Jørn Utzon, whose name is bound to his greatest, and perhaps one of the world's best-known post-World War II pieces of architecture, the Sydney Opera House, died in his sleep aged 90 on Saturday, November 29.

Jørn Utzon, whose name is bound to his greatest, and perhaps one of the world's best-known post-World War II pieces of architecture, the Sydney Opera House, died in his sleep aged 90 on Saturday, November 29.

Utzon was born on April 9, 1918 in Copenhagen. He entered the Royal Academy of Denmark in 1937 to study architecture, and was influenced by many leading figures of the Modern Movement, the dominant tendency in twentieth century architecture. He worked with Alvar Aalto in Finland and in his travels met Frank Lloyd Wright, Charles Eames and the Finnish architect Eero Saarinen, who was later to be a member of the judging panel that selected Utzon's entry in the design competition for the Sydney Opera House. In Paris he met and held discussions with artist Fernand Leger and architect Le Corbusier.

In 1945 Utzon established his own practice in Copenhagen and in 1952 designed his own house in Hellebaek. Work was scarce, however, and he entered many architectural competitions. In 1957 Utzon was appointed to his most challenging and remarkable commission, the Sydney Opera House. In 1966 he was forced out of the project by the New South Wales state government, leaving his extraordinary work to be finished by others.

Notable later works by Utzon and his two sons, Jan and Kim, include the Bagsvaerd Church near Copenhagen (1968-76), the Kuwait National Assembly (1971-83) and two more of his own houses on the Mediterranean island of Majorca (1971 and 1994), where he spent much of his later life.

Utzon was accorded international recognition late in life, reflecting a growing appreciation of the merit of his Sydney Opera House design. He was awarded the most prestigious architecture award, the Pritzker Prize, in 2003, and in 2007 the Sydney Opera House was declared a World Heritage Site. In the last decade of his life, Utzon and his son Jan collaborated in the refurbishment of the Sydney Opera House.

Australian architect Richard Johnson, who is currently preparing to implement Utzon's design principles, has explained that Utzon saw the building as a "work in progress". He recalled Utzon's comment on the interiors that deviated from his original design: "Every garden has a few weeds but that shouldn't stop you enjoying the garden."

Utzon was very proud of the Utzon Room, the first built interior space in the opera house that he actually designed. A colourful mural designed by the architect and based on C.P.E. Bach's Hamburg Symphony dominates one side of the space opposite a window wall overlooking the water. Gold highlights in Utzon's mural represent explosions of violins. Natural timbers on the floor and walls and the very fine off-form concrete ribbed ceilings complete a fine interior space. The fact that Utzon never returned to see the finished building after 1966 never diminished his deep-going connection with his work.

The Sydney Opera House has posted hundreds of tributes to the Danish architect on its web site. The warmth and appreciation of these tributes is remarkable. Architect Oktay Nayman writes: "As an assistant to Utzon for seven years, through happy times in Sydney and difficult times afterwards, I can hardly express the sorrow I feel for his passing away. Many eloquent things have been said and written about him as a creative genius, and I can attest here that none of them is an exaggeration. To all that, I would like to add only this: his creativity flowed, above all, from the deep humanity in his heart and incorruptible integrity in his mind."

Sydney architect Stephen Malone wrote: "I was a young architecture student present at the protests when Utzon was dismissed, and I remember clearly wandering around the unfinished spaces mesmerised. I have visited the building many times since and on every occasion the experience has been spine tingling, especially the view as you mount the entry stairs—the three sail forms lean towards you, beckoning, inviting you in. Beautifully proportioned, exquisitely scaled. Thank you Jørn Utzon."

Brett Halliwell comments: "I am a subscriber to the Australian Opera as much for the joy of attending Jørn Utzon's magnificent building, as to enjoy the theatrical experience of opera. My partner and I share a love of this building and secretly treat it as ‘ours'; but we're delighted that many millions of other people who visit take it into their hearts too. We always enter our beloved Opera House by promenading up via the sweeping outside stairs, just as Jørn envisioned it. Ascending into the building via the external stairs, rather than via the underground entrance and internal escalator, is our physical way of honouring the genius and vision of Jørn Utzon. Thank you for the wonderful gift of Sydney's Opera House to me, my partner, my city, my country and to mankind."

The Sydney Opera House stands as testament to a deeply humane and generous architect whose motivation was to enhance and enliven the experience of the performing arts, an admirable quest.

Published below is my architectural review of the Sydney Opera House, originally posted on the World Socialist Web Site on December 4, 1998.

* * *

The Sydney Opera House:

How government policy imperiled an architectural masterpiece

On the 25th anniversary of the Sydney Opera House, the New South Wales state Labor government has approached Jørn Utzon, the building's original architect, to oversee planned renovations. Thirty-two years ago, thanks to bureaucratic interference, Utzon was forced to end his work on the partially completed project. Since his departure from Australia on April 28, 1966, the architect, now 80 years old, has never returned to see the Opera House—one of the great architectural masterpieces of this century.

In a recent letter, state Labor Premier Bob Carr offered Utzon final say on all design principles in the 10-year, $66 million renovations. The letter refers to the need to upgrade the acoustics of the two main theatres. It is perhaps more than coincidental that in the leadup to the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games, with a stylised opera house in the Games' official logo, the government has attempted this essentially symbolic reconciliation. The relatively small budget for the renovations reveals that the government has no intention of reconstructing Utzon's original plans for the interiors, which were aborted after his removal.

Utzon won the design competition for the Opera House in January 1957. Over the next nine years he produced some extraordinary architecture working under unusual circumstances of wide artistic freedom and extensive funding, derived from the proceeds of a special state lottery.

Utzon won the design competition for the Opera House in January 1957. Over the next nine years he produced some extraordinary architecture working under unusual circumstances of wide artistic freedom and extensive funding, derived from the proceeds of a special state lottery.

In 1965, however, the conservative Liberal-Country Party won the state elections, having campaigned against the cost of the opera house construction and the indeterminate finishing date. Immediately on taking office, the conservatives set out to rein in the architect and began withholding fee payments. By 1966 Utzon, who realised that his continued work would be impossibly compromised, resigned. The main structure, including the magnificent shells, had just been completed.

Fortunately this work could not be undone, but Utzon's interior designs were scrapped and the government introduced major changes to the designated functions of the main theatres. The new design architect, Peter Hall, in defiance of many of his contemporaries who black-banned the architectural work, accepted the new regime and completed the interiors. Any visitor to the Opera House today is inevitably disappointed with the stunning discrepancy between the wonderful exterior and the pedestrian interiors.

Ironically, the removal of Utzon made matters worse. At the time of his sacking, Utzon had worked for nine years, with the project costing $22 million. The new architects took another seven years to complete the building in 1973, at a final cost of $102 million. Had Utzon's designs been completed, the finishing date would have been 1968.

The Opera House graces Bennelong Point, once the site of a government-owned tram and bus depot, and the original location of Fort Macquarie, built in 1821. Surrounded on three sides by the waters of the harbour and adjacent to the arched Sydney Harbour Bridge, its beauty stands in stark contrast to the mundane city office blocks and tourist hotels of downtown Sydney.

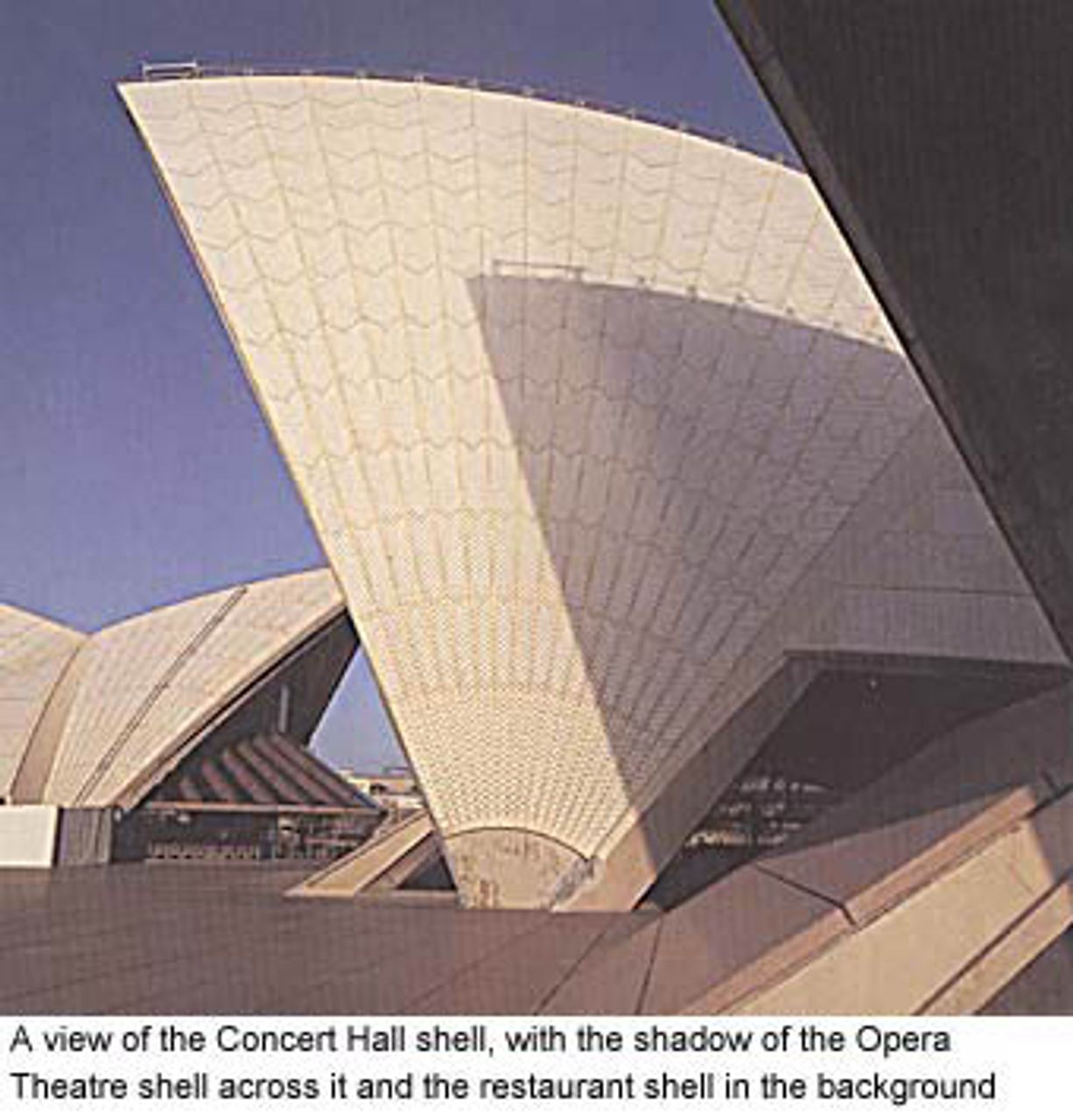

The structure consists of a massive concrete podium extending on three sides beyond the land so that it appears as though the whole building is sitting on the water. The podium contains the service areas, dressing and rehearsal rooms, minor theatres and box office. On top of the podium sit three sets of concrete shells. The smallest houses a restaurant. The two largest, which are angled off-parallel to each other, house the two major theatres. The main concert hall seats 2,690 and the smaller Opera Theatre seats 1,547. The shells are clad with small white tiles, some reflective and some matte.

The result is a dynamic sculpture that reflects and contributes to the ever-changing interplay of light, water, ferries, yachts and other harbour traffic.

There is no distinction between wall and roof, as one becomes the other. The play of light on the shells creates the appearance of a building that is alive and moving. The whiteness of the shells simplifies the form and dramatically increases its profile. The small restaurant shells counterbalance their asymmetrical larger partners in a pleasing composition. The silhouette is always dramatic, resembling nautilus shells inside each other.

How Utzon won the international competition

The decision in 1955 to hold an international architectural competition to build a new performing arts centre in Sydney was the confluence of the efforts of the European-trained and popular head of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Eugene Goossens, and Joseph Cahill, Labor premier of New South Wales. Goossens had transformed the musical scene in Sydney since his appointment in 1947 and won Cahill's agreement to build an opera house.

The international competition attracted great interest from architects around the world. Over 234 designs were submitted. The judging panel was made up of two Australians; Professor Ashworth, head of architecture at the University of Sydney and Cobden Parkes, the New South Wales government architect; and two overseas architects, Professor Leslie Martin from Cambridge University in England and Eero Saarinen from Michigan in the US.

Utzon's competition entry was technically incorrect, as he had not strictly adhered to all the rules. Saarinen arrived late for the beginning of the judging. He asked to see the designs that the other judges had put in the discarded pile. On seeing the schematic sketches of soaring free-form white shells among the rejected designs, Saarinen immediately began convincing the other judges that this had to be the winner, even if it broke some of the competition rules. Saarinen explained his conception. "Really what is great architecture? It's not only how well it works...it's a quality beyond that. It's how much does it inspire man." [1]

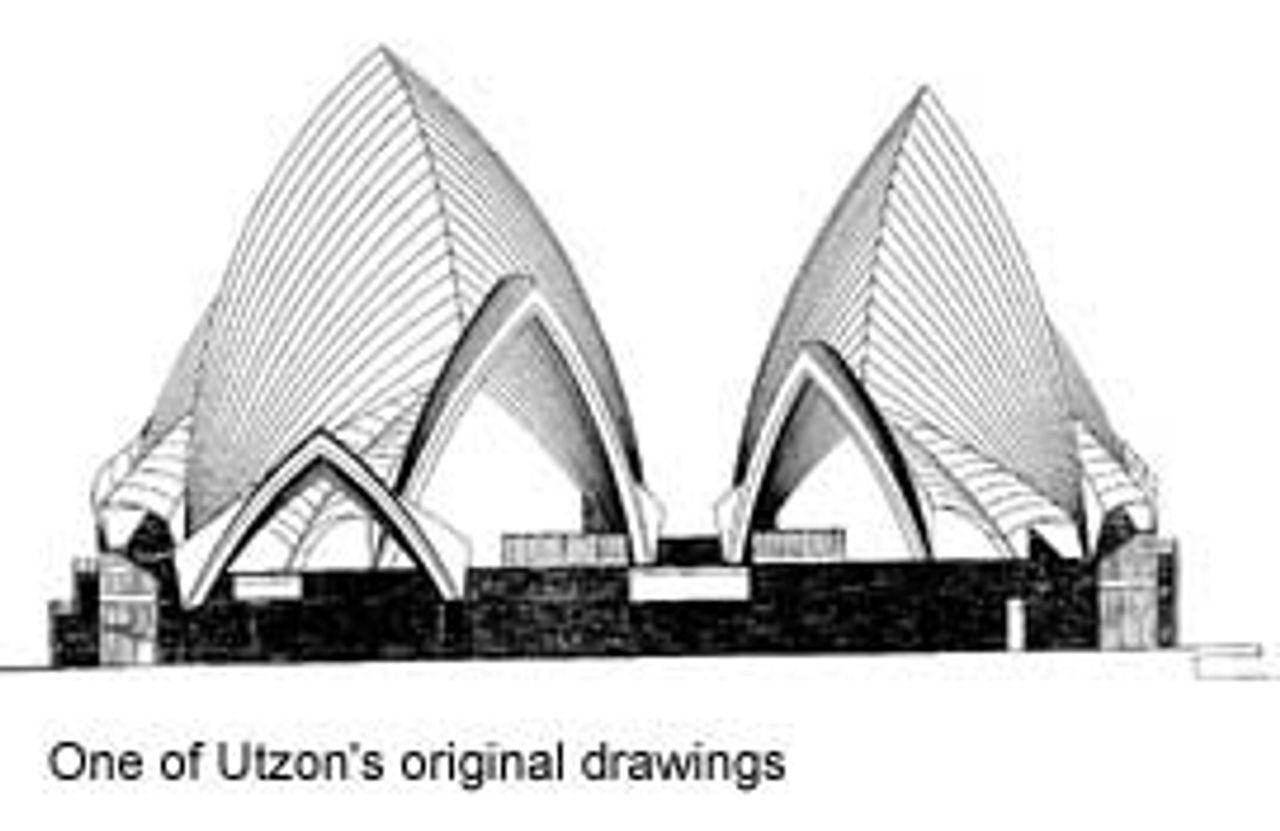

Utzon's design was simple and straightforward. His concept was based on overcoming differing height requirements in the theatres. Traditionally the stage tower, with enough vertical height to take scenery and sets hoisted above the stage, dominated the exterior massing of opera houses. Roofs over audience seating were usually lower and the foyers lower again. Utzon resolved this difficulty in a unique manner by proposing three sets of shells, increasing in size and nestled inside each other. He then suggested a procession up the stepped podium that would reveal nothing to those arriving but the shells, the sky and the water. All the functions were to be housed in the podium below. In this procession the audience were to be taken to another world, separate from their daily lives, ready to immerse themselves in the performance.

Utzon's design was simple and straightforward. His concept was based on overcoming differing height requirements in the theatres. Traditionally the stage tower, with enough vertical height to take scenery and sets hoisted above the stage, dominated the exterior massing of opera houses. Roofs over audience seating were usually lower and the foyers lower again. Utzon resolved this difficulty in a unique manner by proposing three sets of shells, increasing in size and nestled inside each other. He then suggested a procession up the stepped podium that would reveal nothing to those arriving but the shells, the sky and the water. All the functions were to be housed in the podium below. In this procession the audience were to be taken to another world, separate from their daily lives, ready to immerse themselves in the performance.

Utzon was born in 1918 in Copenhagen, Denmark. His father was an English-educated naval architect. Utzon studied architecture in Copenhagen and during the war joined a Danish resistance group in Sweden called Danforce. After the war he traveled extensively and either worked for, met or heard lectures by the greatest architects of the modern movement, including Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright. Utzon learnt from French sculptor Henri Laurens and worked with architects Gunnar Asplund and Paul Hendquist in Stockholm. In 1952 Utzon entered a partnership with Erik Andersson and his brother who were based in Sweden. Most of their projects were large-scale residential developments.

Utzon's attitude to architecture was expressed in a reference to Louis Kahn, the renowned American architect. "Kahn describes art like this. On one side of the line is truth—engineering, facts, mathematics, anything like that. On the other are human aspirations, dreams and feelings. Art is the meeting on the line of truth and human aspirations. In art, the one is meaningless without the other."[2]

This outlook was embodied in his design for the Opera House. Utzon was attempting to address the basic functional aspects of the building but with a poetic response to the environment of Sydney Harbour. Thus he differentiated himself from the strict modernist nostrum that form had to follow function. At the same time there was a rational underpinning to every element of the design.

The construction of the concrete shells was originally intended to utilise concrete membrane techniques with thin reinforced concrete of 75-100 millimetres (3-4 inches) thickness. This proved to be impossible on such large free-form shapes as originally planned. After three years of intense work with the structural engineering firm Ove Arup, trying to solve the structure of the shells, Utzon came up with the stunningly simple yet graceful solution of making all the shells portions of the same-sized sphere. This allowed prefabrication of the concrete rib elements all with the same radius. As the shells got bigger the next-sized elements were added on.

Utzon's conception of "additive architecture" was to create objects of quality and beauty using mass-produced industrialised processes. It also became much more straightforward to do the necessary structural computations in a period where the use of computers was in its infancy. The simplicity underpinning this rationality of construction impacts on the beauty of the finished form.

Discussing the competition for the Opera House, Utzon said: "We didn't dream of winning it. We were inspired to do it. A certain amount of your time you want to devote to clean architecture—without clients or anything like that. That's one of the symptoms of architecture. That's when the architect is closest to the pure artist." [3]

Creative inspiration versus commercial pressure

In this statement Utzon summarises one of the central problems that emerged during the construction. Originally the government appointed the Opera House Executive Committee to liaise with Utzon and to pay his fees. This committee was made up of representatives of the performing arts and architects who were supportive of his radical design. Utzon's modus operandi was to work with models and mockups. In architectural terms this allowed experimentation with forms and materials through trial and error. The cost of the models and tests was borne by the Executive Committee.

In commercial architecture the design is finalised and the drawings completed before builders submit competitive tenders to build. The client or building developer knows on the day construction begins how much it will cost, the anticipated rental or re-sale value of the building, and therefore how much profit will be realised. These were not the considerations of Utzon and the Executive Committee. Some of those who worked in Utzon's office at the time explained that the sole motivation was to achieve perfection in every aspect of the design. To work under such conditions was obviously a fulfilling and memorable experience.

After construction commenced, the design was still being developed. This created some problems on site where the builders' progress was frustrated by regular changes in drawings. It was also difficult to provide accurate costings.

In May 1965 the Labor government was replaced with the Askin Liberal-Country Party government. Davis Hughes, a leading member of the Country Party, was appointed Minister for Public Works. Premier Robin Askin had campaigned against the cost of the project and Hughes had campaigned for money to be spent on roads and dams, not "extravagances" for Sydneysiders.

The payment of Utzon's fees was transferred from the Executive Committee to the Public Works Department in July 1965. Immediately the government withheld fees to bring pressure to bear on Utzon.

In a letter to Hughes on 12 July 1965, Utzon attempted to explain the design process underway. "It was mutually agreed with the client that, every time a better solution was evolved on one point or another, it was necessary to incorporate the better solution. I have not compromised with either my previous client or the consultants in my search for perfection. This is what separates this building from any other—that it is being perfected at the same time as it is being built."

This impassioned argument fell on deaf ears. Hughes' agenda was to curtail Utzon's work methods and introduce a commercial client-architect relationship. The issue that brought matters to a head was the refusal of Hughes and the Public Works Department to authorise money for the building of plywood mock-ups of an ingenious new ceiling construction for the main halls. Unable to test his new method with real materials, Utzon was prevented from developing his concepts for the interiors, and the building works stagnated.

Another aspect of the difficulties that arose was government vacillation on the types of performances to be held in the building. The government had launched the project to develop the performing arts. Yet because these arts were in a fledgling state by international standards there was no clear and definite conception of what was required. Utzon acted on the original brief to build a small theatre of 1,200 for drama and a major multi-purpose theatre to seat 3,000 that could accommodate both opera and symphony orchestras. Traditionally, opera and orchestra do not work well together, as opera requires a smaller more intimate space, ideally with around 1,500 seats, accompanied by all the ancillary features, including orchestra pit, stage, set storage and a reverberation time of around 1.2 seconds. An orchestral hall, however, requires a much more open stage, a reverberation time of 2.1 seconds and many more seats.

After Utzon's departure the government decided that the opera and orchestral functions should be separated into two theatres. This decision was prompted by many factors, not least of which was the need for more seating to render the Australian Broadcasting Commission orchestra economically viable. In addition, opera lobby was less powerful at that time.

A huge outcry of opposition greeted the announcement of Utzon's departure. Leading architects from around the world wrote to the government in protest. Architects, students and many others were outraged. Placards at demonstrations held to protest Utzon's removal read "Griffin, Now Utzon". This was a reference to the shameful and bureaucratic treatment, half a century earlier, of American architects Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin, who had won the competition to design the national capital, Canberra. While architects in New South Wales and throughout the country were bitterly divided for decades over Utzon's treatment, those seeking the patronage of the powerful Public Works Department cooperated with the government interference.

"Unseen Utzon," a recent exhibition organised by Phillip Nobis, an architecture student, made Utzon's original designs available to a wider audience. What characterises Utzon's treatment of the interiors was his use of colour and fantastic shapes. The ceilings of the main theatres were to be a staggered flow of curved sections of self-supporting plywood beams, all built to the same radius. Like the outside shell, there was a coherent and easily fabricated rationale behind a dynamic, exciting effect. Utzon likened it to a walnut, in which the rugged kernel snuggles into the smooth shell. In fact, as the ceilings were self-supporting, their exterior was to be exposed. Bright gold and red colourings were to be used to enliven the interiors in contrast to the white simplicity of the outside shells.

Notwithstanding the appalling government interference, Utzon's opera house remains one of the finest examples of modern architecture, a work of great artistic merit.

Notes:

[1] The Edge of the Possible, Film Art Doco Pty Ltd, directed by Daryl Dellora

[2] Opera House Act One, by David Messent, (Sydney, 1997) p. 103

[3] Ibid. p. 128