Fatality estimates continued to rise Monday in Petionville, Haiti, as rescue workers searched through the rubble for survivors three days after a school collapsed on hundreds of children.

As of this writing, authorities have announced at least 94 deaths, with at least 150 more severely injured, and the likelihood of further upward estimates as excavation proceeds.

Around 700 students were enrolled at the school, although no estimates of Friday’s attendance have been released. According to statements by rescuers, no signs of life have been detected since four children were saved on Saturday morning.

The tragedy has further strained the tense social and political situation in the country. The British Guardian reported that many residents suspected rescuers of working especially slowly in order to collect more wages.

Press reports Monday related that about 100 residents, frustrated and angry over the slow pace of rescue efforts, rushed over police barricades into the rubble and began tearing away debris with their hands. The Associated Press noted, “Thousands of onlookers cheered them before Haitian police and UN peacekeepers drove them back with batons and riot shields.”

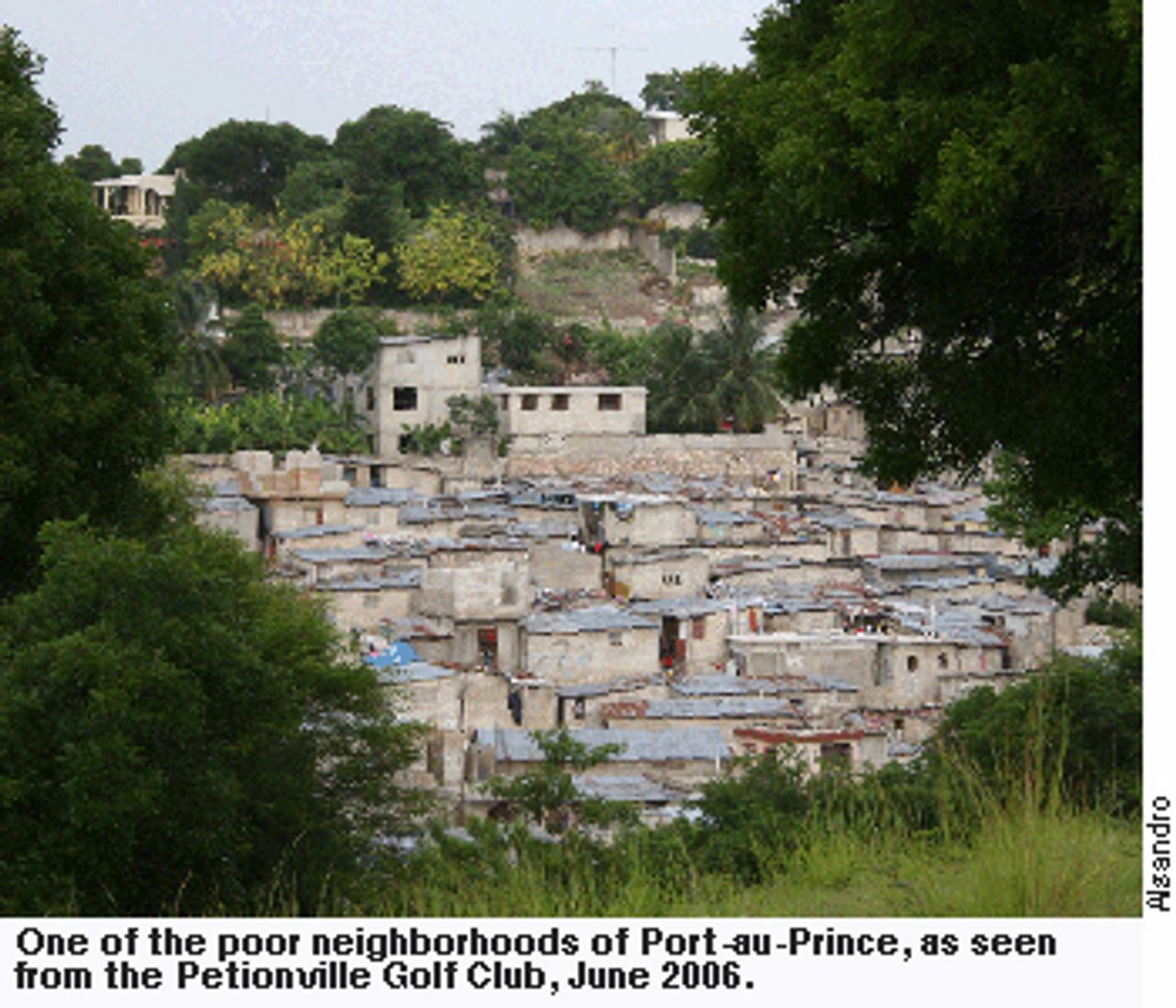

The school, La Promesse (The Promise), was a church-run operation built and owned by Christian preacher Fortin Augustin in a slum below the relatively wealthier hillside neighborhoods of Petionville, a suburb of Haitian capital Port-au-Prince. The school was attended by children from both better-off and very poor families, who struggled to pay upwards of $1,500 in tuition each year.

Residents whose homes were damaged or destroyed in the school collapse told the press that they had long complained that the building was not safe. Eight years ago, the school partially collapsed but was rebuilt. Friday’s collapse was precipitated by construction on the third floor.

One resident commented to the AP, “You can see that some sections just have one iron [reinforcing] bar. That’s not enough to hold it…. I said all the time, one day this is going to fall on my house.”

Fortin Augustin was arrested and charged with involuntary manslaughter on Saturday in connection with the collapse, and officials have suggested he may face life in prison.

Although the negligence committed by Augustin has come under particular scrutiny by officials—many personally eager to avoid shared blame for the disaster—the structural inadequacies and hazardous construction that contributed to the school’s collapse are far from exceptional in Haiti.

During one of several visits to the scene with reporters, Haitian president Rene Preval admitted to the AP that poor construction and the absence of government oversight put many key buildings throughout the country at risk for similar disasters. “It’s not just schools, it’s where people live, it’s churches,” he said.

Preval told the press that Petionville’s previous mayor had moved to halt construction on the school, but that a new mayor allowed it to go forward. Referring to precarious and unplanned construction in the country’s many shantytowns, Preval commented, “There is a code already, but they don’t follow it. What we need is political stability.”

Indeed, the country has been subject to a campaign of political destabilization by the United States for nearly a century, and held at the financial mercy of confederations of imperialist countries such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Haiti has long stood as the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, with fully 80 percent of the population struggling to survive on less than $2 a day.

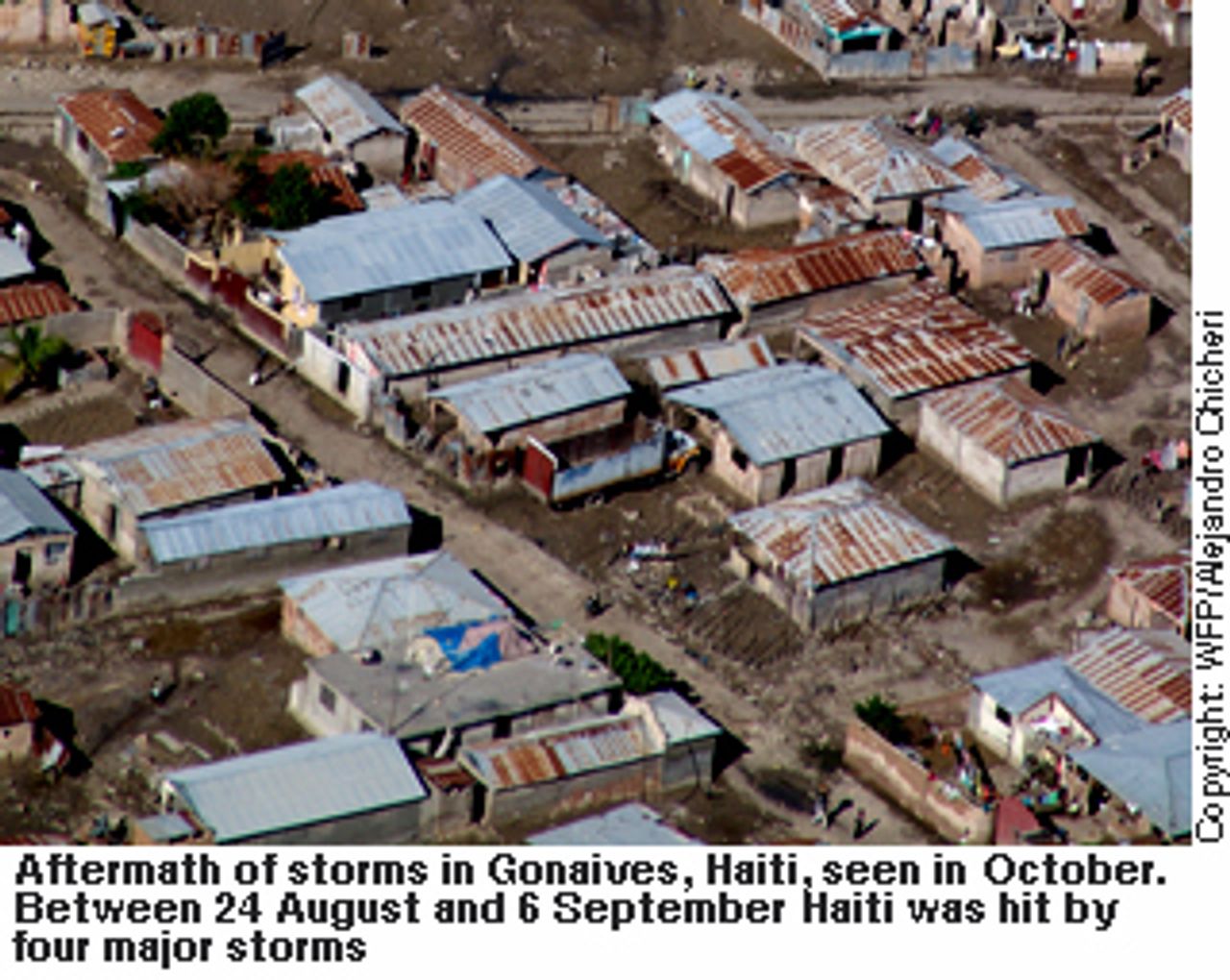

In the past year, wild inflationary spikes in food and fuel exposed millions of Haitians to starvation and prompted massive protests. The food shortages were compounded by a series of devastating storms, which triggered mudslides and flooding. At least 800 people were killed, thousands of homes were destroyed, and 60 percent of the country’s crops were wiped out. (See “Humanitarian crisis worsens in Haiti” )

The scale of the destruction is still making itself felt; some low-lying growing areas remain under water several months later, and farming villages remain cut off due to road washouts. In addition, some 30,000 Haitians are still living in emergency shelters, and many buildings structurally damaged by the storms have not been repaired or razed.