María Isabel Vásquez Jiménez

María Isabel Vásquez JiménezThree company officials, who managed a now defunct farm labor-contracting firm in California’s agricultural Central Valley, were charged April 24 with involuntary manslaughter in the death of 17 year- old María Isabel Vásquez Jiménez on May 16 of last year.

The young woman died on May 16, 2008 of a heat stroke as she worked in a vineyard in triple-digit temperatures. The California occupational safety agency issued a heat warning that day to all employers. Ms. Vásquez Jiménez was two months pregnant at the time.

San Joaquin District Attorney James Willet filed charges against the former owners of Merced Farm Labor, which the state shut down after Jiménez’s death last year. A state investigation concluded that she and other workers had been denied adequate shade and water and that these factors had contributed to her collapse under the oppressive heat.

The former owner of the company, María de Los Ángeles Colunga, its former safety director, Elías Armenta, and ex-supervisor Raúl Martínez have all been charged with a felony and five counts of misdemeanor for failure to provide portable water, adequate shade, heat illness training, and prompt medical care. If convicted, they could face two to five years in prison.

Raúl Martínez failed to appear in court Tuesday, and is believed to have fled to Mexico. The district attorney’s office is filing a warrant for his arrest.

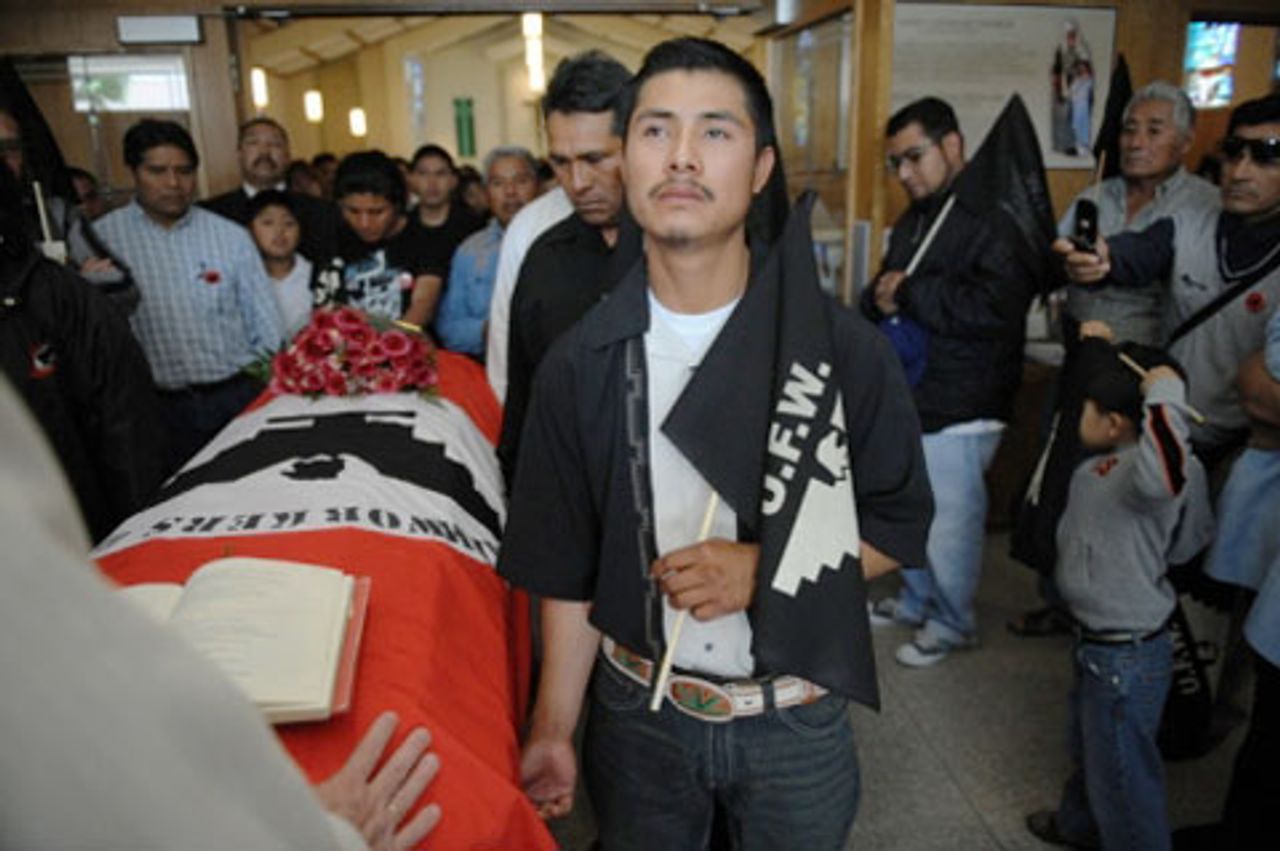

Jose Luis Vasquez touches the casket of his sister during a service following her death last year CREDIT: Hector Amezcua www.dominionpaper.ca

Jose Luis Vasquez touches the casket of his sister during a service following her death last year CREDIT: Hector Amezcua www.dominionpaper.caDoroteo Jiménez, the girl’s uncle, commented on the charges against the three to Recordnet.com, “In reality, I thought they weren’t taking it seriously. This is something that gives us a little hope,” he said. “At least, justice is being served.”

The death of Jiménez, a teenager, speaks volumes about the horrible conditions of life facing millions of undocumented migrants in the United States. Her background was fairly typical. A native of Oaxaca, Mexico, she came to the United States last year to join her fiancé, Flaurentino Bautista, and worked and lived in California’s agricultural San Joaquin basin in order to help her widowed mother back home. The couple planned to marry and return to Mexico in three years. Bautista, 19, had saved up money to buy his childhood sweetheart a gold ring.

Both found work pruning grapes for a vineyard located near Stockton. It was owned by West Coast Grape Farming, Inc., which contracted Merced Farm Labor for workers, and is a division of Bronco Wine Co., a multimillion-dollar business owned by Franzia Wines.

The piece-rate pay system under which these super-exploited workers operate is a source of life-and-death pressure under conditions of extreme heat. To take breaks for drinking water means slowing down and earning less money. As construction jobs keep dwindling due to the recession, competition has increased for work in agricultural fields. This means workers are now less likely to complain about the wretched working conditions for fear of losing their jobs.

According to California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation, farm work is one of the most dangerous occupations in the US. In 1996, the death rate among agricultural workers nationwide was estimated at 20.9 per 100,000 workers, compared to the average of 3.9 per 100,000 for all industries.

In May 20, 2001, an article from the Sacramento Bee entitled “California Farm Labor by the numbers” reported that between 1996 and 1999, there was a 33 percent increase in deaths among California farm workers. During this same time, the state experienced a 9 percent decrease in industrial fatalities.

The day María Jiménez collapsed she had only been on the job for three days and was working a 9.5-hour shift, beginning at 6:00 a.m., for $8 an hour. This was more than four hours over the state limit for minors working during business days.

Bautista said that the workers were only given one water break at 10:30 a.m. The drinking water was 10 minutes away, which took time away from working. Supervisors grumbled whenever workers would ask for water breaks. No one offered Jiménez water or shade, and no attempt was made to call emergency medics. Jimenez collapsed at 3:30 p.m. and for at least five minutes all the supervisor did was stare at her as

Bautista cradled her, according to her fiancé.

“When she fell, she looked bad,” Bautista told NPR.com, “She didn’t regain consciousness. She just fell down and didn’t react. I told her to be strong so we could see each other again.”

After she collapsed, her supervisor told her fiancé to lay her down in the bed of a hot van and put a wet cloth on her forehead. The supervisor did not call emergency care, but released her to Bautista. An employee then drove her to a nearby market and tried to revive her with rubbing alcohol before taking her to the nearby clinic in Lodi two hours later. The clinic staff rushed her to a hospital where doctors later discovered she was two months pregnant.

Bautista said that neither he nor Maria was given safety training as mandated by state law. He also said that his supervisors had told him to lie. “The foreman told me to say that she wasn’t working for a contractor, that she got sick while exercising,” Bautista related in Spanish. “He said she was underage, and it would cause a lot of problems.” Two days later, she died from heat illness. The county coroner said her core temperature had reached 108 degrees.

Last week District Attorney Willet also filed a lawsuit against West Coast Grape Farming Inc., stating that the company did not provide state-mandated training on heat sickness prevention. The lawsuit seeks $500,000 in civil penalties from the company, Merced Farm Labor, and María de Los Ángeles Colunga.

Last year, the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA) also levied a fine of $262,700 against Merced Farm Labor for violating eight workplace safety rules. It was the largest fine ever issued to a California farm contractor. The company’s license was suspended shortly afterwards. There has yet to be a follow-up inspection; there are only 200 inspectors for millions of California employers.

A 2005 law requires employers to provide each worker with four cups of water every hour, shaded resting areas, paid breaks of at least five minutes, safety training and emergency plans.

Despite the law however, in 2008 Cal/OSHA officials issued 1,122 citations for violations of the state’s heat illness prevention laws—almost double the number issued in 2007. In 2008, state officials fined farm contractors more than $3.9 million in penalties.

However, many companies were only mandated to pay a few hundred dollars in fines, even in cases where an employee died. So far, only $787, 983 has been collected. The biggest problem Cal/OSHA attorneys face in holding employers accountable is the disappearance of witnesses, as well as their refusal to testify in court.

Meanwhile the testimonies of farm workers on company violations are considered hearsay and inadmissible in court.

For his part, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger has vetoed three times a bill that would have made it easier for farm workers to unionize. The bill would have allowed them to submit a petition signed by the majority of the employees to the State Agricultural Labor Relations Board. Once the board verified the voting cards, they could form a union.

Doroteo Jiménez, María Jiménez’s uncle, has since become active in pushing for the bill. But he was fired by Merced Farm Labor after Maria’s mother filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the company last summer. Even though he asked for permission to miss work, Jimenez said his supervisors fired him for missing a “safety training” exercise. This was in all likelihood an act of retaliation because of the lawsuit; he was fired the same day.

Bautista told Recordnet.com “She (Maria) died of dehydration before we got to spend any time with her. I feel very badly because she’s my family.”

Moreover, the death of Vásquez Jiménez was only the first of many Californian farm workers to succumb to heat exhaustion. A total of 15 farm workers have died from it since Gov. Schwarzenegger took office in 2005.

The most recent heat-related death occurred last August, when María de Jesús Álvarez, 63 and the mother of nine, died while picking grapes for Anthony Vineyards on July 15. She had collapsed after suffering from dehydration and heat stroke. According to witnesses, the crew of 150 workers had received no training for heat illness prevention. According to weather.com, the temperature reached a high of 111F (44C) that day. After being treated at two different hospitals, she died on August 2, 2008.

Arturo Rodriguez, the president of the United Farm Workers, led a 40-mile protest march from Lodi to Sacramento to protest the death of María Isabel Vásquez Jiménez. He told npr.com, “The life of a farm worker isn’t important to people. People just don’t care.... The reality is that the machinery of growers is taken better care of than the lives of farm workers. You wouldn’t take a machine out into the field without putting oil in it. How can you take the life of a person and not even give them the basics?”

Subscribe to the IWA-RFC Newsletter

Get email updates on workers’ struggles and a global perspective from the International Workers Alliance of Rank-and-File Committees.