This is the fourth and final in a series of articles on the recent Vancouver International Film Festival (September 28-October 13).

The flood of documentary films—good, bad and indifferent—about the war in Iraq, the Bush administration, terrorism, oil, religious fundamentalism and related matters continues unabated.

In addition to Iraq in Fragments (James Longley), about which we have already commented, the Vancouver festival screened a number of other works, including A Crude Awakening: The Oil Crash (Basil Gelpke, Ray McCormack, Reto Caduff); The Root of All Evil? (Russell Barnes); American Zeitgeist: Crisis and Conscience in an Age of Terror (Rob McCann); Iraq for Sale: The War Profiteers (Robert Greenwald); Shadow Company (Nick Bicanic, Jason Bourque); My Country, My Country (Laura Poitras); Our Own Private Bin Laden (Samira Goetschel); The Epic of Black Gold (Jean-Pierre Beaurenaut, Yves Billon); Hamburg Lectures (Romuald Karmakar); and The Smell of Paradise (Mariusz Pilis, Marcin Mamon).

In addition, there were several documentary films shown about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: Encounter Point (Ronit Avni, Julia Bacha), Raised to Be Heroes (Jack Silberman) and More Than 1000 Words (Solo Avital).

Speaking broadly, this stream of works about current global problems is welcome. It can be considered, in part at least, a response to the general silence of the American film industry especially about virtually anything of significance to the population. Mass distrust, skepticism and restiveness cannot be eternally contained. Alternatives to both the official media and the official entertainment industry have sprung up.

Numerous filmmakers are turning their attention to the objective world of politics and economics. They are apparently not paralyzed by the tedious argument that because all filmmaking choices are ‘value-laden,’ therefore no even relatively objective account of things is possible. Events are pressing, and, quite rightly, documentary filmmakers, brushing by the academic “leftist” purveyors of such arguments, have begun to do their work.

This doesn’t mean, obviously, that the problems have disappeared. In the end, the majority of nonfiction films reveal some of the same difficulties as many fiction films: a weak grasp of more complex social realities, a tendency to remain on the surface, the lack of profound artistic intensity and commitment.

Much of what was progressive in cinema verité and other nonfiction schools (Direct Cinema, etc.) of the late 1950s and 1960s—spontaneity and mobility, a hostility to the spoon-feeding (lecturing) style of the Stalinist or Labourite school of social documentary making—wore thin quite some time ago. In the name of opposing heavy-handedness and didacticism, a worthy enough goal in itself, the baby was long ago thrown out with the bathwater. In any event, the documentary practitioners, the pioneers of cinema verité, of several decades ago had a considerably greater grasp of social life than the present generation of filmmakers.

We have often been confronted, until recently at least, on the one hand, with documentaries that are simply heaps of images without a guiding principle; or, on the other, works in which the filmmaker has become the principal subject. The latter, whether explorations of family history, sexual identity or personal obsessions, are mostly, although not all, unfortunate. The emergence of the new social documentary presents new challenges.

The nonfiction filmmaker finds him or herself face to face with a complex, volatile, often brutal world without sufficient understanding of its inner laws and processes. And it is an unworthy prejudice, too common at present, to believe that spontaneity and knowledge are mutually exclusive. On the contrary, only the firmest grounding in reality gives the filmmaker the freedom to move with confidence and elegance, and not fall prey to the arbitrary and tangential.

One of the obstacles that has to be overcome, not a small matter, is the assumption held by virtually all the documentary makers that the present social order is eternal. The consequences of the collapse of the Stalinist regimes and the campaign over the ‘death of socialism’ have not yet been surmounted. A generation nourished (or malnourished) in the intellectual atmosphere of the 1990s continues to have difficulties.

The promises of 1989-91, of a new golden age of peace and prosperity, of the ‘end of history’ and so on, have given way to unending war, vast and chronic social polarization and threats of police-state dictatorship. The understanding of the artists, however, lags far, far behind.

To align one’s thinking closer to reality can be a painful process. It’s certainly not for everyone. Nonetheless, a section of the filmmakers needs to take this step, for the sake of its audience and for its own sake. To be blunt, one cannot get very far, artistically or any other way, when considering various political and social circumstances if the elimination of their ultimate source, the capitalist system, is excluded as a possibility.

Many of the contradictions and implausibilities of nonfiction film flow from the perceived need to go only so far and no farther in the social analysis. More than one documentary exposé launches into its subject and presents the most damning statistics, examples or accounts, tending to show the unbearable consequences of present-day economic and social organization for this or that country or social group, only to end up proposing some miserable reformist pipe dream as a solution (placing pressure on the IMF, appealing to Congress or parliament, putting teeth into the UN, etc.).

The first prerequisite for a genuine advance in documentary filmmaking, therefore, is the emergence of an openly anti-capitalist tendency, a tendency which traces problems to their historical and social roots in the foundation of society. This is not at all the same as a superficial radicalism, which can point to any number of ills, but for whom social life is a series of inevitable defeats for the outnumbered and overpowered “underdog.” History stands still for such individuals; for them, the “little people,” organically incapable of advancing their own interests, are engaged, like Sisyphus, in a timeless and perpetually losing battle. We’ve had enough of this, particularly when it takes on a maudlin coloring; better the “cruel thoroughness” of self-criticism that Marx advised.

The “firmest grounding in reality” today means taking conscious and studied note of historical conditions—a globally-integrated economic, social and cultural life and a social force, a vastly expanded working class—that make possible (and rational) a transformation in our social circumstances. Some recognition of these facts will have to sink in for the present artistic situation to markedly change.

Oil and social life

Two of the films in Vancouver dealt with the question of oil as a social phenomenon: The Epic of Black Gold and A Crude Awakening: The Oil Crash. The first is an often fascinating account of the history of oil as a source of conflict since 1859, when “Colonel” Edwin Drake established the first successful well in Titusville, Pennsylvania. The French-made documentary briefly examines the origins of Standard Oil, founded by John D. Rockefeller, as well as the other majors, including Shell and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (predecessor of British Petroleum), whose employees in 1908 made the first commercially significant find in the Middle East, in Iran.

The Epic of Black Gold discusses the parallel rise of the oil and automobile industries, and the vast demand for petroleum products created by modern warfare. It looks at the rise of “Oil Nationalism” in countries such as Mexico, whose Cardenas regime nationalized the oil industry in 1938, Venezuela and Iran, where the US financed a coup in 1953 against the government of Mohammed Mossadegh after he attempted to nationalize foreign oil interests.

The film argues that the desire of the German and Japanese ruling elites for access to oil supplies was a driving force in the outbreak of the Second World War. A historian maintains that US access to superior oil products, particularly aviation fuel, was a determining factor in the war’s outcome.

The famous encounter between Franklin D. Roosevelt and Saudi King Abdelazziz ibn Saud on board a US Navy cruiser in 1944 (caught by a newsreel camera) guaranteed oil supplies to the US in exchange for American support for and protection of the reactionary Saudi royal family and its regime.

The film continues on, with some remarkable footage, presenting the Suez crisis of 1956, the beginnings of OPEC, the consequences of the Evian agreement ending the French-Algerian war, the rise of figures like Gaddafi in Libya and Hussein in Iraq. It argues that the fourfold jump in oil prices following the Yom Kippur war in 1973, which precipitated the “first oil crisis,” had less to do with a newfound interest in the Palestinian cause on the part of OPEC’s members than a longstanding determination by the Saudis and others to raise prices.

Jean-Pierre Beaurenaut and Yves Billon’s film proceeds to the two Gulf wars and the eventual overthrow of the Hussein regime by the US. Sheikh Ahmed Zaki Yamani, the former Saudi oil minister and a major figure in OPEC for years, argues that the drive to control oil supplies, not “democracy,” was the principal motive for the American invasion in 2003.

The final section, “Oil Depletion,” discusses the declining reserves of the non-renewable resource. It paints a picture of soaring Chinese demand in particular and the American population’s “careless consuming of energy” as central difficulties. In the film’s final note, a geologist suggests that, faced with the declining availability of oil, “we’re moving from the bronze age back to the stone age.”

This note is picked up and amplified in A Crude Awakening, a film dedicated to the issue of peak oil, i.e., the peak and eventual decline of the planet’s oil production. (In fact, the two films share some of the same talking heads.) After discussing the science of oil’s creation, the film weighs in on the fossil fuel’s centrality to the world economy. Moreover, in the somewhat cavalier fashion of the first film, it argues that “oil starts wars.”

Various experts warn about the political and economic implications of dwindling oil reserves. “More and more oil is going to come from less and less stable places,” someone notes. The claim is made that OPEC members exaggerate their oil reserves. “The numbers don’t add up,” one expert alleges. The oil-producing countries have an interest in maintaining a high figure on their reserves, it is argued, because this makes it possible for them to increase production quotas.

The theories of M.K. Hubbert, a geophysicist who worked for Shell Oil, are introduced. In 1956, Hubbert argued that oil production in the continental US would peak around 1970 and that world production would reach its height and begin to decline within “about half a century.”

One of the talking heads in both films is Matt Simmons, an energy-policy advisor to the 2000 Bush-Cheney campaign, the founder of an investment bank that counts Halliburton among its clients and author of Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy. Simmons claims that the Saudis are concealing the truth about their oil reserves and that the world is fairly rapidly running out of oil. He argues that peak oil production has been or is about to be reached and that in 5 or 10 years the world will be producing less oil than it does today.

Whatever the scientific facts may be, and considerable controversy surrounds the theory, there is little question but that ‘peak oil’ inevitably becomes an element in various political agendas. For Simmons, who regularly speaks to George W. Bush, and the Republicans in Congress, the oil crisis means immediately opening up the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling. Beyond that, although this is not Simmons’s stated view, since oil is so vital to America’s “national interest,” doesn’t its threatened shortage require the US to establish more direct control (military or otherwise) of these soon to be depleted reserves?

The response of the makers of A Crude Awakening is positively Malthusian. One of their talking heads argues that automobiles and air travel will only be available in the future to the super-elite. “Will my grandchildren ever ride in an airplane?” The film essentially argues that the planet has too large a population, especially in the absence of easy access to oil. “How many people can the world support without fossil fuels? Perhaps 1 to 1.5 billion.” The horrifying implications of this startling remark are never worked out.

In their doomsday scenario, the filmmakers and their talking heads envision human society going back to a previous century. The present lifestyle is “impossible to maintain.” Once more, the population is blamed, for its “insatiable demands” and its addiction to “gas guzzlers.” They predict the end of “hydrocarbon man,” while suggesting that “homo sapiens will carry on living in some different, simpler way.”

Again, the film’s makers and their various experts (including extreme right-wing Republican Congressman Roscoe Bartlett of Maryland) share one common assumption: that a world free from the domination of the oil conglomerates and their profit drive and the budget constraints of competing national capitalist states (for example, it is argued at one point that the chief barrier to solar energy is “cost”), in which human society might rationally work on and develop alternative energy supplies, is inconceivable.

Islamic fundamentalism

Our Own Private Bin Laden is an odd but occasionally revealing film, directed by Samira Goetschel, the daughter of an Iranian executed by the Khomeini regime after the overthrow of the Shah. An émigré, Goetschel’s stated purpose is to get to the bottom of Islamic radicalism, to figure out how this movement rose to prominence.

To the director’s credit, she goes after some major figures. While none of this is terribly new, her interviews with former National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, former CIA director Stansfield Turner, former CIA operative Milton Bearden, former Pakistani prime minister Benazir Bhutto, onetime investigator for the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee Jack Blum and others reveal once again the filthy nature of US operations in Afghanistan in the 1970s and 1980s.

In her conversation with a testy Brzezinski, Goetschel refers to his widely publicized remark that he has no regrets about stirring up Islamic fundamentalism in Central Asia as part of the struggle to undermine the USSR. “Do you stand by your statement?” she asks. Essentially, Brzezinski does, arguing that the Soviet Union, in any case, was to blame for pulverizing Afghanistan. Compared to the collapse of the USSR, the Taliban were unimportant, he goes on. The interviewer returns to the same theme, “Was it justified to use Afghan lives in the fight for US interests?” Brzezinski rejects the “dramatically conspiratorial terms” of the question.

Light is also shed in the film on the reactionary character and ambitions of Osama Bin Laden and the social layer for whom he speaks, or fights. Speaking of Bin Laden’s thinking, one of the Arab interviewees explains: “We [the Arab elite] produce the oil, they [the Western oil companies and regimes] get the benefit. [In the future] Oil will be sold, but on our terms.” In other words, this faction of the Saudi and Arab bourgeoisie is struggling, with terror as its weapon, to strike a better bargain with imperialism.

My Country, My Country is a rather tame portrayal of the present situation in Iraq, through the portrait of Dr. Riyadh, a respected Sunni medical doctor in Baghdad, and his family. Riyadh comes across as a personally honorable individual, and the film is not devoid of striking images, but the director, Laura Poitras, makes relatively little of the devastating impact of the American occupation.

The film proceeds in confusing fits and starts, without thoroughly examining any single phenomenon. We see indications of the chaos and mayhem, such as the lack of electricity. Bombings and shootings are referred to, which Dr. Riyadh bitterly refers to as “the fruits of democracy,” but no coherent picture emerges. The quasi-farcical election process continues, firmly under the American thumb, in which the doctor intends to stand as a candidate. In the end, his party opts for a boycott of the election, against his objections.

The director’s attitude toward the colonial-style occupation is never made clear. “It’s not all bad,” says one US official. Are we supposed to think so too? The filmmaker travels to northern Iraq and meets grateful Kurds. Perhaps it’s not all bad then. And the election at gunpoint, in which parties calling for US withdrawal were forbidden to run, are we supposed to take this seriously? All in all, the films seems muddy and weak.

One of the most passive efforts, almost to the point of turning into an apology for its subject, is Shadow Company, by Canadians Nick Bicanic and Jason Bourque. The film is a look at the rapidly expanding role of mercenaries and “private military companies” (PMCs), such as Blackwater Security in Iraq. Taking the deaths of four Blackwater private security contractors in Fallujah in 2004 as its starting point, the film sets out to explore this new world of “privatized” warfare.

Shadow Company reminds us of some remarkable facts, for example, the presence in Iraq of 20,000 mercenaries, more than the total of non-US coalition troops and one for every seven American soldiers. It traces the origins of the modern mercenary to the independence of Zimbabwe, formerly Rhodesia, in 1980, and the exodus of many white Rhodesian soldiers to South Africa. Executive Outcomes was one of the first of the new mercenary outfits that emerged, a private army for sale.

In more recent years, the events of September 11 provided a boost to the private security business, which experienced a 50 percent growth in the following year. An estimated 50 firms currently operate, with $100 billion in annual revenues.

The diary of a mercenary in Iraq forms part of the narration, and presumably we are not intended to approve of some of the backward and quasi-racist comments. Nor are we supposed to admire the “cowboy” methods of these types, including indiscriminate shooting and violence.

Nonetheless, the filmmakers provide a platform for private security officials and assorted mercenaries to make their case. The experience of Sierra Leone, where the National Provisional Ruling Council in 1995 hired several hundred mercenaries from Executive Outcomes “to clear out the diamond area,” is held up as a model of the positive role mercenaries can play, and no one is brought forward to contradict this. Indeed not a single African or Arab voice can be heard in the entire film. The strongest comment comes from a retired Canadian army officer, who refers to the privatized military activity as “imperialism.”

Shadow Company ends with a list of mercenaries who have died “in action”! To repeat, this is passivity that borders on politically criminal negligence.

Against religion

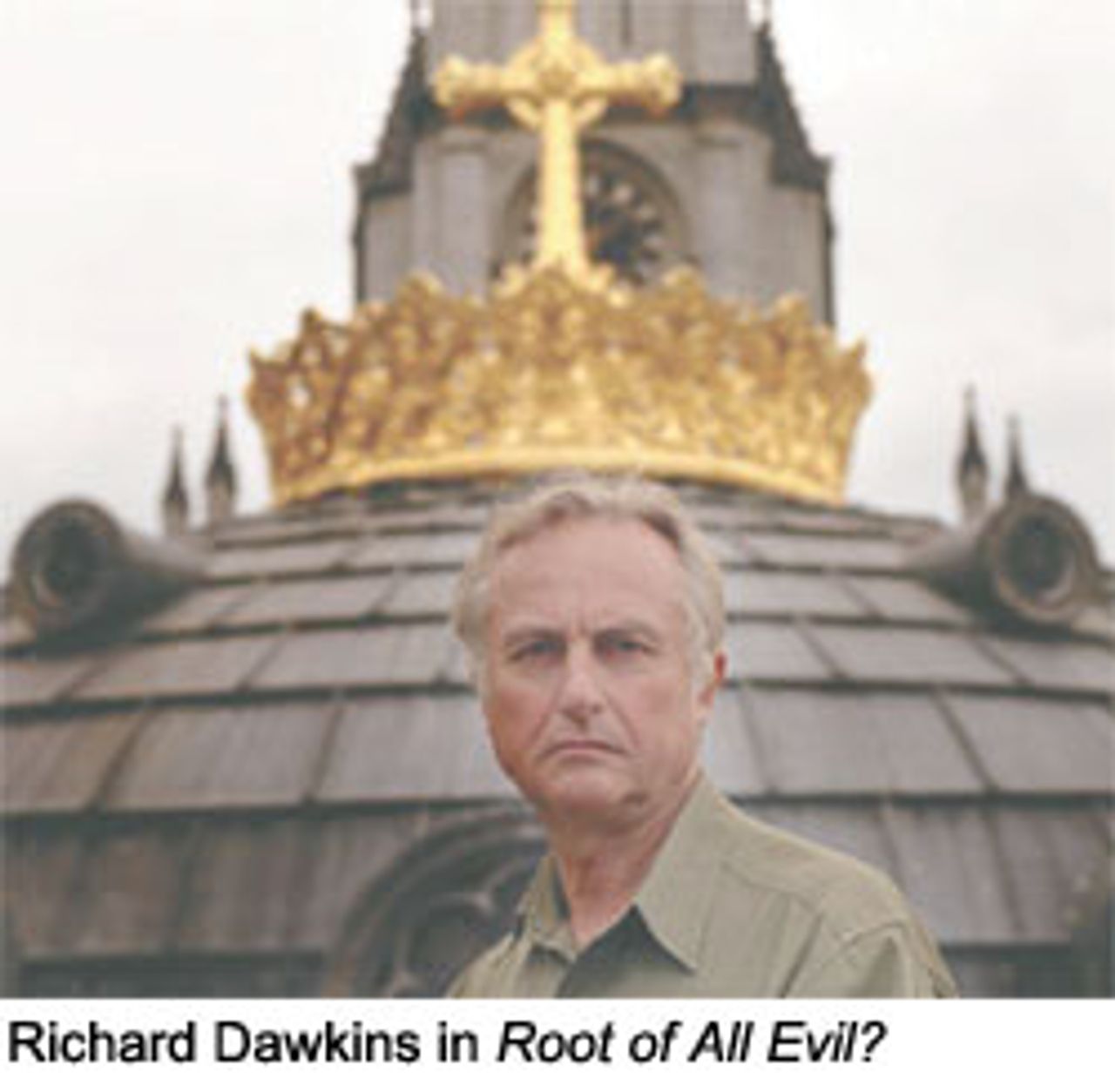

Richard Dawkins, the evolutionary biologist, is the writer and presenter of Root of All Evil? (the title was not Dawkins’s choice), a two-part series about organized religion broadcast on Britain’s Channel Four in January 2006. Dawkins argues that religious faith (“the suspension of critical faculties”) is not a way to grasp the world, but rather stands in fundamental opposition to modern science and the scientific method. “The time has come for people of reason to say: enough is enough,” he states. “Religious faith discourages independent thought, it’s divisive, and it’s dangerous.”

Religion, the scientist argues, depends on unsolved mystery, and is a hangover of early humanity’s ignorance and weakness in relation to nature. He contrasts the history of the Catholic doctrine of Mary’s assumption (that Christ’s mother ascended to heaven body and soul intact), which Catholic believers are simply to take on the pope’s word for it, with the scientist’s approach, based on comparing and evaluating evidence. He tells the story from his undergraduate years of a visiting scholar disproving a major hypothesis of Dawkins’s professor, and the latter greeting the refutation with, “My dear fellow, I wish to thank you, I have been wrong these 15 years.”

Dawkins ventures into the territory of American evangelicals, visiting a church in Colorado Springs, Colorado, presided over by Ted Haggard, chairman of the National Association of Evangelicals (who boasts of a weekly call with George W. Bush). He mutters that religion here is “free enterprise,” saving souls and making money. Dawkins compares the fundamentalist service to a Nuremberg rally. In an increasingly acrimonious conversation with Haggard, the biologist demonstrates that the preacher knows nothing about evolutionary theory. In the end, Dawkins and his film crew are thrown off the church property and threatened with legal action.

Dawkins comes across as an admirable figure, and one can only cheer as he delivers blows to religious bigotry, mysticism and unreason, which generally go uncriticized in the media and contemporary cinema. His limitations emerge when his brand of materialism comes into contact with profound historical and social processes, and in particular problems of mass consciousness.

Dawkins is simply nonplussed, for example, by the continuing hold of religion on sections of the American population. Religion contradicts reason, therefore any thinking person should reject it, he argues. To grasp the role that religion plays in American society one would have to make a study of the country’s entire history and evolution, but perhaps equally importantly, one would need some deep grasp of the specific contemporary political and moral vacuum in which fundamentalism has flourished—the degeneration of liberalism, the decay of the trade unions, in fact, the general abandonment of the population by all those organizations that once claimed to champion the cause of social reform. When no one, absolutely no one comes to a person’s aid, he or she is more likely to call on Jesus.

Absent this understanding, quite mistaken political conclusions can be drawn. Dawkins visits a group of beleaguered “humanists,” who are apparently convinced they are a tiny minority of the enlightened in a sea of ignorance and brutishness.

“Refuseniks”

In Israel, some 1,600 soldiers have refused to take part in military operations in the occupied territories and Gaza Strip. Numerous so-called “refuseniks” decided not to take part in the recent invasion of Lebanon. This movement is the subject of Raised to Be Heroes, directed by Jack Silberman. The film also follows the case of Matan Kaminer and four other high school students who are refusing to sign up for the military because they believe its actions are wrong.

The film contains numerous moving and revealing moments. The policies of the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) are denounced in terms unheard of in the American media. Col. (Res.) Yoel Piterberg, leader of a Black Hawk helicopter squadron, explains, “For me it’s a crime, it’s a big crime, international by law and moral by myself, my heart, and I don’t want to be part of it.”

Another soldier tells of taking part in the torture and eventual death of a 14-year-old Palestinian boy during the Intifada. “We tortured him all night till he died.” The same man raises the example of the Warsaw Ghetto. The plight of the Palestinians reminded him of “the situation of the Jews.” The German troops “saw them as terrorists,” not human beings, but animals. “The analogy is really clear.”

Later, the same soldier tells the camera, “I was watching a 14-year-old boy die, and I did nothing. Am I different [from the Nazis]? Would I have taken part in worse activities?”

None of the “refuseniks,” at least in the course of this film, challenge the fundamental premises of Zionism. One claims, in fact, that Zionism “has nothing to do with what we’re doing to the Palestinians.” In fact, what the Israeli elite and army are “doing to the Palestinians” is the inevitable and fatal logic of Zionism. The position of the refuseniks, courageous as they are, that the activities of the IDF are “war crimes” in the West Bank and Gaza (and perhaps Lebanon), but legitimate elsewhere, is ultimately untenable.

* * *

The Toronto and Vancouver film festivals this year registered a change in the global social atmosphere. With all its limitations, this change speaks to a broader radicalization occurring under conditions of war, the wholesale assault on democratic rights and the deterioration of living conditions for wide layers of the population.

The WSWS will follow this process. We also encourage filmmakers, writers, performers and critics to send us their thoughts and contribute to this discussion.

Concluded