first novel, entitled The Gilded Age (1873), Twain (and co-author Charles Dudley Warner) looked at the period 1860-1868 as one that, in their own words, “uprooted institutions that were centuries old, changed the politics of a people, transformed the social life of half the country, and wrought so profoundly upon the entire national character that the influence cannot be measured short of two or three generations.” In sum, a revolution had taken place, which had an enormous subsequent influence on artistic and intellectual life.

Twain produced his greatest works between the early 1870s and 1890. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) clearly rank among them. Both works defy easy categorization: they offer comic scenes that generate tears of laughter interspersed with passages, for example, that depict the brutality of slavery as it existed in the antebellum South of Clemens’s childhood (and other disturbing facets of American life of the time).

Briefly in the Confederate ranks in the Civil War, Twain unquestionably accumulated a deep antipathy for slavery. “A True Story,” a remarkable short story published in 1874, is told from the point of view of a black woman, a former slave. “Aunt Rachel,” now a servant, informed by her complacent employer that she seems to have lived 60 years and “never had any trouble,” turns on him and recounts how, in fact, she was separated from her husband and children by a slave auction, and only united with one of her sons after 22 years. Novelist and editor William Dean Howells, who published it in the Atlantic, told Twain that he thought the story “extremely good and touching and with the best and reallest kind of black talk in it.” (Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain, Justin Kaplan)

In Huckleberry Finn, one of the great achievements of nineteenth century American literature, the young title character (and narrator) recounts his adventures on the Mississippi River in the company of Jim, an escaping slave who is trying to get to a free state so he can buy his family’s freedom.

Throughout the book, Huck’s conscience is bothered by the fact that he is “stealing” someone’s property in helping Jim escape. At one point, he determines to turn the slave in, and writes a note to his old owner. The novel continues:

“I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time I had ever felt so in my life, and I knowed I could pray now. But I didn’t do it straight off, but laid the paper down and set there thinking—thinking how good it was all this happened so, and how near I come to being lost and going to hell. And went on thinking. And got to thinking over our trip down the river; and I see Jim before me all the time: in the day and in the night-time, sometimes moonlight, sometimes storms, and we a-floating along, talking and singing and laughing. But somehow I couldn’t seem to strike no places to harden me against him, but only the other kind. I’d see him standing my watch on top of his’n, ‘stead of calling me, so I could go on sleeping; and see him how glad he was when I come back out of the fog; and when I come to him again in the swamp, up there where the feud was; and such-like times; and would always call me honey, and pet me and do everything he could think of for me, and how good he always was; and at last I struck the time I saved him by telling the men we had small-pox aboard, and he was so grateful, and said I was the best friend old Jim ever had in the world, and the ONLY one he’s got now; and then I happened to look around and see that paper.

“It was a close place. I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a-trembling, because I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

“ ‘All right, then, I’ll GO to hell’—and tore it up.”

The profound humanity and sympathy of this passage hardly need to be emphasized.

Ernest Hemingway famously asserted that “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” Critic and commentator H.L Mencken suggested that the novel was “one of the great masterpieces of the world” and would “be read by human beings of all ages, not as a solemn duty but for the honest love of it, and over and over again.” Mencken, himself often consumed with misanthropy, noted that Twain in his writing laughed at people, “but not often with malice. What genuine indignation he was capable of was leveled at life itself and not its victims.”

Another fascinating work from this period is Life on the Mississippi (1883), a mostly non-fiction account, which Twain wrote in tandem with Huckleberry Finn. Life on the Mississippi cost its author great effort. “I never had such a fight over a book in my life before,” he wrote Howells in 1882. But the result is a beautifully written book, a detailed and emotionally intense account of life as a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi River in the years immediately prior to the Civil War.

The following passage may help explain why Twain poured such a depth of feeling into the book: “In my preceding chapters I have tried, by going into the minutiae of the science of piloting, to carry the reader step by step to a comprehension of what the science consists of; and at the same time I have tried to show him that it is a very curious and wonderful science, too, and very worthy of his attention. If I have seemed to love my subject, it is no surprising thing, for I loved the profession far better than any I have followed since, and I took a measureless pride in it. The reason is plain: a pilot, in those days, was the only unfettered and entirely independent human being that lived in the earth. Kings are but the hampered servants of parliament and people; parliaments sit in chains forged by their constituency; the editor of a newspaper cannot be independent, but must work with one hand tied behind him by party and patrons, and be content to utter only half or two-thirds of his mind; no clergyman is a free man and may speak the whole truth, regardless of his parish’s opinions; writers of all kinds are manacled servants of the public. We write frankly and fearlessly, but then we ‘modify’ before we print. In truth, every man and woman and child has a master, and worries and frets in servitude; but in the day I write of, the Mississippi pilot had none.”

The darker aspects of American life treated in Huckleberry Finn are even more pronounced in the less celebrated, but also remarkable, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889) and Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894). The latter contains one of Twain’s few fully realized female characters, the light-skinned slave Roxana, so desperate to keep her child from being sold that she switches him in the cradle for her master’s child.

The former novel, about a nineteenth century American, Hank Morgan, a resident of Hartford, Connecticut (where Twain had set up residence), who finds himself transported back in time to medieval England at the time of King Arthur and his knights, was initially conceived of in 1884 as relatively light-hearted.

However, Justin Kaplan, in his biography of Twain, contends, “[O]ver the years this comic idea changed its course and headed away from burlesque and toward an apocalyptic conclusion in which chivalric England and Hank Morgan’s American technology—failures both, as the author had come to see them—destroy each other.”

Twain wrote The United States of Lyncherdom, a significant essay published posthumously (in 1923), in outrage over the 1901 lynching of three black men in Pierce City, Missouri. In the piece, the author counters the claim that the people constituting the lynch mob approved and enjoyed the torturous killings. Rather, the crowds acquiesced for fear of scorn by their peers. In a plaintive suggestion to end these killings—then totaling more than a hundred per year in the US—Twain wrote: “[P]erhaps the remedy for lynchings comes to this: station a brave man in each affected community to encourage, support, and bring to light the deep disapproval of lynching hidden in the secret places of its heart—for it is there, beyond question.”

Throughout his adult life, Twain was scathing about American political life and its practitioners. Who could look on the self-important and thieving corporate toadies collectively known as the US Congress with the same eyes after a dose of Twain’s wit? For example, he once noted, “Suppose you were an idiot. And suppose you were a member of Congress. But I repeat myself.” In What is Man? the novelist observed that “Fleas can be taught nearly anything that a Congressman can.” A personal favorite: “It could probably be shown by facts and figures that there is no distinctly native American criminal class except Congress.”

Several significant episodes in Twain’s life have received relatively scant attention in tributes this week. One of these is Twain’s critical role in the publication of the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. Grant had been the US Civil War general most responsible for the military defeat of the Southern slavocracy, and later became US president. The memoirs, with their singular political and literary value, would not likely have seen the light of day without Twain publishing them himself. And he did so with considerable generosity towards their author. Grant finished the memoirs five days before his death in 1885. Twain awarded 75 percent of the proceeds to Grant’s estate, allowing his widow to escape the poverty in which Grant had been left after being swindled out of the last of his money.

Another fascinating episode in Twain’s life was his sojourn in Vienna from September 1897 to May 1899. It is not possible to do justice here to this period in the author’s life (which is the subject of an excellent book, Our Famous Guest: Mark Twain in Vienna by Carl Dolmetsch). But it should be briefly noted that from Vienna, Twain wrote articles for the American press denouncing the anti-Semitism of the ruling party and articulating a warm sympathy for and appreciation of the Jews who were the subject of widespread persecution.

Twain had no shortage of personal tragedy, which, one suspects, helped shape his literary and personal sympathies. Three of Twain’s six siblings died in childhood. One of those who survived, his brother Henry, died in riverboat accident in 1858 while only 19 years old. Much later, in 1872, Twain was to lose his year-old son Langdon to diphtheria, an event for which he largely blamed himself. One of his three daughters, Susy Clemens, died of meningitis in 1896. His wife, Olivia, 10 years his junior and to whom Twain was very devoted, died in 1904. His youngest daughter, Jean, died on Christmas Eve, 1909. Jean’s death followed by only seven months that of his close friend, the oil baron Henry Rogers.

Rogers had been instrumental in helping Twain extricate himself from financial ruin in 1893. Following his declaration of bankruptcy, Twain undertook a worldwide lecture tour to repay his debtors. Approaching his seventh decade and under no legal obligation to do so, Twain undertook considerable efforts to pay back his creditors in full.

If there is a misanthropic vein in Twain’s humor, especially his later humor, it should be seen in the context of these personal difficulties and tragedies, as well as his growing disillusionment with the political and social trajectory of the United States.

Believing initially in the mission of the US government to “spread democracy,” Twain first supported American military intervention in the Philippines during the Spanish-American war. By 1901, however, Twain wrote that he had changed his view diametrically and concluded that the whole campaign had been waged “to conquer, not to redeem.” He went on to become the vice-president of the American Anti-Imperialist League.

Most media treatments of Twain’s life and career shy away from his increasingly critical and radical pronouncements on American society and political life toward the end of his life. Twain had witnessed the transformation of the young American bourgeois democracy into a modern power. Revolted by US imperialism at its birth, Twain became an outspoken critic. The bourgeois press of today does not wish to be reminded, nor to remind anyone else, of this critical element of Twain’s life.

A longtime champion of the early trade union movement, the Knights of Labor, and a foe of anti-Chinese immigration, Twain had reached quite radical conclusions by the late 1880s. Kaplan writes “that he was passing through some crisis of ebbing faith in the Great Century ...‘The change ... is in me.’” he wrote to Howells. “When he said this in August 1887, he had just been rereading Carlyle’s French Revolution, and he recognized that ‘life and environment’ had made him ‘a Sansculotte! [working class radicals of the French Revolution of 1789]—And not a pale, characterless Sansculotte, but a Marat’—calling for death to all ancient forms of authority: monarchy, aristocracy, the Catholic Church.”

The media is similarly reticent today in regard to Twain’s anti-religious writings.

Initially inclined towards a form of deism, Twain essentially rejected all organized religion and subjected religious conceptions to withering criticisms, especially in his later work. Even his relatively early writings like Innocents Abroad and Tom Sawyer take a fairly irreverent and humorous view of theological matters. But his later writings, especially Letters from Earth (written in 1909, but not published until 1962 owing to his surviving daughter’s apprehension), take a bold and combative turn. In the Letters, Twain has Satan describe with great amusement the self-satisfaction of mankind who “thinks he is the Creator’s pet” even though the reality is that, “[w]hen he is at his very very best he is a sort of low grade nickel-plated angel; at is worst he is unspeakable, unimaginable….”

God is not spared any criticism here either. “Will you examine the Deity’s morals and disposition and conduct a little further? And will you remember that in the Sunday school the little children are urged to…make him their model and try to be as like him as they can?” Twain then lists Biblical injunctions for the ancient Israelites to exterminate the inhabitants of the “Promised Land.” With such a model for moral teaching, Twain says, it is no wonder that society perpetuates violent human conflict. It was Twain’s revulsion at such conflict, particularly in its brutal colonial forms, that impelled him to attack the religious conceptions that defended or apologized for it.

In the closing sentence of My Mark Twain, his friend, critic and fellow author William Dean Howells said famously: “Emerson, Longfellow, Lowell, Holmes—I knew them all and all the rest of our sages, poets, seers, critics, humorists; they were like one another and like other literary men; but Clemens was sole, incomparable, the Lincoln of our literature.” With this statement we can certainly agree.

No less true, although less often cited, is the preceding sentence in which Howells described Twain’s appearance at the funeral: “I looked a moment at the face I knew so well; and it was patient with the patience I had so often seen in it; something of the puzzle, a great silent dignity, an assent to what must be from the depths of a nature whose tragical seriousness broke in the laughter which the unwise took for the whole of him.” How fitting are these words that point to the complexity of the great author.

When considering Mark Twain a hundred years after the fact, one cannot help wondering what he would have to say about the America of 2010. One can only imagine his shock and dismay at the way in which the malignant social and political tendencies that he had observed in their relative infancy had metastasized.

What an abundance of targets present themselves! The well-heeled hypocrites and liars in the White House and Congress, the relentlessly avaricious corporate aristocrats, the patriotic editors justifying a resurgence of colonialism, the millionaire preachers with their put-on piety, the fake, smiling face of television anchors, the charlatanry of the “self-help” experts and all the other fleecers of the population’s pockets—all of it ripe for, in Twain’s phrase, “a pen warmed up in hell”! Where are his heirs today?

See also:

Ken Burns’ Mark Twain: a not quite unflinching portrait

[9 February 2002]